Success is often measured in terms of specific solutions to definite questions. But a new movement known as “maker culture” is beginning to change that mentality.

Maker culture recognizes that a successful solution is built on a makeshift pedestal of untenable theories, interesting but impractical prototypes, and concepts that were puzzled over from dusk until dawn but never managed to bloom.

It is this makeshift pedestal, and not solely what sits atop it, that maker culture is most concerned with. “Fail” is no longer a dirty four-letter word: for maker culture, it has become a crucial stop along the way.

“In contemporary culture, you see an acceptance of failure that wasn’t there before,” says Pablo Savid-Buteler, LEED AP, Managing Principal, Sasaki Associates. “If you’re going to fail, you want to fail often, in pursuit of an achievement.”

How success is measured is also changing. The AEC industry no longer judges professional success by traditional benchmarks—the car you drive, the size of your house, says Brad Prestbo, AIA, CSI, CDT, Senior Associate, Sasaki. The true measure of success boils down to this: What have you created?

What, then, is maker culture? How has it turned failure into a salient part of the game? And what purpose does it serve for the AEC industry?

At its most basic, maker culture is about making things; specifically, using “technology to create something visible and tangible,” writes Gensler’s Douglas Wittnebel, AIA, IIDA, LEED AP BD+C, Design Director/Principal, in a GenslerOn blog post (http://bit.ly/2c71bHX). “The maker movement focuses on physical explorations, the act of doing and creating and making; it requires participants to get their hands dirty, test ideas, and try new approaches. And then feel and smell and sometimes taste the results,” he writes.

The emphasis is on the act of creating in order to get a first-hand look at the results, whether good, bad, or a bit of both. In the maker movement, “doing” is usually more important than what has actually been done.

For the AEC industry, this means bringing together professionals who may not ordinarily work together to flex their intellectual muscles.

Sasaki’s maker program provides new employees with a multi-week fabrication program. The goal: design and build a physical object. Last year, it was a chair; this year, a table. The purpose, Prestbo explains, is to expose designers to the fabrication process and get their hands dirty.

A Sasaki employee puts the firm's maker spaces in its Watertown, Mass., office to use. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

A Sasaki employee puts the firm's maker spaces in its Watertown, Mass., office to use. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

There has always been a model workshop or fabrication space at Sasaki’s Watertown, Mass., office, but management determined that the entire office needed to become a laboratory, suitable for tinkering and making. The maker shop continues to grow every year, but now 3D printing stations can be found all across the building. The plan is to redesign workstations to make room for more creative and collaborative spaces.

At NBBJ, the firm’s Design Computation Group tries to put on at least one hackathon event every quarter. In the last two years, NBBJ has hosted six internal hackathons and participated in a number of external events.

Every NBBJ studio has a woodshop and a maker space with such tools as 3D printers and laser cutters, but staff members have the ability to use basically any part of the firm as a workspace. “We’re not relegated to any corner, and can do our work properly any place in the firm,” says Dan Anthony, Design Computation Leader in NBBJ’s Design Computation Group.

SOLUTIONS FOR A RESULTS-DRIVEN WORLD

Maker culture allows for success in many different ways, but “ultimate success” (as Savid-Buteler refers to it) or “maximum fulfillment” (in Anthony’s words) propels the movement.

Ultimate success—or maximum fulfillment—is defined as an idea that was initially born in a maker space or during a hackathon, went on to become a prototype, and then advanced to become a building solution or achieve a practical use in the real world.

Take this question designers at NBBJ asked themselves during one of the firm’s internal hackathons: Wouldn’t it be great if we could know what was happening with our building’s environment in real time and allow occupants, not just facility managers, to respond to that information?

