Pediatric hospitals face many of the same concerns as their adult counterparts. The most consistent concern is change. Nationally, inpatient bed demand is declining, outpatient visits are soaring, and there is a higher level of focus on prevention and reduced readmissions.

The solution is not as simple as swapping inpatient space with outpatient care to meet the shifting demand. Many facilities have been operating 40% or more of their beds as semiprivates and—driven by reimbursement incentives for patient satisfaction and consumers’ penchant for choosing care based on public performance scores—hospital owners have no choice but to invest their limited capital dollars in new or renovated space to achieve 100% private-bed models.

In certificate of need (CON) states, owners are reluctant to reduce total bed counts due to the uncertainty in future bed demand. To effectively operate within this changing environment, owners look to the healthcare design and construction industry for creative facility solutions that offer highly flexible environments that promote healing.

Flexible Spaces, for Toddlers and Teens

Flexibility is key in helping owners address rapidly changing demands. While this is also true in adult care, children’s hospitals face a greater challenge due to the drastic difference in their patient dynamic. Caring for a patient in the NICU is significantly different than caring for a 16-year-old. Add the fact that pediatric inpatient volumes are sporadic at best, and you have an operational challenge in achieving ideal staff-to-patient ratios.

Children’s Medical Center Dallas has addressed uncertainty by designing patient rooms with a universal care model so they can be converted to ICU rooms with no construction impact. This will allow the hospital to flex with future trends.

Another way pediatric facilities are creating greater flexibility is by developing inpatient units that are more appropriate for all ages instead of just focusing on babies. In doing this, not only does the physical environment need to be highly adaptable to accommodate pediatric patients—i.e., adjustable sink heights, grab bars, and so on—but the design aesthetic must also evolve. Interiors need to move away from cutesy baby motifs to ones more appropriate for a wider age spectrum, from toddlers to teens.

The rooftop garden provides a healing respite in an urban setting and is part of the LEED Gold-certified Benjamin Russell Hospital for Children’s environmentally friendly design.

Children’s of Alabama (COA) in Birmingham, Ala., was faced with these issues before opening its new facility, the Benjamin Russell Hospital for Children, in August 2013. To address these concerns, significant time was spent planning the design and “theme” for each floor. Wall surrounds and digital graphics portray wildlife, sports, nature, transportation, and other easy-to-remember themes. These were carried out in the hallways, common areas, and patient rooms. This strategy not only created a more inviting and comforting space for patients of all ages but also helped in the hospital’s wayfinding efforts. While a parent or child may not remember their room number, they would remember that they are in the “sports” tower, on the baseball floor, with a glove and ball by their room.

Tailoring the Healing Environment

Pediatric hospitals are not alone in their journey to becoming more patient-centered and family-focused, but the creative environments found in today’s children’s facilities puts them light years ahead of their adult-hospital peers. By engaging patients and their families in the design process, leaders are identifying what is most important for comfort and satisfaction.

Customization is increasingly popular. For example, integrating LED lights can enable patients to select their own wall and ceiling colors, giving them ultimate control over the look of their rooms. To further accommodate a broad age span, each patient room at COA is outfitted with an Xbox game console. These systems are tied into the hospital’s Patient Entertainment and Information System to provide an added layer of comfort. Patients, and more importantly their parents, are able to use the systems to research an illness, identify hospital services, and communicate with staff. One patient even commented, “Honestly, the hospital felt more like a hotel than a hospital.”

For larger pediatric units, playrooms for toddlers and teen rooms equipped with Wii stations offer on-unit destinations that allow patients a respite, inviting them to explore and to meet other children. Rooftop gardens are becoming more popular, making a bit of the outdoors accessible. COA’s rooftop garden, near the NICU, is designed to be a healing garden. The Building Team situated the “Quarterback” (West) Tower so that the end caps on each floor overlook Regions Field, home of the Birmingham Barons baseball team. On Friday nights, children can congregate at the end of the hall or in the garden to enjoy the weekly fireworks display.

Family friendly themed wall-surrounds, vibrant colors, and a bold room numbering system combine with a wavy “blue river” pattern in the flooring at the Benjamin Russell Hospital for Children help patients and families with wayfinding.

Dedicated family space has also become very popular for children’s hospitals. “Family” zones, in patient rooms and in common areas, are designed to keep family members closer to their children, allowing for some privacy and comfort. The concept focuses on the family’s interaction with the hospital staff and their child to ensure a desirable flow. At design meetings, nursing staff often stress the importance of having a specific zone to accommodate parents within the patient room. In some instances, patient floors have been fitted with a family waiting area equipped with a kitchenette. This feature allows families to feel more at home during lengthy stays by giving them access to a refrigerator, sink, and microwave. Guest laundry areas may also be located on the unit for parent use.

