Success is often measured in terms of specific solutions to definite questions. But a new movement known as “maker culture” is beginning to change that mentality.

Maker culture recognizes that a successful solution is built on a makeshift pedestal of untenable theories, interesting but impractical prototypes, and concepts that were puzzled over from dusk until dawn but never managed to bloom.

It is this makeshift pedestal, and not solely what sits atop it, that maker culture is most concerned with. “Fail” is no longer a dirty four-letter word: for maker culture, it has become a crucial stop along the way.

“In contemporary culture, you see an acceptance of failure that wasn’t there before,” says Pablo Savid-Buteler, LEED AP, Managing Principal, Sasaki Associates. “If you’re going to fail, you want to fail often, in pursuit of an achievement.”

How success is measured is also changing. The AEC industry no longer judges professional success by traditional benchmarks—the car you drive, the size of your house, says Brad Prestbo, AIA, CSI, CDT, Senior Associate, Sasaki. The true measure of success boils down to this: What have you created?

What, then, is maker culture? How has it turned failure into a salient part of the game? And what purpose does it serve for the AEC industry?

At its most basic, maker culture is about making things; specifically, using “technology to create something visible and tangible,” writes Gensler’s Douglas Wittnebel, AIA, IIDA, LEED AP BD+C, Design Director/Principal, in a GenslerOn blog post (http://bit.ly/2c71bHX). “The maker movement focuses on physical explorations, the act of doing and creating and making; it requires participants to get their hands dirty, test ideas, and try new approaches. And then feel and smell and sometimes taste the results,” he writes.

The emphasis is on the act of creating in order to get a first-hand look at the results, whether good, bad, or a bit of both. In the maker movement, “doing” is usually more important than what has actually been done.

For the AEC industry, this means bringing together professionals who may not ordinarily work together to flex their intellectual muscles.

Sasaki’s maker program provides new employees with a multi-week fabrication program. The goal: design and build a physical object. Last year, it was a chair; this year, a table. The purpose, Prestbo explains, is to expose designers to the fabrication process and get their hands dirty.

A Sasaki employee puts the firm's maker spaces in its Watertown, Mass., office to use. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

A Sasaki employee puts the firm's maker spaces in its Watertown, Mass., office to use. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

There has always been a model workshop or fabrication space at Sasaki’s Watertown, Mass., office, but management determined that the entire office needed to become a laboratory, suitable for tinkering and making. The maker shop continues to grow every year, but now 3D printing stations can be found all across the building. The plan is to redesign workstations to make room for more creative and collaborative spaces.

At NBBJ, the firm’s Design Computation Group tries to put on at least one hackathon event every quarter. In the last two years, NBBJ has hosted six internal hackathons and participated in a number of external events.

Every NBBJ studio has a woodshop and a maker space with such tools as 3D printers and laser cutters, but staff members have the ability to use basically any part of the firm as a workspace. “We’re not relegated to any corner, and can do our work properly any place in the firm,” says Dan Anthony, Design Computation Leader in NBBJ’s Design Computation Group.

SOLUTIONS FOR A RESULTS-DRIVEN WORLD

Maker culture allows for success in many different ways, but “ultimate success” (as Savid-Buteler refers to it) or “maximum fulfillment” (in Anthony’s words) propels the movement.

Ultimate success—or maximum fulfillment—is defined as an idea that was initially born in a maker space or during a hackathon, went on to become a prototype, and then advanced to become a building solution or achieve a practical use in the real world.

Take this question designers at NBBJ asked themselves during one of the firm’s internal hackathons: Wouldn’t it be great if we could know what was happening with our building’s environment in real time and allow occupants, not just facility managers, to respond to that information?