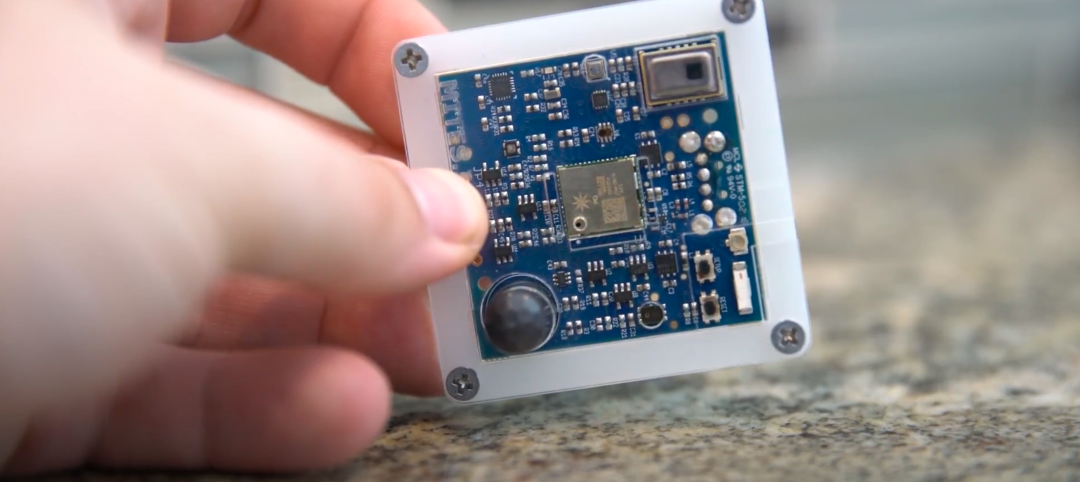

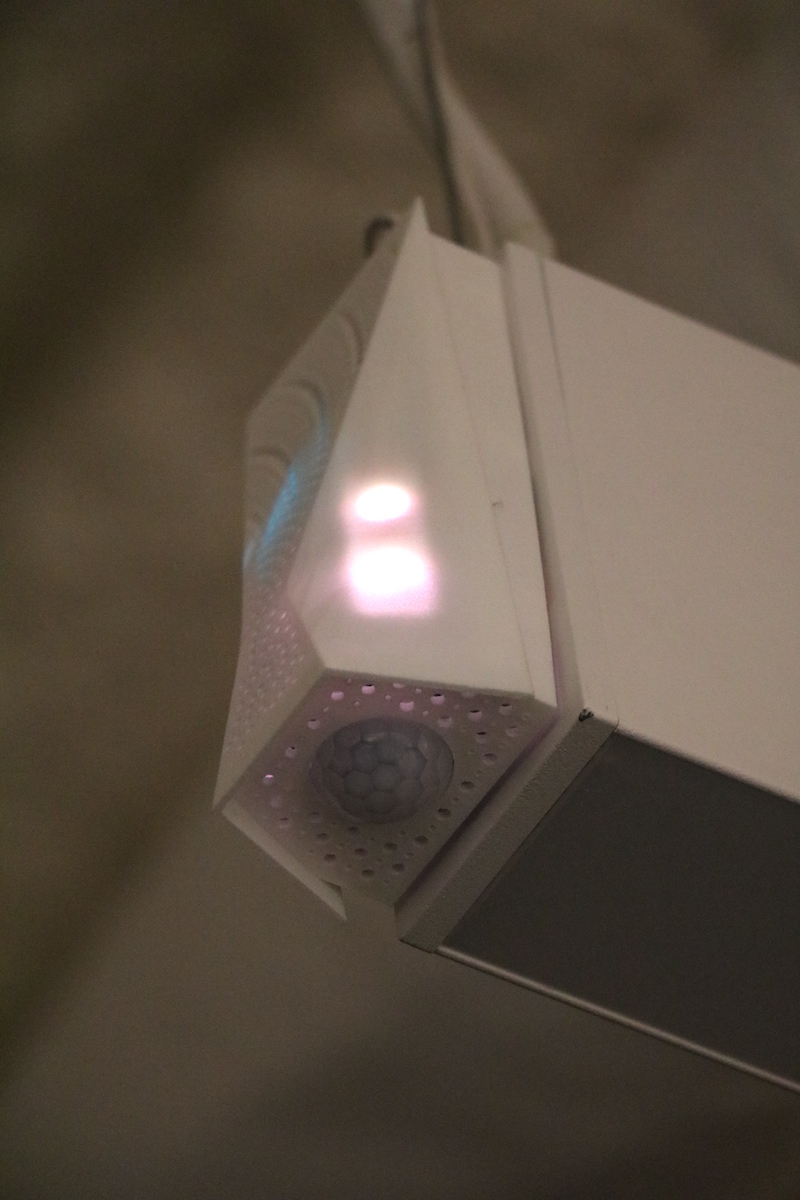

The rest of the hackathon was devoted to producing concepts and sketching out prototypes as possible answers to that question. The result came in the shape of sensor technology that can collect data and track light levels, humidity, motion, and sound (the first sensor of its kind to incorporate sound as a measurable parameter), then link this information via an accompanying app to help employees find a workspace that fits their comfort needs: cool/warm, bright/muted, or any other combination.

The accompanying Goldilocks app allows users to find the office location that best fits their needs. Photo courtesy of NBBJ.

The accompanying Goldilocks app allows users to find the office location that best fits their needs. Photo courtesy of NBBJ.

