The residents of nursing homes, long-term care, memory care, and assisted living facilities across the country comprise less than 1% of the U.S. population. When the final toll of novel coronavirus fatalities is calculated, it is almost certain that at least 25%—and possibly much more—will be the physically and/or cognitively frail residents as well as some of the staff of these facilities.

On May 10, The New York Times reported that 35% of all coronavirus deaths—27,700—were residents and workers at nursing homes and long-term care facilities, and in at least 14 states, more than half of all coronavirus deaths were tied to such facilities. This was all too predictable.

Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are the biggest problem. Most of the 1.7 million U.S. nursing home beds were built 40-60 years ago. The model for skilled nursing as well as the governing codes at the time created the petri dish situation we face today. Most residents share a minimally sized room with one to three roommates clustered in 40-60 bed nursing units.

Even in more progressive states like New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania the minimum space mandated by code per resident in a semi-private room is only 80 sf. Most developers and operators have regarded the code to be the maximum needed. Moreover, many older facilities provide even less than that very tight minimum.

In addition, most are thinly staffed with trained personnel. Thus, social distancing and other basic protective measures are impossible in these facilities.

The equally vulnerable residents of memory care and assisted living facilities have usually fared somewhat better. Most of the newer memory care facilities operate in smaller “houses” that can reduce the likelihood of a widespread outbreak. In assisted living the residents have their own rooms or apartments which allow them to shelter in place. Nevertheless, even here, deaths have occurred.

NEEDED: A MAJOR REVIEW OF NURSING HOME DESIGN

If there is not a major reevaluation of how we house and care for our most frail and vulnerable, this tragic event will repeat with every widespread health crisis. Much of the current inventory of facilities was poorly conceived and amounts to warehousing our frailest citizens in unsafe conditions.

Much of the senior living and care industry, however, has successfully managed the crisis. Continuing care retirement communities, independent living facilities with services, and most of the newer assisted living communities have trained staffs, existing protocols to protect residents during an outbreak of an infectious disease, and the services (home delivery of meals, regular disinfecting and deep cleaning, etc.) that allow their residents to safely isolate and shelter in place.

Facilities providing long-term housing and care are a vital resource for America. Every year hundreds of thousands become frail and are often suffering from chronic health conditions. At that point they often face the cold fact that they do not have good affordable options for housing and care. Medicaid and Medicare were passed, in part, to address this issue. Unfortunately, the implementation guidelines for these programs have often reinforced some of the worst aspects of much of the nursing home and long-term care industry.

A private room at the Goodwin House in Alexandria, Va., designed by Perkins Eastman. Private rooms allow for greater isolation from the coronavirus. Photo: © Sarah Mechling, Courtesy Perkins Eastman

5 KEY FACTORS IN THE NURSING HOME CORONAVIRUS CRISIS

Five major factors have directly contributed to the current crisis:

- The vast majority of long-term care facilities have multi-bed rooms as well as congregate activities and dining areas that preclude isolation, social distancing, extensive cleaning and disinfecting, and other essential mitigation measures. In most assisted living facilities the residents have their own rooms or apartments, but the design of many memory care units, which are often wings of old long-term care facilities, makes isolation and social distancing difficult. Thus, once the virus gets into a facility, it can spread with devastating effect.

- The majority of long-term care beds are in for-profit facilities, and most of the residents are covered by Medicaid or Medicare. The long-term federal and state efforts to slow the growth of Medicaid and Medicare expenses have narrowed the margins to the point that most nursing homes and long-term care facilities did not have adequate numbers of trained staff, the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE), facilities that permitted isolation, appropriate cleaning materials and protocols, or other basic resources necessary to deal with an outbreak of such a virulent virus.

- While the majority of the revenues in the nursing and long-term care industry come from Medicaid and Medicare, the reimbursement rates in most states build in little or no funding for capital improvements or development of new facilities.

- Even though most facilities quickly stopped visits by family members (except at times of end-of-life visits) and other non-essential persons, the staff were often coming to work each day from the very communities where the infection rates were the highest. Moreover, many staff members are so minimally paid that they have second jobs in the community, further multiplying their chance of exposure and contagion.

- While the more professionally run facilities implemented strict screening and temperature checking at their entrances, we have all learned that many infected persons are asymptomatic. Only regular and rapid turnaround testing can deal with this issue, but such testing capacity simply does not yet exist.

