When the 456-meter-tall Kunming Junfa Dongfeng Square tower opens in Kunming City, China, in mid-2017, it will stand as one of the world’s tallest naturally ventilated buildings. Roughly three-quarters of the tower’s 100 floors—the entire office portion of the mixed-use program—will be conditioned, at least partially, through buoyancy-driven natural ventilation.

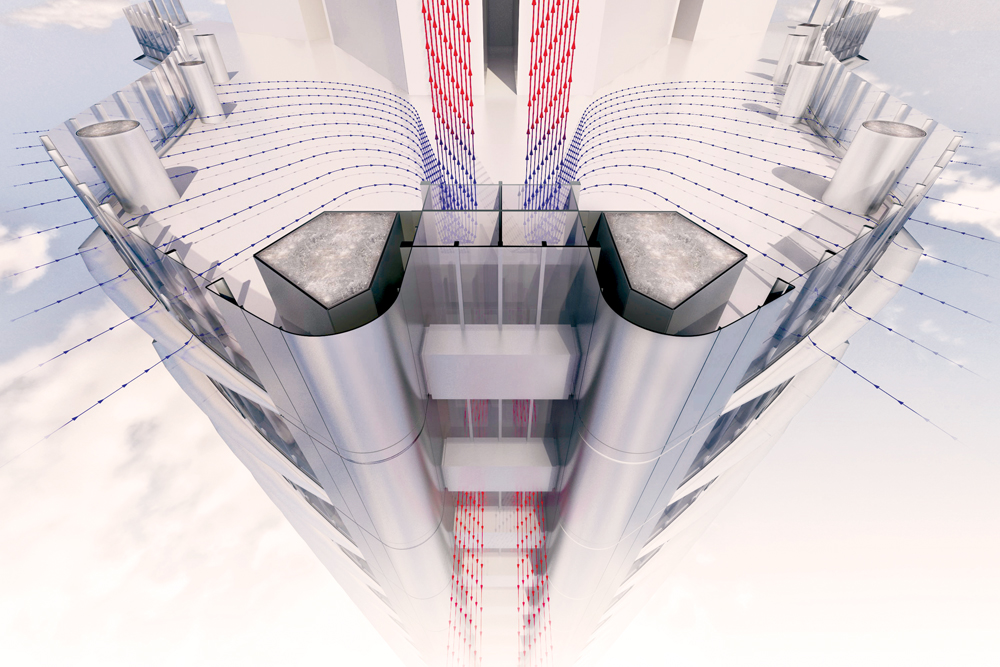

Using the basic principles of stack effect—the movement of air in and out of buildings based on air buoyancy—cool air will be drawn through the façade and funneled into the open-plan offices, through the ceiling plenum, and into a series of six-story “eco-chimneys,” where it will be exhausted. By utilizing the region’s temperate climate for “free” cooling and ventilation (no mechanical fans are required to move the air), the design team, led by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, expects to slash the building’s overall energy use by at least 13%.

“That’s just from the natural ventilation component,” says Stephen Ray, PhD, a Mechanical Engineer with SOM. “In the past, stack effect has been treated as a foe in tall building design. We’re harnessing these forces to improve building performance.”

The Kunming tower is among a handful of recent projects where SOM design teams are using the power of what the firm calls “passive dynamics” to provide free cooling and ventilation in buildings. Passive dynamics entails a number of design techniques and theories that share a common trait: the utilization of naturally occurring phenomena to reduce energy consumption and improve the indoor environment.

Passive Dynamics: 5 ways to uses natural air movement

1. Stack effect, or reversed stack effect, results from air buoyancy. Buoyancy occurs due to a difference in indoor-to-outdoor air density resulting from temperature and moisture differences. Unlike wind, this air movement is relatively stable with regard to temperature and is predictable for use in natural ventilation as well as power generation through a solar tower.

2. Wind towers, or wind catchers, are a traditional architectural element (mainly in residential construction) whose function is to catch cooler breezes that often prevail at a higher level above the ground and direct them into the interior living spaces.

3. Geothermal chambers use air movement that can form in cooler chambers below grade, where soil temperatures can be pretty stable. The earth’s cooler temperature can be used to cool air and creates air motion.

4. Double-wall façades or double-ventilated façades utilize the heat buildup created by solar shades to generate a stack effect inside the cavity. These façades “trap” the solar heat inside the cavity and create a “mote” to prevent direct infiltration and contaminants from entering the building.

