In the fall of 2008, Boston’s Modern Theatre looked anything but modern. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the landmark structure, located in the city’s Downtown Crossing area, was on the brink of collapse when Suffolk University invested $30 million to reconstruct it.

Suffolk University purchased the building from the city of Boston in 2008 in order to enable it to meet the growing needs of its theater program and provide a new student residence hall, according to Gordon B. King, the university’s senior director of facilities planning and management. “The reuse of the property fit well into Suffolk’s master plan, which called for the addition of new housing for 197 students,” he said.

HISTORICAL THEATER EXPERIENCES BOOM, THEN SUFFERS NEGLECT

Designed in 1876 by architect Levi Newcomb, the building originally housed two cast iron storefronts and a carpet storage warehouse. In 1913, the building underwent its first reconstruction. Architect Clarence Blackall was hired to convert the building into a theater for showing silent motion pictures. Blackall incorporated a marble addition into the main façade and inserted a narrow 800-seat auditorium into the basement and first three stories of the structure.

By the late 1920s, the theater was a trailblazer for “talkie” films. But it didn’t take long before the Modern was struggling to compete with larger, more up-to-date theaters throughout Boston. The owners struggled to fill the seats, but the long, slow decline of the theater was set in motion.

The 1970s saw a brief effort to rehabilitate the theater, but that failed and the structure was sold in the early 1980s. It sat largely untouched, rapidly deteriorating for more than 20 years until Suffolk University acquired it four years ago.

PROJECT SUMMARY

Modern Theatre, Suffolk University, Boston

Building Team

Owner/developer: Suffolk University

Architect: CBT Architects (co-submitter)

MEP engineer: Zade Associates

Structural engineers: McNamara/Salvia and Structures North Consulting Engineers Inc.

General contractor: Suffolk Construction Co. (co-submitter)General Information

Size: 70,000 sf

Construction cost: $30 million

Construction period: November 2008 to October 2010

Delivery method: Design-bid-build

DEVELOPING A TRULY ‘MODERN THEATRE’ FROM THE GROUND UP

When Suffolk University acquired the building, the interior was in such disrepair it was no more than a decaying shell—only the façade could be saved. A few original items were preserved, including a 26-foot-wide painted screen tapestry from the early 1900s Modern Theatre, along with some paneling, wall coverings, and cornices.

“The existing building was in very poor structural condition and was condemned by the city,” says Adam McCarthy, PE, a principal with McNamara/Salvia Inc., Boston. However, the Building Team was committed to designing a new theater that would invoke contemporary standards of comfort and technology, while echoing the form and feeling of the building’s past. In addition, a 10-story residence hall built atop the theater would serve as Suffolk University’s newest dormitory.

STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS BETWEEN RESIDENCE HALL AND FAÇADE

Because the original auditorium was very deep but extremely narrow, reconstruction of the Modern Theatre posed difficult structural design problems.

“We had many challenges with reincorporating the historic façade back in the project, with a major one being how the building movements from the new residential building could be accommodated by or isolated from the historic façade,” says McCarthy. “This led to a great deal of structural modeling and detailing to achieve the acquired goals.”

The narrow building design would make the tall, thin residential hall portion of the structure act like a sail in the wind. The structural engineers had to deal with the complexities associated with the softening of the transfer members created in the lateral force resisting system.

Transfer members carry the load from the residential floors above and spread it over the top of the performance space. With a mostly moment-frame reinforced steel structure, the tower deflects significantly more than the historic stone and masonry façade is able to accommodate.

“This required a carefully detailed and exactingly constructed set of slotted structural connections and expansion joints, as the stone façade still relies on the tower for lateral bracing in its weak axis,” says Adrian LeBuffe, senior associate and project architect with CBT Architects, Boston.

The Building Team next turned their attention to ensuring the original façade would fit seamlessly on the new structure.

Prior to tearing down the original structure, the Building Team spent two months studying, planning, and preparing for the removal of the façade and the restoration process.

As the Building Team deconstructed the white Vermont marble and sandstone exterior, each piece was individually cleaned and catalogued prior to reassembly. Total laser scanning was utilized to obtain exact profiles of each stone, and BIM was used to load the data into a 3D model. This enabled the Building Team to identify dimensional problems with the façade and eliminate conflicts due to the redesign of the new structure, including the façade’s interaction with structural steel. This allowed for the arrangement of special off-site fabrication to avoid any conflicts. As a result, masons were able to install the façade smoothly and efficiently.