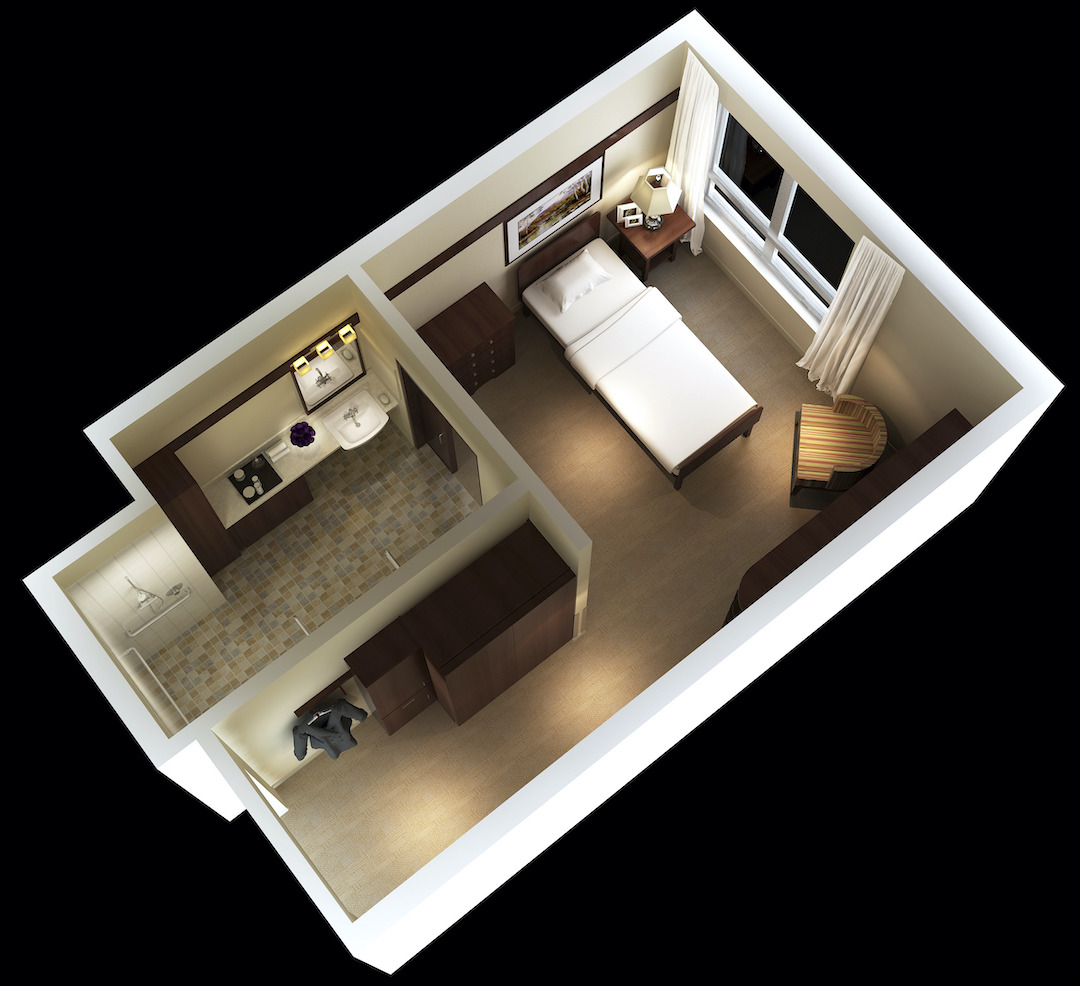

A private resident room with expanded accessibility at the JGS Lifecare: Sosin Rehabilitation Center, Longmeadow, Mass. Rendering: Perkins Eastman

SOME MITIGATION MEASURES ARE BEING IMPLEMENTED

In the interim, the more professionally run facilities implemented as many of the known mitigation measures as possible:

- They secured their perimeters and restricted almost all entry to a single location where screening and control were possible. Deliveries were also restricted to a dedicated entry where their contents could be screened and disinfected before being brought into the facility.

- All residents were required to self-isolate in their rooms or units.

- All group dining and activities were canceled. Meals were delivered to residents’ rooms.

- Regular cleaning and disinfecting of all surfaces likely to be touched by residents—elevator buttons, hand or lean rails, etc.—were stepped up. This has become very important because even though this topic is still being researched, the virus appears to be able to live for up to 72 hours on steel, 4 hours on copper, and 24 hours on cardboard.