5. Induced air movement occurs when the wind blows, inducing air to move along with it. While this inducement of air motion has been utilized in active HVAC devices similar to induction air units and chilled beams, it can also be utilized as a force for passive design. Vertical upward air movement will be created when wind blows across a horizontal plane to help exhaust and natural ventilation.

Design strategies range from more common approaches, such as stack-effect-driven natural ventilation, double-wall façades, and thermal mass, to more unusual strategies, such as wind towers and geothermal chambers.

Most of these design concepts have been applied for years—thousands of years in the case of the wind tower, or wind catcher, from ancient Persian architecture—but with today’s advanced modeling and simulation tools and knowledge of building science, firms like SOM are able to apply them much more effectively, confidently, and on a grander scale.

“These forces are there whether people choose to use them or not,” says Luke Leung, PE, LEED Fellow, SOM’s Director of Sustainable Engineering. “By harnessing them, we can see a tremendous reduction in energy use and increase in occupant comfort—and create buildings that are more sustainable overall.”

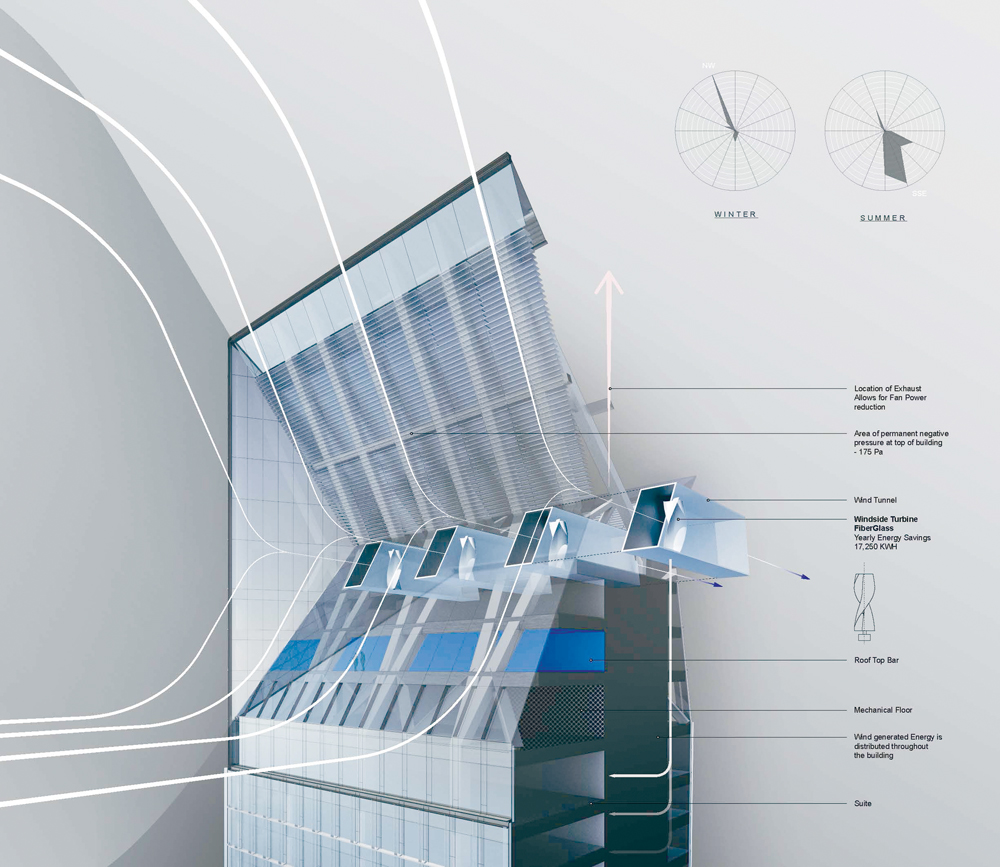

Leung points to the firm’s 324-meter-tall Greentown Center Tower in Qingdao, China, which is topped with a sail-inspired crown that is designed to draw air into the topmost portion of the building to create negative pressure at the roof level. This negative pressure pulls exhaust air up and out of the tower, greatly reducing the need for mechanical fans.

“In terms of toilet exhaust alone, the annual savings are 17,000 kilowatt hours by using passive dynamics as a natural fan in the building,” says Leung. “Typically, you would use a fan to create the pressure differential to exhaust air. What we’re doing here is using the wind directly to create that pressure differential.”