Think of it as allowing Goldilocks to find the porridge that was just right without ever having to burn her tongue or eat cold gruel. More than 50 such sensors have been installed in NBBJ’s New York City offices, providing staff with real-time environmental feedback. Now, any NBBJ employee in the New York office can find a work spot that is just right, which is why NBBJ gave its new sensor technology the clever folktale-inspired name of “Goldilocks.”

Goldilocks is still in its fledgling state, but the data collected will help plan spaces for future projects and some clients have already shown interest in using the technology. “We found that in order to get the kind of performance we needed, we had to build our own,” says Anthony.

Sasaki has seen this doing/prototyping mentality born of in-house maker spaces leave its mark not only in the building artifact form, but also in developing a new approach to building projects, such as the inclusion of prototyping as part of its planning services.

An international client came to Sasaki and asked them to develop a theoretical model campus with a design they could apply to any of their 32 campuses across their country. Instead of creating a master plan, Sasaki developed an entire tool kit, a catalogue of solutions, that would allow the client to combine, aggregate, and recombine the pieces in different ways to come up with solutions for a new or existing campus.

Here is where the maker mentality really makes itself known; the idea was that the space prototypes could be fabricated completely in a maker space and then configured as needed.

The first prototype is currently being built on the client’s main campus. The building will have a traditionally constructed foundation and ground structure, but the rest is being fabricated in an offsite shop, transported, and assembled on site. “This is an example of how the idea of prototyping solutions in the environment of a maker space can be scaled up to deliver a complete building solution,” says Savid-Buteler.

DIGITAL SPACE FOR DIGITAL MAKERS

Maker culture may often be associated with the physical work you’d expect to see in a workshop: soldering, sawing, hammering, and the like. But the digital side of maker culture is becoming just as prominent.

A lot of what NBBJ designers do is digital. There is a healthy mix of working with materials and tinkering in a physical space while also using technology or software tools.

With Goldilocks, the hardware—the physical sensors—led directly to a digital realm. How useful would the hardware be if users could not monitor the data it was collecting in real time? It is the digital space that connects the hardware to the solution.

Software may act as the bridge between a piece of hardware and its intended use, but it can also act as a bridge between the initial idea and the prototype. “The software side is as important and really drives a lot of the fabrication side of things,” says Sasaki Associate Colin Booth.

Sasaki’s Strategies group is made up of programmers, software developers, analysts, and mathematicians whose mission is to take a specific question and create an entire exercise around finding a solution for that question. The solution is completely customized with scripting to result in form and material solutions. While the preliminary question is specific, the answer is open-ended and the testing is completely digital. The doing, or making, cannot start without the preparatory digital component.

The Sasaki Offices also allow for digital making. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

The Sasaki Offices also allow for digital making. Photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates.

MIXING MAKER CULTURE WITH COMPANY CULTURE

The success of a firm’s attempts at integrating a maker program into the overall picture of the company is not solely based on the creation of new products or building solutions like NBBJ’s Goldilocks sensor or Sasaki’s model campus.

For every Goldilocks that comes out of a hackathon, there are a number of ideas and innovations that don’t pan out. But these “failed” ideas are not simply velleities, never to serve an actual purpose. They often become tools or showcases for further learning by NBBJ’s designers.

“We’ve found sometimes that although a particular tool is a showcase, it inspires new ideas in different areas,” Anthony says. “Healthcare, our commercial practice, our urban development and design—all of those markets are influenced by things we discover at hackathons.”

Anthony says NBBJ views maker culture as an antidote to the rigidity and structure that can stifle innovation, imagination, and creation. Maker culture prefers to exist as a culture of scrappy tinkerers, forgoing sterile, white labs for workshops more closely resembling a high school shop class. “We constantly come back to that scrappy maker place,” Anthony says. “We want to be able to think about what might be on the horizon.”

Sasaki’s Savid-Buteler says the simple process of discovery inherent in the firm’s maker program is having the greatest impact on the firm’s culture. “The impact that it has is that you begin to develop a new mindset,” says Savid-Buteler. “We find that to be very, very exciting.”

Maker culture, regardless of industry, takes innovation and breaks it down to its base elements in order to create, using what one of the greatest tinkerers who ever lived, Thomas Edison, described as the only two things necessary for invention: a good imagination and a pile of junk.

Related Stories

Urban Planning | Apr 12, 2023

Watch: Trends in urban design for 2023, with James Corner Field Operations

Isabel Castilla, a Principal Designer with the landscape architecture firm James Corner Field Operations, discusses recent changes in clients' priorities about urban design, with a focus on her firm's recent projects.

