The COVID-19 pandemic has strained the resources and exposed the vulnerabilities of many hospitals as they confront the most serious global health crisis in over a century. Controlling the spread of this highly contagious virus while treating infected patients and protecting staff is fundamental to the mission of every healthcare facility.

Yet infection control remains one of the most challenging aspects of hospital operations.

Each year, healthcare-associated infections impact 1.7 million patients at U.S. acute care facilities, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths and costing the healthcare system billions of dollars.1

As hospitals and health systems assess their existing infrastructure and plan for the future, they can learn valuable lessons from the infection control strategies implemented at high-containment research labs. These secure research environments are designed and built with the primary function of protecting individuals and communities from microorganisms, infectious agents and other toxins.

McCarthy recently conducted a study of healthcare providers, architects and engineers to learn about their response to COVID-19. We discovered that as many healthcare providers consider implementing enhanced infection control strategies, they are also assessing the construction implications for existing and new facilities. They know it is not practical — nor economically feasible — to implement all the intricate safety and security strategies of a high-containment lab. As a result, they are consulting proven BSL-4 builders for valuable guidance on the design and construction of future healthcare environments.

Having built more than 25 percent of the nation’s BSL-4 labs in the last 20 years while earning a consistent ranking as one of America’s top healthcare builders, McCarthy is helping clients identify effective and value-driven infection control solutions for their facilities.

Here are five core principles from high-containment labs that directly support the current infection control priorities of hospitals and other healthcare facilities:

1. Design and build flexible infrastructure for responding to future crises.

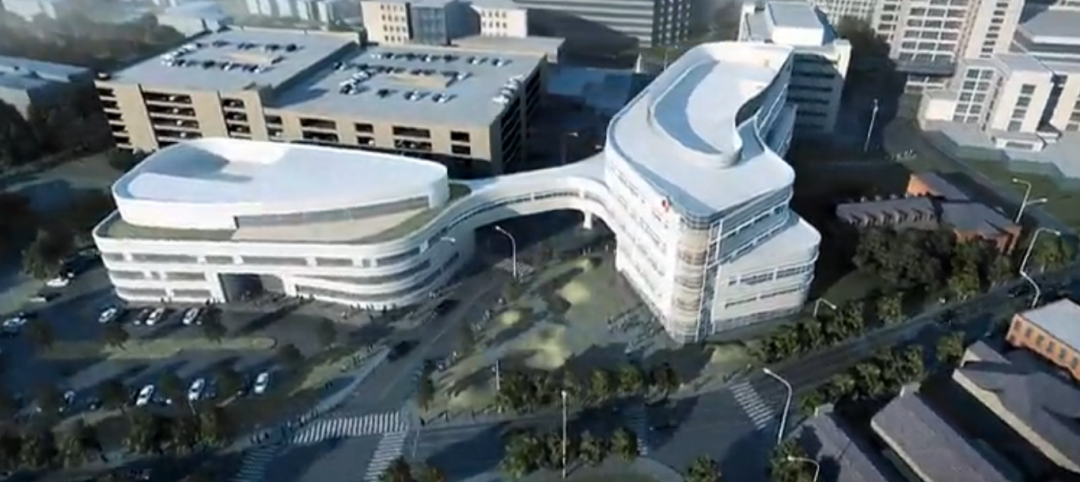

Hospitals of the future will be expected to quickly adapt to accommodate patient surges resulting from unforeseen events such as a pandemic or natural disaster. Public spaces may need to be converted into triage or patient care spaces during an emergency. For example, at the new Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, Calif., the attached parking garage and interior public spaces were designed and built with the capability of transforming into triage spaces if necessary.

Similarly, primary patient care spaces such as an ICU or surgical area may need to temporarily function as a negative pressure isolation room to contain airborne contaminants. Only 2 to 4 percent of all U.S. hospital rooms are currently equipped for negative pressure, as these spaces must be airtight and have a dedicated exhaust system and HEPA filters.3

A skilled builder can help you overcome the numerous design and construction challenges of creating these isolation spaces and the associated maintenance considerations. This includes the need to certify HEPA filters annually and replace them frequently to prevent buildup of dirt and contaminants.