The Greentown Center Tower will also use the air movement to generate power. Four ducted vertical-axis wind turbines in the crown are expected to yield 322 mWh per year, offering a 10-year payback for the building’s owner. Operable windows throughout the tower permit natural ventilation, further reducing the mechanical system’s cooling loads.

LESSONS FROM NATURAL VENTILATION PROJECTS

“As an industry, we’re still learning about passive dynamics,” says Ray. “How can we most effectively harness stack effect in buildings? When using natural ventilation, what kind of Coanda effect (the tendency of a fluid jet to be attracted to a nearby surface, after Romanian aerodynamics expert Henri Coanda) should we expect based on the design?”

SOM’s Leung and Ray offer some lessons from the firm’s recent work on natural ventilation:

1. Be prepared to deal with air contaminants. Outside air is not always as healthy as indoor air. More than 90% of Europeans (according to a 2014 World Health Organization report) and 42% of Americans (says the American Lung Association) live in areas where the air is deemed unhealthy. SOM’s advice: measure both the indoor and outdoor air quality to ensure outdoor air is acceptable before opening any natural ventilation devices.

2. Not every climate is right for natural ventilation. Natural ventilation works best in climates where relatively healthy outdoor air is within an acceptable thermal range cooler than indoor air. While ASHRAE and international standards offer “adaptive comfort” to achieve comfort in humid climates through natural ventilation, “adaptive comfort” is based on natural ventilated buildings with no air-conditioning. Care must be taken when a building is air-conditioned. SOM’s take: try to use natural ventilation during transitional seasons.

The SOM-designed Greentown Center Tower in Qingdao, China, is topped with a sail-inspired crown that is designed to draw air into the topmost portion of the building to create negative pressure at the roof level. This negative pressure draws exhaust air up and out of the tower, greatly reducing the need for mechanical fans. The building will use the air movement to generate power via four ducted vertical-axis wind turbines in the crown.

3. Be aware of design elements that can hinder performance. It’s important to understand how much pressure the wind carries, and how far it has to travel. Design should be based on the power of the available wind; design all components not to exceed the available power. Otherwise, the design may not have enough power to drive the air movement.

4. Use the building form to enhance performance. A building’s shape can be your friend. It can accelerate the wind—for example, by using openings or obstacles to streamline air movement, or capturing the induced effect for air movement as a “fan”—or it can be used to change wind direction.

5. Air movement for natural ventilation can come from multiple sources. Wind-driven outside air is not the only source of air movement for natural ventilation. Air will move due to pressure or temperature differences. Stack (or reversed stack) effect is often a more stable and powerful element to move air than wind. Air movement can also be formed by pressure differences between higher and lower elevations.

Related Stories

| Feb 11, 2011

RS Means Cost Comparison Chart: Office Buildings

This month's RS Means Cost Comparison Chart focuses on office building construction.

| Feb 11, 2011

Sustainable features on the bill for dual-building performing arts center at Soka University of America

The $73 million Soka University of America’s new performing arts center and academic complex recently opened on the school’s Aliso Viejo, Calif., campus. McCarthy Building Companies and Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architects collaborated on the two-building project. One is a three-story, 47,836-sf facility with a grand reception lobby, a 1,200-seat auditorium, and supports spaces. The other is a four-story, 48,974-sf facility with 11 classrooms, 29 faculty offices, a 150-seat black box theater, rehearsal/dance studio, and support spaces. The project, which has a green roof, solar panels, operable windows, and sun-shading devices, is going for LEED Silver.

| Feb 11, 2011

BIM-enabled Texas church complex can broadcast services in high-def

After two years of design and construction, members of the Gateway Church in Southland, Texas, were able to attend services in their new 4,000-seat facility in late 2010. Located on a 180-acre site, the 205,000-sf complex has six auditoriums, including a massive 200,000-sf Worship Center, complete with catwalks, top-end audio and video system, and high-definition broadcast capabilities. BIM played a significant role in the building’s design and construction. Balfour Beatty Construction and Beck Architecture formed the nucleus of the Building Team.

| Feb 11, 2011

Kentucky’s first green adaptive reuse project earns Platinum

(FER) studio, Inglewood, Calif., converted a 115-year-old former dry goods store in Louisville, Ky., into a 10,175-sf mixed-use commercial building earned LEED Platinum and holds the distinction of being the state’s first adaptive reuse project to earn any LEED rating. The facility, located in the East Market District, houses a gallery, event space, offices, conference space, and a restaurant. Sustainable elements that helped the building reach its top LEED rating include xeriscaping, a green roof, rainwater collection and reuse, 12 geothermal wells, 81 solar panels, a 1,100-gallon ice storage system (off-grid energy efficiency is 68%) and the reuse and recycling of construction materials. Local firm Peters Construction served as GC.