Staff Space: Allow for Decompression

The distinctiveness of a children’s hospital transcends facility design. Staff play a critical role in the care and comfort of the children and their families. Staff often use the term “frequent flyers” to describe parents and children who must come to the hospital regularly for care. Even the security officers stationed at the door become very involved in the lives of these families and children. Staff at all levels, not just the caregivers, get to know the families and will go the extra mile to make their experience as pleasant and stress-free as possible.

Because the work is demanding, Building Teams should give special attention to the caregiver and staff areas of a pediatric facility. Make opportunities for staff to be “offstage” by providing inviting break areas, dining facilities, and outdoor spaces. These features enable staff to decompress during their workday, resulting in improved clinical performance when staff members are “onstage” caring for kids.

Hospitals are not typically envisioned as warm and inviting places. However, changes in design and care standards are creating spaces that provide patients and their families with much more comfort. From the outside “curb appeal” to the internal operations and systems, children’s hospitals are striving to achieve low-stress environments that aid in the healing and wellness of our smallest patients.

Staff spaces are open and comfortable, providing easy access to patient rooms. Glass end caps and sub-waiting areas at the end of each hallway provide expansive views of the city and Birmingham’s Regions Field at Children’s of Alabama.

Spacious accommodations, warm aesthetics, and stimulating amenities aim to promote a relaxing environment for patients and their families throughout the healing process at Children’s Medical Center.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

The authors of this article are affiliated with healthcare consulting firm CBRE Healthcare, based in Richmond, Va. They are Lora Schwartz, AIA, LEED AP, Principal; Stephen Powell, Consultant; Brad Durham, MBA, Principal; Magnus Nilsson, RA, Senior Consultant; Steven Donnelly, Vice President; and Curtis Skolnick, MHA, Vice President.

Related Stories

| Apr 12, 2011

American Institute of Architects announces Guide for Sustainable Projects

AIA Guide for Sustainable Projects to provide design and construction industries with roadmap for working on sustainable projects.

| Apr 11, 2011

Wind turbines to generate power for new UNT football stadium

The University of North Texas has received a $2 million grant from the State Energy Conservation Office to install three wind turbines that will feed the electrical grid and provide power to UNT’s new football stadium.

| Apr 8, 2011

SHW Group appoints Marjorie K. Simmons as CEO

Chairman of the Board Marjorie K. Simmons assumes CEO position, making SHW Group the only firm in the AIA Large Firm Roundtable to appoint a woman to this leadership position

| Apr 5, 2011

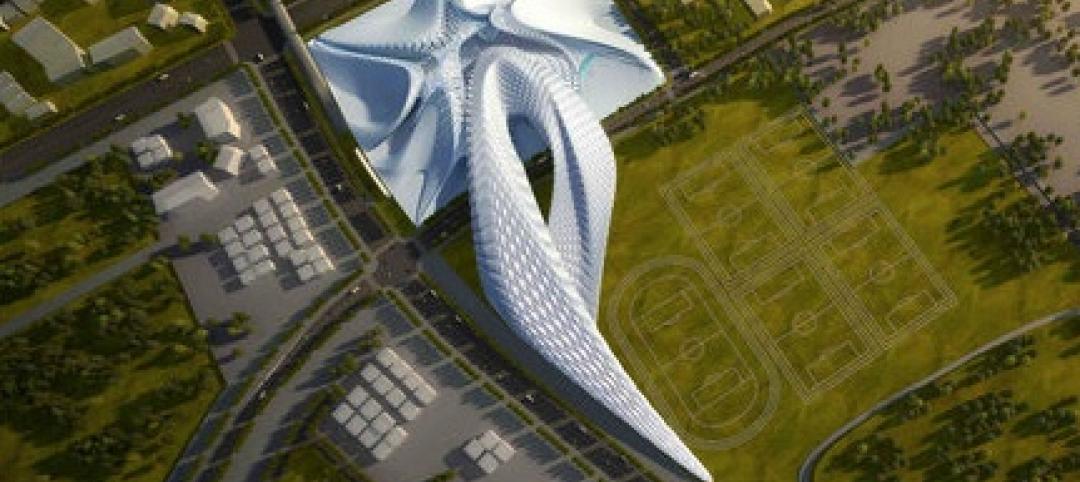

Zaha Hadid’s civic center design divides California city

Architect Zaha Hadid is in high demand these days, designing projects in Hong Kong, Milan, and Seoul, not to mention the London Aquatics Center, the swimming arena for the 2012 Olympics. But one of the firm’s smaller clients, the city of Elk Grove, Calif., recently conjured far different kinds of aquatic life when members of the City Council and the public chose words like “squid,” “octopus,” and “starfish” to describe the latest renderings for a proposed civic center.

| Apr 5, 2011

Are architects falling behind on BIM?

A study by the National Building Specification arm of RIBA Enterprises showed that 43% of architects and others in the industry had still not heard of BIM, let alone started using it. It also found that of the 13% of respondents who were using BIM only a third thought they would be using it for most of their projects in a year’s time.