2. Separate and safely manage waste streams.

U.S. hospitals produce more than 5 million tons of medical waste each year.4 About 15 percent of this waste is considered hazardous and must be handled and disposed of according to strict local laws and guidelines. In a BSL-4 lab, all waste — including filtered air, water, effluent and trash — must be decontaminated before it can leave the facility.

By using the knowledge gained constructing BSL-4 facilities, the right partner can work with you to develop new infectious waste management practices separate from the existing hospital waste management system. This includes the establishment of a dedicated process to collect, capture, decontaminate and dispose of and/or incinerate all solid and liquid waste. It may also involve installation of an effluent decontamination system to neutralize all liquid waste materials before they are released into the environment.

3. Develop new strategies and protocols to protect healthcare workers.

In both lab and hospital environments, the greatest potential risk is not the building, mechanical systems or equipment. It is the people who inhabit the space. Anytime the human element is involved, it increases the risk of noncompliance with operational policies, procedures and protocols. And once there’s a breach in protocol, the probability of cross-contamination rises exponentially.

While it’s impossible to eliminate all potential risks for hospital workers, BSL-4 builders know creating spaces and systems that reduce the likelihood of cross-contamination is possible. These strategies include establishing secure, restricted areas for gowning and accessing other PPE, investing in touchless sinks and lighting, and installing self-closing, lockable doors.

McCarthy is currently working with the Flad / Page partnership to design and construct the CDC’s new High Containment Continuity Laboratory in Atlanta. The building will be a Biosafety Level-4 (BSL-4) facility, a designation reserved for the highest level of biological safety, and it will accommodate approximately 80 laboratory researchers.

High-containment labs are also designed to accommodate employee movement and flow strategies. For example, many labs are designed with a two-person rule in mind; each researcher has a colleague present to assist if something goes wrong. High-containment areas also have built-in sightlines to maintain visual connectivity from outside. These same design principles can be implemented in new or existing hospitals to enhance infection control and reduce risk for staff and patients.

4. Rethink patient flows to stop disease at the door.

From check-in to follow-up, the entire healthcare experience must become more automated and efficient. Some hospitals are experimenting with telemedicine, remote triaging and a zero-contact intake process using robotics and geolocation to ensure admissions are made with as little contact with staff and other patients as possible.5

Others are considering the elimination of traditional emergency room waiting areas and designating separate entrances and waiting spaces for suspected infectious or high-risk patients. For example, McCarthy is researching alternatives like RFID (Radio-Frequency Identification) technology for tracking people and materials as they enter and move throughout BSL-4 facilities. In hospitals, the same technology could track and alert patients and their families as they’re waiting, and as part of a comprehensive wayfinding system would be capable of efficiently directing them to the right location for treatment.