| Feb 11, 2011

Former Richardson Romanesque hotel now houses books, not beds

The Piqua (Ohio) Public Library was once a late 19th-century hotel that sat vacant and deteriorating for years before a $12.3 million adaptive reuse project revitalized the 1891 building. The design team of PSA-Dewberry, MKC Associates, and historic preservation specialist Jeff Wray Associates collaborated on the restoration of the 80,000-sf Richardson Romanesque building, once known as the Fort Piqua Hotel. The team restored a mezzanine above the lobby and repaired historic windows, skylight, massive fireplace, and other historic details. The basement, with its low ceiling and stacked stone walls, was turned into a castle-like children’s center. The Piqua Historical Museum is also located within the building.

| Feb 11, 2011

Justice center on Fall River harbor serves up daylight, sustainable elements, including eucalyptus millwork

Located on historic South Main Street in Fall River, Mass., the Fall River Justice Center opened last fall to serve as the city’s Superior and District Courts building. The $85 million facility was designed by Boston-based Finegold Alexander + Associates Inc., with Dimeo Construction as CM and Arup as MEP. The 154,000-sf courthouse contains nine courtrooms, a law library, and a detention area. Most of the floors have the same ceiling height, which will makes them easier to reconfigure in the future as space needs change. Designed to achieve LEED Silver, the facility’s elliptical design offers abundant natural daylight and views of the harbor. Renewable eucalyptus millwork is one of the sustainable features.

| Feb 11, 2011

Research facility separates but also connects lab spaces

California State University, Northridge, consolidated its graduate and undergraduate biology and mathematics programs into one 90,000-sf research facility. Architect of record Cannon Design worked on the new Chaparral Hall, creating a four-story facility with two distinct spaces that separate research and teaching areas; these are linked by faculty offices to create collaborative spaces. The building houses wet research, teaching, and computational research labs, a 5,000-sf vivarium, classrooms, and administrative offices. A four-story outdoor lobby and plaza and an outdoor staircase provide orientation. A covered walkway links the new facility with the existing science complex. Saiful/Bouquet served as structural engineer, Bard, Rao + Athanas Consulting Engineers served as MEP, and Research Facilities Design was laboratory consultant.

| Feb 11, 2011

A feast of dining options at University of Colorado community center, but hold the buffalo stew

The University of Colorado, Boulder, cooked up something different with its new $84.4 million Center for Community building, whose 900-seat foodservice area consists of 12 micro-restaurants, each with its own food options and décor. Centerbrook Architects of Connecticut collaborated with Denver’s Davis Partnership Architects and foodservice designer Baker Group of Grand Rapids, Mich., on the 323,000-sf facility, which also includes space for a career center, international education, and counseling and psychological services. Exterior walls of rough-hewn, variegated sandstone and a terra cotta roof help the new facility blend with existing campus buildings. Target: LEED Gold.

| Feb 11, 2011

Chicago high-rise mixes condos with classrooms for Art Institute students

The Legacy at Millennium Park is a 72-story, mixed-use complex that rises high above Chicago’s Michigan Avenue. The glass tower, designed by Solomon Cordwell Buenz, is mostly residential, but also includes 41,000 sf of classroom space for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and another 7,400 sf of retail space. The building’s 355 one-, two-, three-, and four-bedroom condominiums range from 875 sf to 9,300 sf, and there are seven levels of parking. Sky patios on the 15th, 42nd, and 60th floors give owners outdoor access and views of Lake Michigan.

| Feb 11, 2011

Iowa surgery center addresses both inpatient and outpatient care

The 12,000-person community of Carroll, Iowa, has a new $28 million surgery center to provide both inpatient and outpatient care. Minneapolis-based healthcare design firm Horty Elving headed up the four-story, 120,000-sf project for St. Anthony’s Regional Hospital. The center’s layout is based on a circular process flow, and includes four 800-sf operating rooms with poured rubber floors to reduce leg fatigue for surgeons and support staff, two substerile rooms between each pair of operating rooms, and two endoscopy rooms adjacent to the outpatient prep and recovery rooms. Recovery rooms are clustered in groups of four. The large family lounge (left) has expansive windows with views of the countryside, and television monitors that display coded information on patient status so loved ones can follow a patient’s progress.