“Despite the difficulty of façade deconstruction on a very tight site, a variety of difficult stone restoration issues, and the demands of façade reconstruction to modern code and programmatic requirements, the project went quite smoothly,” says LeBuffe.

The reconstruction of the Modern Theatre resulted in a unique venue in Boston. The Building Team revived a city landmark and included design elements that modernized the distinctive features of the original 1900s theater while preserving the building’s historic façade.

“The city’s vision for restoration and historic preservation in the Lower Washington Street area and [the Building Team’s] vision for this project were one and the same,” said King. “The restoration of the Modern Theatre—one of the area’s three landmark theatres, along with surrounding residential and commercial buildings, has brought beauty, vibrancy, and economic vitality back to the neighborhood.” +

Related Stories

| Apr 12, 2011

American Institute of Architects announces Guide for Sustainable Projects

AIA Guide for Sustainable Projects to provide design and construction industries with roadmap for working on sustainable projects.

| Apr 11, 2011

Wind turbines to generate power for new UNT football stadium

The University of North Texas has received a $2 million grant from the State Energy Conservation Office to install three wind turbines that will feed the electrical grid and provide power to UNT’s new football stadium.

| Apr 8, 2011

SHW Group appoints Marjorie K. Simmons as CEO

Chairman of the Board Marjorie K. Simmons assumes CEO position, making SHW Group the only firm in the AIA Large Firm Roundtable to appoint a woman to this leadership position

| Apr 5, 2011

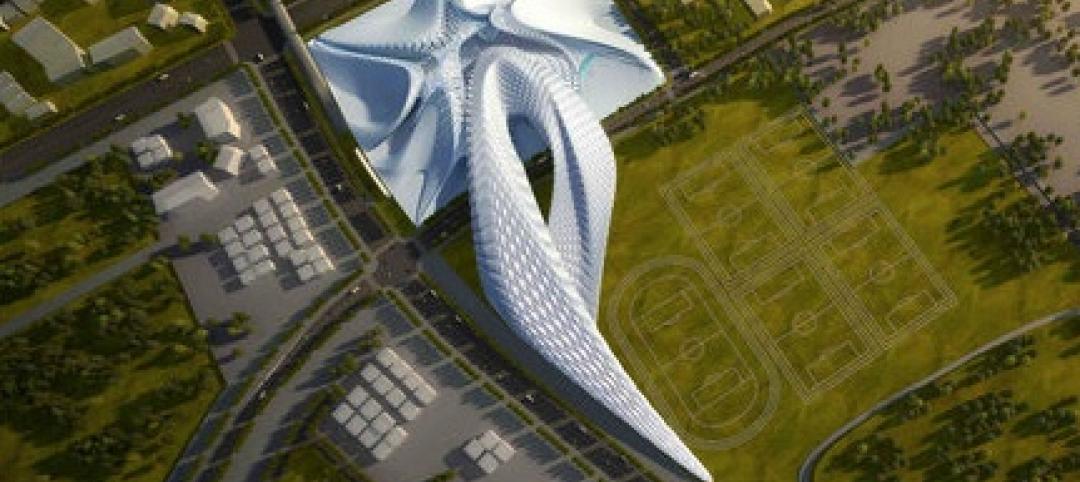

Zaha Hadid’s civic center design divides California city

Architect Zaha Hadid is in high demand these days, designing projects in Hong Kong, Milan, and Seoul, not to mention the London Aquatics Center, the swimming arena for the 2012 Olympics. But one of the firm’s smaller clients, the city of Elk Grove, Calif., recently conjured far different kinds of aquatic life when members of the City Council and the public chose words like “squid,” “octopus,” and “starfish” to describe the latest renderings for a proposed civic center.

| Apr 5, 2011

Are architects falling behind on BIM?

A study by the National Building Specification arm of RIBA Enterprises showed that 43% of architects and others in the industry had still not heard of BIM, let alone started using it. It also found that of the 13% of respondents who were using BIM only a third thought they would be using it for most of their projects in a year’s time.