- Staff use of PPE, including masks, shields or goggles, gloves, and gowns, was mandated.

All of this was often not enough, and even well-run facilities have had multiple deaths. Therefore, when this pandemic is more under control, a nationwide discussion about the measures that need to be implemented to minimize the impact of another wave of the novel coronavirus (or the next virus) is imperative. Some changes will be relatively easy to implement, but others will be very hard and expensive. These expenses, however, are something that we as a society that cares about our frailest will have to bear.

The most difficult question is what to do with the obsolete existing facilities. The fundamental problem with most of the older long-term care facilities is the small number of private rooms. Without the ability to safely isolate a resident in a private room, it is hard to effectively mitigate a pandemic. The shift to all-private room designs started in the 1980s but was largely limited to leading nonprofit sponsors and facilities catering to high-end private-pay residents. As we have noted, the vast majority of U.S. nursing home residents still have one or more roommates.

At Blue Skies of Texas East, in San Antonio, residential-scaled living, including dining and a kitchen supporting a group of 13 residents, was designed by Perkins Eastman. This contrasts starkly with large institutional congregate spaces in traditional 40- to 60-resident nursing unit configurations commonly found in nursing homes from the 1950s and 1960s. Photo: Casey Dunn

At Blue Skies of Texas East, in San Antonio, residential-scaled living, including dining and a kitchen supporting a group of 13 residents, was designed by Perkins Eastman. This contrasts starkly with large institutional congregate spaces in traditional 40- to 60-resident nursing unit configurations commonly found in nursing homes from the 1950s and 1960s. Photo: Casey Dunn

A 13-POINT PLAN FOR DESIGNING SENIOR LIVING FACILITIES

At Perkins Eastman, we are working to help our senior living clients prepare for any future pandemic. Some things are already clear, and we are building the following 13 factors into our standard planning and design guidelines:

- Site planning should include features that allow a facility to secure its perimeter so it can strictly control ingress and egress.

- Building designs should permit the facility to funnel personnel access to one location sized and equipped to permit effective screening. All service deliveries should be restricted to a separate entry point sized to permit packages to be disinfected prior to bringing them into the building.

- All facilities must have increased clean storage for emergency stocks of PPE, temperature testing equipment, toilet paper, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies, etc.

- Interior finishes and furniture need to be selected in part on whether they can facilitate and withstand the more frequent and harsher cleaning protocols necessary for disinfection.

- Senior living facilities—even independent living communities—should consider having a space that can serve as a small health center that permits examination of residents, and, in times of crisis, isolation and care of some residents.

- All facilities should have a telehealth connection to a backup healthcare provider.

- Where feasible, senior living facilities should have spaces that can be temporarily converted to provide accommodations for staff to stay overnight during a health crisis to minimize their being infected out in the community

- More attention needs to be placed on “Well Design” principles—especially those to do with indoor air quality, appropriate lighting and daylighting, and wellness.

- Mechanical systems need to be designed with the spread of infectious disease in mind. Air filtration, humidification, UV sanitizing, zoning and decentralizing HVAC systems, increased air changes, and many other factors are all part of this planning.

UV LIGHT, DECENTRALIZED HVAC SYSTEMS, HIGHER RATES OF HUMIDIFICATION IN RESIDENT ROOMS

For example, while filters are advisable for air quality reasons, the novel coronavirus particles are so small that filters will not catch them. UV light can be used to sanitize some spaces when not occupied, such as public bathrooms at night, but UV light is not considered safe to use in occupied spaces.

Greater consideration needs to be given to decentralized HVAC systems and/or the ability to operate any central ducted systems in zones to contain the spread of infectious diseases. Higher rates of humidification are also needed so that the water droplets in the air can catch the virus and make it fall to the ground more quickly. MEP engineers are already publishing papers and issuing guidelines on these issues.

The JGS Lifecare: Sosin Rehabilitation Center, Longmeadow, Mass., homelike in size and character, provides dining and living rooms for a house of 12 residents. These small houses, designed by Perkins Eastman, require a limited number of focused staff, which reduces the number of people entering the space where residents are located. Photo: © Andrew Rugge, Courtesy Perkins Eastman

- Residents or couples should have units that allow them to shelter in place; these units should be equipped with up to date emergency notification technology, telemonitoring of vital signs for those with chronic conditions (this technology exists but has yet to be widely deployed), robust Wi-Fi, and other smart home technologies.