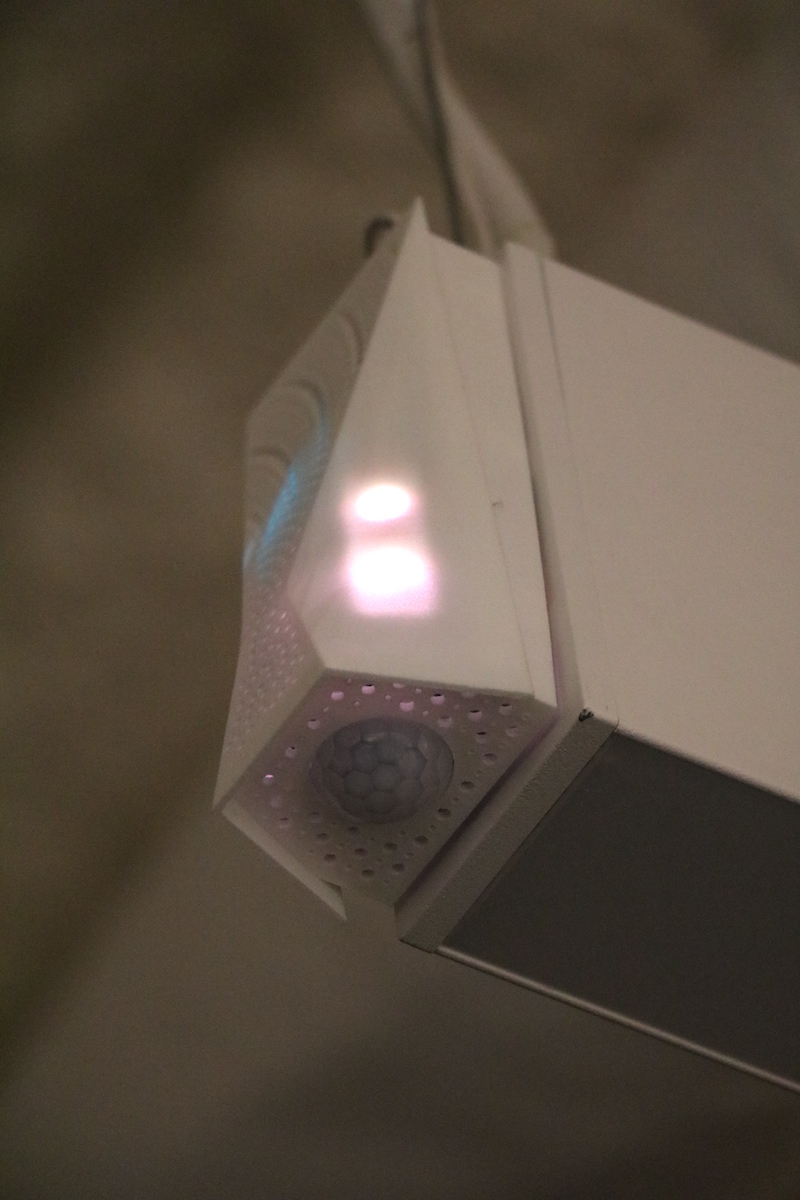

The rest of the hackathon was devoted to producing concepts and sketching out prototypes as possible answers to that question. The result came in the shape of sensor technology that can collect data and track light levels, humidity, motion, and sound (the first sensor of its kind to incorporate sound as a measurable parameter), then link this information via an accompanying app to help employees find a workspace that fits their comfort needs: cool/warm, bright/muted, or any other combination.

The accompanying Goldilocks app allows users to find the office location that best fits their needs. Photo courtesy of NBBJ.

The accompanying Goldilocks app allows users to find the office location that best fits their needs. Photo courtesy of NBBJ.

Think of it as allowing Goldilocks to find the porridge that was just right without ever having to burn her tongue or eat cold gruel. More than 50 such sensors have been installed in NBBJ’s New York City offices, providing staff with real-time environmental feedback. Now, any NBBJ employee in the New York office can find a work spot that is just right, which is why NBBJ gave its new sensor technology the clever folktale-inspired name of “Goldilocks.”

Goldilocks is still in its fledgling state, but the data collected will help plan spaces for future projects and some clients have already shown interest in using the technology. “We found that in order to get the kind of performance we needed, we had to build our own,” says Anthony.

Sasaki has seen this doing/prototyping mentality born of in-house maker spaces leave its mark not only in the building artifact form, but also in developing a new approach to building projects, such as the inclusion of prototyping as part of its planning services.

An international client came to Sasaki and asked them to develop a theoretical model campus with a design they could apply to any of their 32 campuses across their country. Instead of creating a master plan, Sasaki developed an entire tool kit, a catalogue of solutions, that would allow the client to combine, aggregate, and recombine the pieces in different ways to come up with solutions for a new or existing campus.

Here is where the maker mentality really makes itself known; the idea was that the space prototypes could be fabricated completely in a maker space and then configured as needed.

The first prototype is currently being built on the client’s main campus. The building will have a traditionally constructed foundation and ground structure, but the rest is being fabricated in an offsite shop, transported, and assembled on site. “This is an example of how the idea of prototyping solutions in the environment of a maker space can be scaled up to deliver a complete building solution,” says Savid-Buteler.

DIGITAL SPACE FOR DIGITAL MAKERS

Maker culture may often be associated with the physical work you’d expect to see in a workshop: soldering, sawing, hammering, and the like. But the digital side of maker culture is becoming just as prominent.

A lot of what NBBJ designers do is digital. There is a healthy mix of working with materials and tinkering in a physical space while also using technology or software tools.

With Goldilocks, the hardware—the physical sensors—led directly to a digital realm. How useful would the hardware be if users could not monitor the data it was collecting in real time? It is the digital space that connects the hardware to the solution.

Software may act as the bridge between a piece of hardware and its intended use, but it can also act as a bridge between the initial idea and the prototype. “The software side is as important and really drives a lot of the fabrication side of things,” says Sasaki Associate Colin Booth.

Sasaki’s Strategies group is made up of programmers, software developers, analysts, and mathematicians whose mission is to take a specific question and create an entire exercise around finding a solution for that question. The solution is completely customized with scripting to result in form and material solutions. While the preliminary question is specific, the answer is open-ended and the testing is completely digital. The doing, or making, cannot start without the preparatory digital component.

