The relationships between buildings and machines have always defined the fields of design and construction. More than 2,000 years ago, in the first treatise on architecture, Vitruvius dedicated all of the final volume to machines. Since then, arguably the entire history of construction has centered on the movement away from handicraft toward progressive degrees of mechanization. Today, mechanization, the replacement of hand labor, is increasingly giving way to automation, the replacement of human labor altogether.

Below are four fundamental relationships between buildings and machines. As automation becomes more prominent, it is changing these relationships dramatically.

Machines in Buildings

Over the past century or two, new mechanisms have fundamentally redefined the possibilities of buildings. After Elisha Otis invented the safety elevator in 1852, buildings could climb well beyond a comfortable walk-up height, and the skyscraper was born.

In 1902, Willis Carrier introduced modern air conditioning, which allowed floor plates to get deeper (spurring a century of energy hogging). The bimetallic thermostat, an example of automation dating from the 1880s, long has been a staple in homes and offices everywhere. Building automation systems (BAS) apply this concept systemwide, with internal feedback adjusting HVAC and lighting to improve comfort, security, energy consumption, maintenance, and operating costs.

The Internet of Things (IoT) connects computers embedded in everyday objects, including buildings, to expand these feedback loops beyond the immediate building to the entire world. Over the next few years alone, instances of IoT are expected to double in commercial real estate. Buildings are coming to be defined less as static objects and more as completely fluid environments.

Machines for Building

Ancient structures were assembled with a few simple tools, and the oldest may have used none at all. Possibly the earliest known “constructions,” during the Stone Age, were made of Mammoth bones lashed together to form huts. With the agricultural revolution, communities became less nomadic, and buildings became less portable, leading to heavier construction and the need for more powerful tools.

The industrial revolution catapulted whole industries and economies with mass-produced timber and steel. The history of construction since then has been propelled by leveraging more and more force, and today gigantic machines for digging and lifting dominate large construction sites.

But emerging automated techniques could return building fabrication to its origins in lightweight assembly methods. Homes are being 3D printed in 24 hours at a fraction of the expense of traditional construction. Bricklaying robots can assemble a wall at half the cost and 3-5 times the productivity. Soon, clouds of flying assembler drones could become the norm, making construction sites buzz and thrum like beehives or ant hills.

Buildings as Machines

“A house is a machine for living in,” Le Corbusier famously declared in 1929, and the mechanical metaphor became a foundational premise of modern architecture. Later, the machine aesthetic became more explicit. The Centre Pompidou in Paris (1977) wore its systems on its sleeve, the primary architectural expression coming from equipment, ductwork, and conveying systems.

But metaphor could soon become reality. Nanotechnology, originally proposed by Nobel physicist Richard Feynman half a century ago, manipulates individual atoms and molecules to build things—anything. Already, researchers have successfully experimented with nanotech in concrete and steel, strengthening materials and improving performance by adjusting automatically to offset stress and strain.

‘Buildings are coming to be defined less as static objects and more as

completely fluid environments.’ — Lance Hosey, FAIA, LEED Fellow, Gensler

Experts anticipate that within the next few decades, whole buildings could be fabricated using microscopic robots, which would join to make a cybernetic glue, eliminating traditional material constraints. Standard, irreducible components, such as the 2x4, the brick, and steel shapes, could be replaced by microscopic parts, and form, texture, color, and strength could be defined at the cellular level.

Orthogonal geometry, demanded for efficiency by standard frame construction, could disappear altogether. A century ago, Frank Lloyd Wright described “organic architecture” as “building the way nature builds.” Nanotech could finally bring this to fruition.

By modifying themselves over successive generations, ebbing and flowing in endless cycles of reproduction and adaptation, nano-assemblers could produce architecture through a process similar to genetic evolution—only faster—and therefore build exactly the way nature builds.

Buildings by and for Machines

In previous articles in this series, we’ve explored the implications of artificial intelligence. Futurist Ray Kurzweil predicts that machines will achieve human-level intelligence within a decade, and this will affect every industry, including our own.

If and when AI drives the entire process of design, construction, and operation, buildings could become exponentially smarter with resources, money, time, and performance, creating environments more engaging and comforting than we can imagine right now.

Yet, Kurzweil also anticipates that within a century we will concede that machines have legal and civil rights. Will self-aware buildings become as privileged as their inhabitants? How will our relationship with buildings change if we begin to see them as our equals? Machines could become more like us, but we could become more like them, as well.