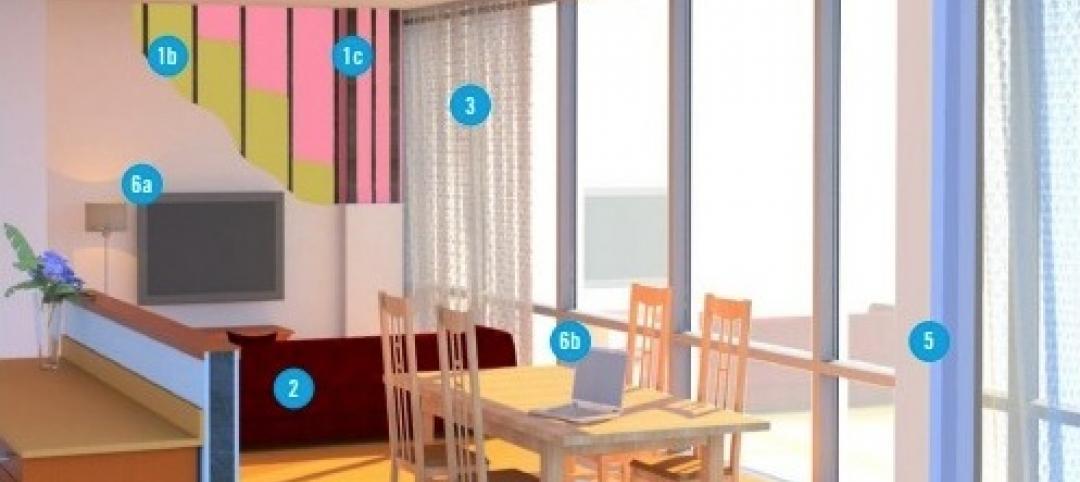

5. Reassure patients and visitors they’re in a safe environment.

In recent years, the healthcare industry has focused on hospitality and patient-centered design, which has resulted in many beautiful, state-of-the-art facilities. As hospitals consider how to adapt their buildings and spaces to address current realities and future code changes, they need to consider the optics of those decisions. Will patients and visitors notice the alterations, and if so, will the strategies instill confidence and peace of mind that they are in a secure, protected environment? This extends to everything from signage to physical barriers to visible ventilation systems. In the future, designers, builders and owners will need to expand their definition of patient-centered to ensure people using the system feel safe.

Using BSL-4 construction principles to modify how future healthcare facilities are designed, built, operated and maintained can help control the spread of infectious disease and reduce the negative impact of future outbreaks. At the same time, these changes can enhance the overall perceptions and experiences of patients, staff and visitors even when there is no crisis.

Building for the Future

The COVID-19 pandemic has quickly transformed how healthcare providers must assess and address infection control within their facilities. Once a secondary consideration, infection control is now a top safety priority shaping the future of every healthcare facility in America.

The good news is builders like McCarthy — with a long history of microbiological and biomedical laboratory and healthcare construction experience — are developing new, cost-efficient ways to apply Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) infection control standards and strategies to new and existing hospitals.

In new facilities, we apply years of highly technical BSL-4 construction expertise to build extremely flexible and safe environments. In existing facilities, we integrate innovative BSL-4 infection control standards without disrupting the ongoing patient experience. We’ll continue to leverage our knowledge and expertise to help shape the most effective healthcare facilities that will continue to serve our communities.

1 www.beckershospitalreview.com

2 www.labmanager.com

3 www.fastcompany.com

4 www.practicegreenhealth.org

5 www.wsj.com

Related Stories

| Oct 30, 2014

CannonDesign releases guide for specifying flooring in healthcare settings

The new report, "Flooring Applications in Healthcare Settings," compares and contrasts different flooring types in the context of parameters such as health and safety impact, design and operational issues, environmental considerations, economics, and product options.

| Oct 30, 2014

Perkins Eastman and Lee, Burkhart, Liu to merge practices

The merger will significantly build upon the established practices—particularly healthcare—of both firms and diversify their combined expertise, particularly on the West Coast.

| Oct 21, 2014

Passive House concept gains momentum in apartment design

Passive House, an ultra-efficient building standard that originated in Germany, has been used for single-family homes since its inception in 1990. Only recently has the concept made its way into the U.S. commercial buildings market.

| Oct 21, 2014

Hartford Hospital plans $150 million expansion for Bone and Joint Institute

The bright-white structures will feature a curvilinear form, mimicking bones and ligament.

| Oct 16, 2014

Perkins+Will white paper examines alternatives to flame retardant building materials

The white paper includes a list of 193 flame retardants, including 29 discovered in building and household products, 50 found in the indoor environment, and 33 in human blood, milk, and tissues.

| Oct 15, 2014

Harvard launches ‘design-centric’ center for green buildings and cities

The impetus behind Harvard's Center for Green Buildings and Cities is what the design school’s dean, Mohsen Mostafavi, describes as a “rapidly urbanizing global economy,” in which cities are building new structures “on a massive scale.”

| Oct 13, 2014

Debunking the 5 myths of health data and sustainable design

The path to more extensive use of health data in green building is blocked by certain myths that have to be debunked before such data can be successfully incorporated into the project delivery process.

| Oct 12, 2014

AIA 2030 commitment: Five years on, are we any closer to net-zero?

This year marks the fifth anniversary of the American Institute of Architects’ effort to have architecture firms voluntarily pledge net-zero energy design for all their buildings by 2030.

| Oct 8, 2014

Massive ‘healthcare village’ in Nevada touted as world’s largest healthcare project

The $1.2 billion Union Village project is expected to create 12,000 permanent jobs when completed by 2024.

| Oct 3, 2014

Designing for women's health: Helping patients survive and thrive

In their quest for total wellness, women today are more savvy healthcare consumers than ever before. They expect personalized, top-notch clinical care with seamless coordination at a reasonable cost, and in a convenient location. Is that too much to ask?