The Sasaki Offices also allow for digital making. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

The Sasaki Offices also allow for digital making. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

MIXING MAKER CULTURE WITH COMPANY CULTURE

The success of a firm’s attempts at integrating a maker program into the overall picture of the company is not solely based on the creation of new products or building solutions like NBBJ’s Goldilocks sensor or Sasaki’s model campus.

For every Goldilocks that comes out of a hackathon, there are a number of ideas and innovations that don’t pan out. But these “failed” ideas are not simply velleities, never to serve an actual purpose. They often become tools or showcases for further learning by NBBJ’s designers.

“We’ve found sometimes that although a particular tool is a showcase, it inspires new ideas in different areas,” Anthony says. “Healthcare, our commercial practice, our urban development and design—all of those markets are influenced by things we discover at hackathons.”

Anthony says NBBJ views maker culture as an antidote to the rigidity and structure that can stifle innovation, imagination, and creation. Maker culture prefers to exist as a culture of scrappy tinkerers, forgoing sterile, white labs for workshops more closely resembling a high school shop class. “We constantly come back to that scrappy maker place,” Anthony says. “We want to be able to think about what might be on the horizon.”

Sasaki’s Savid-Buteler says the simple process of discovery inherent in the firm’s maker program is having the greatest impact on the firm’s culture. “The impact that it has is that you begin to develop a new mindset,” says Savid-Buteler. “We find that to be very, very exciting.”

Maker culture, regardless of industry, takes innovation and breaks it down to its base elements in order to create, using what one of the greatest tinkerers who ever lived, Thomas Edison, described as the only two things necessary for invention: a good imagination and a pile of junk.

Related Stories

| Mar 2, 2011

How skyscrapers can save the city

Besides making cities more affordable and architecturally interesting, tall buildings are greener than sprawl, and they foster social capital and creativity. Yet some urban planners and preservationists seem to have a misplaced fear of heights that yields damaging restrictions on how tall a building can be. From New York to Paris to Mumbai, there’s a powerful case for building up, not out.

| Mar 1, 2011

Smart cities: getting greener and making money doing it

The Global Green Cities of the 21st Century conference in San Francisco is filled with mayors, architects, academics, consultants, and financial types all struggling to understand the process of building smarter, greener cities on a scale that's practically unimaginable—and make money doing it.

| Mar 1, 2011

How to make rentals more attractive as the American dream evolves, adapts

Roger K. Lewis, architect and professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Maryland, writes in the Washington Post about the rising market demand for rental housing and how Building Teams can make these properties a desirable choice for consumer, not just an economically prudent and necessary one.

| Mar 1, 2011

New survey shows shifts in hospital construction projects

America’s hospitals and health systems are focusing more on renovation or expansion than new construction, according to a new survey conducted by Health Facilities Management magazine and the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE). In fact, renovation or expansion accounted for 73% of construction projects at hospitals responding to the survey.

| Mar 1, 2011

AIA selects 6 communities for long-term sustainability program

The American Institute of Architects today announced it has selected 6 communities throughout the country to receive technical assistance under the Sustainable Design Assessment Team (SDAT) program in 2011. The communities selected are Shelburne, Vt., Apple Valley, Mn., Pikes Peak Region, Co., Southwest DeKalb County, Ga., Bastrop, Tx., and Santa Rosa, Ca. The SDAT program represents a significant institutional investment by the AIA in public service work to assist communities in developing policy frameworks and long term sustainability plans.

| Feb 24, 2011

Perkins+Will designs 100 LEED Certified buildings

Perkins+Will announced the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification of its 100th sustainable building, marking a key milestone for the firm and for the sustainable design industry. The Vancouver-based Dockside Green Phase Two Balance project marks the firm’s 100th LEED certified building and is tied for the highest scoring LEED building worldwide with its sister project, Dockside Green Phase One.

| Feb 24, 2011

New reports chart path to net-zero-energy commercial buildings

Two new reports from the Zero Energy Commercial Buildings Consortium (CBC) on achieving net-zero-energy use in commercial buildings say that high levels of energy efficiency are the first, largest, and most important step on the way to net-zero.

| Feb 24, 2011

Lending revives stalled projects

An influx of fresh capital into U.S. commercial real estate is bringing some long-stalled development projects back to life and launching new construction of apartments, office buildings and shopping centers, according to a Wall Street Journal article.

| Feb 23, 2011

London 2012: What Olympic Park looks like today

London 2012 released a series of aerial images that show progress at Olympic Park, including a completed roof on the stadium (where seats are already installed), tile work at the aquatic centre, and structural work complete on more than a quarter of residential projects at Olympic Village.

| Feb 23, 2011

Call for Entries: 2011 Building Team Awards, Deadline: March 25, 2011

The 14th Annual Building Team Awards recognizes newly built projects that exhibit architectural and construction excellence—and best exemplify the collaboration of the Building Team, including the owner, architect, engineer, and contractor.