- Safe access should be provided for all residents to outdoor spaces that permit social distancing. As is now standard practice, these outdoor areas should be fenced or naturally contained to keep residents secure.

- Private rooms or apartments should be an option for all residents and couples. All future long-term care and memory care beds should be designed as private rooms and organized to minimize the spread of infectious diseases. What to do about existing obsolete facilities in the future is a topic too large and complex to cover here.

- Greater consideration should be given to the “small house” concept, which is being implemented across the country by the Veterans Administration and other senior living operators. Facilities developed in accordance with this concept house 12-14 residents—each with their own room—in a houselike setting with its own dining and activity spaces.

These facilities have been built as single-story structures (resembling a typical ranch home) and on a floor or wing of a multistory building. Each small house operates as a self-contained unit with its own cooking, dining, and activity spaces; each is served by a small, dedicated team. This concept greatly facilitates safe, shelter-in-place efforts during a pandemic.

NO MATTER WHAT, WE CAN'T GO BACK TO THE OLD WAYS

When this pandemic is finally contained, we will undoubtedly have learned more about which “best practices” must be built into senior living facilities. One fact is immutable, however: Going back to the status quo ante is not an option.

Jewish Senior Life: Green House, Rochester, N.Y., designed by Perkins Eastman, includes three houses of 12 residents. Each house is self-sufficient. Staff members are cross-trained to take on multiple roles in each house, an approach that greatly reduces the number of people who enter and exit, which reduces the risk of virus spread. Photo: © Sarah Mechling, Courtesy Perkins Eastman

Jewish Senior Life: Green House, Rochester, N.Y., designed by Perkins Eastman, includes three houses of 12 residents. Each house is self-sufficient. Staff members are cross-trained to take on multiple roles in each house, an approach that greatly reduces the number of people who enter and exit, which reduces the risk of virus spread. Photo: © Sarah Mechling, Courtesy Perkins Eastman

Bradford Perkins is Founder and Chairman of Perkins Eastman Architects, an international architecture, interior design, and planning firm headquartered in New York with offices in 11 U.S. cities as well as Canada, China, Ecuador, India, and the UAE. The firm has provided senior living design services to over 600 clients across North America and around the world. Perkins is the primary author of a widely used textbook, Building Type Basics for Senior Living (Wiley).

Martin Siefering is Co-National Practice Leader for Senior Living at Perkins Eastman.

Related Stories

Coronavirus | Oct 2, 2020

With revenues drying up, colleges reexamine their student housing projects

Shifts to online learning raise questions about the value of campus residence life.

Coronavirus | Oct 1, 2020

The Weekly show: Decarbonizing Chicago, re-evaluating delayed projects, and the future of the jobsite

The October 1 episode of BD+C's "The Weekly" is available for viewing on demand.

Coronavirus | Sep 28, 2020

Cities to boost spending on green initiatives after the pandemic

More bikeways, car restrictions, mass transit, climate resilience are on tap.

Coronavirus | Sep 28, 2020

Evaluating and investing resources to navigate past the COVID-19 pandemic

As AEC firm leaders consider worst-case scenarios and explore possible solutions to surmount them, they learn to become nimble, quick, and ready to pivot as circumstances demand.

Coronavirus | Sep 24, 2020

The Weekly show: Building optimization tech, the future of smart cities, and storm shelter design

The September 24 episode of BD+C's "The Weekly" is available for viewing on demand.

Coronavirus | Sep 10, 2020

Mobile ordering is a centerpiece of Burger King’s new design

Its reimagined restaurants are 60% smaller, with several pickup options.

Coronavirus | Sep 9, 2020

Prefab: Construction’s secret weapon against COVID-19

How to know if offsite production is right for your project.

Coronavirus | Sep 3, 2020

The Weekly show: JLL's construction outlook for 2020, and COVID-19's impact on sustainability

The September 3 episode of BD+C's "The Weekly" is available for viewing on demand.

Coronavirus | Sep 1, 2020

6 must reads for the AEC industry today: September 1, 2020

Co-working developers pivot to survive the pandemic, and the rise of inquiry-based learning in K-12 communities.

Coronavirus | Aug 28, 2020

7 must reads for the AEC industry today: August 28, 2020

Hotel occupancy likely to dip by 29%, and pandemic helps cannabis industry gain firmer footing.