Kurzweil is certain that artificial enhancements of the human body will become more common until we are more synthetic than organic. It will become possible to scan the mind and download it into more durable or flexible containers—such as buildings. Dwelling and dweller could become one and the same.

Lance Hosey, FAIA, LEED Fellow, is a Design Director with Gensler. His book, The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design, has been an Amazon #1 bestseller in the Sustainability & Green Design category.

Related Stories

Urban Planning | Dec 15, 2021

EV is the bridge to transit’s AV revolution—and now is the time to start building it

Thinking holistically about a technology-enabled customer experience will make transit a mode of choice for more people.

Designers / Specifiers / Landscape Architects | Nov 16, 2021

‘Desire paths’ and college campus design

If a campus is not as efficient as it could be, end users will use their feet to let designers know about it.

AEC Tech | Oct 25, 2021

Token Future: Will NFTs revolutionize the design industry?

How could non-fungible tokens (NFTs) change the way we value design? Woods Bagot architect Jet Geaghan weighs risk vs. reward in six compelling outcomes.

Sponsored | BD+C University Course | Oct 15, 2021

7 game-changing trends in structural engineering

Here are seven key areas where innovation in structural engineering is driving evolution.

AEC Tech Innovation | Oct 7, 2021

How tech informs design: A conversation with Mancini's Christian Giordano

Mancini's growth strategy includes developing tech tools that help clients appreciate its work.

AEC Tech | Oct 5, 2021

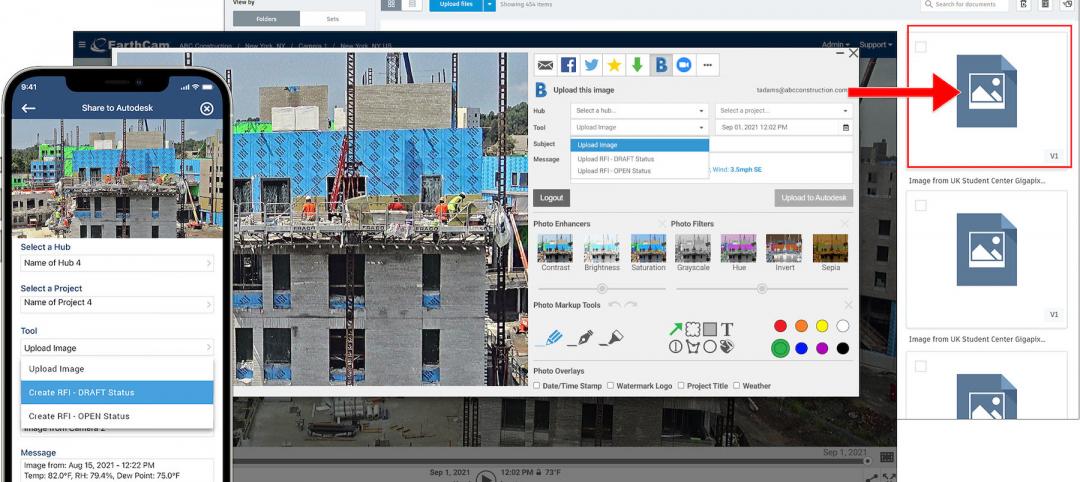

EarthCam Builds On its Connectivity with Autodesk Construction Cloud

Premiering new visual verification features for Autodesk Build and BIM 360

AEC Tech | Sep 21, 2021

A new webtool follows ConTech from incubation to application and beyond

MIT and JLL have created Tech Tracker to help real estate professionals see what’s hot now and what might be.

Architects | Aug 5, 2021

Lord Aeck Sargent's post-Katerra future, with LAS President Joe Greco

After three years under the ownership of Katerra, which closed its North American operations last May, the architecture firm Lord Aeck Sargent is re-establishing itself as an independent company, with an eye toward strengthening its eight practices and regional presence in the U.S.

Architects | Aug 5, 2021

Lord Aeck Sargent's post-Katerra future, with LAS President Joe Greco

After three years under the ownership of Katerra, which closed its North American operations last May, the architecture firm Lord Aeck Sargent is re-establishing itself as an independent company, with an eye toward strengthening its eight practices and regional presence in the U.S.

AEC Tech | Jul 14, 2021

Bjarke Ingels Group and UNStudio invest in SpaceForm, a virtual workspace for architects

Squint/Opera developed the platform in 2018.