3D Printing | Apr 11, 2023

University of Michigan’s DART Laboratory unveils Shell Wall—a concrete wall that’s lightweight and freeform 3D printed

The University of Michigan’s DART Laboratory has unveiled a new product called Shell Wall—which the organization describes as the first lightweight, freeform 3D printed and structurally reinforced concrete wall. The innovative product leverages DART Laboratory’s research and development on the use of 3D-printing technology to build structures that require less concrete.

Market Data | Apr 11, 2023

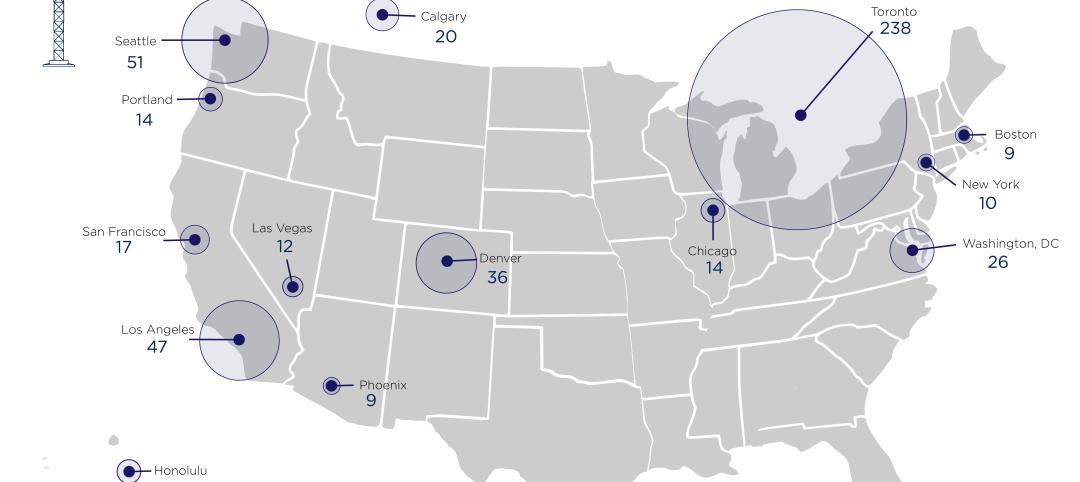

Construction crane count reaches all-time high in Q1 2023

Toronto, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Denver top the list of U.S/Canadian cities with the greatest number of fixed cranes on construction sites, according to Rider Levett Bucknall's RLB Crane Index for North America for Q1 2023.

University Buildings | Apr 11, 2023

Supersizing higher education: Tracking the rise of mega buildings on university campuses

Mega buildings on higher education campuses aren’t unusual. But what has been different lately is the sheer number of supersized projects that have been in the works over the last 12–15 months.

Architects | Apr 10, 2023

Bill Hellmuth, FAIA, Chairman and CEO of HOK, dies at 69

William (Bill) Hellmuth, FAIA, the Chairman and CEO of HOK, passed away on April 6, 2023, after a long illness. Hellmuth designed dozens of award-winning buildings across the globe, including the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company Headquarters and the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi.

Contractors | Apr 10, 2023

What makes prefabrication work? Factors every construction project should consider

There are many factors requiring careful consideration when determining whether a project is a good fit for prefabrication. JE Dunn’s Brian Burkett breaks down the most important considerations.

Mixed-Use | Apr 7, 2023

New Nashville mixed-use high-rise features curved, stepped massing and wellness focus

Construction recently started on 5 City Blvd, a new 15-story office and mixed-use building in Nashville, Tenn. Located on a uniquely shaped site, the 730,000-sf structure features curved, stepped massing and amenities with a focus on wellness.

Smart Buildings | Apr 7, 2023

Carnegie Mellon University's research on advanced building sensors provokes heated controversy

A research project to test next-generation building sensors at Carnegie Mellon University provoked intense debate over the privacy implications of widespread deployment of the devices in a new 90,000-sf building. The light-switch-size devices, capable of measuring 12 types of data including motion and sound, were mounted in more than 300 locations throughout the building.

Affordable Housing | Apr 7, 2023

Florida’s affordable housing law expected to fuel multifamily residential projects

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently signed into law affordable housing legislation that includes $711 million for housing programs and tax breaks for developers. The new law will supersede local governments’ zoning, density, and height requirements.

Energy Efficiency | Apr 7, 2023

Department of Energy makes $1 billion available for states, local governments to upgrade building codes

The U.S. Department of Energy is offering funding to help state and local governments upgrade their building codes to boost energy efficiency. The funding will support improved building codes that reduce carbon emissions and improve energy efficiency, according to DOE.