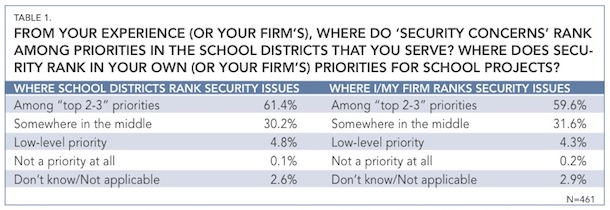

The great majority of architects, engineers, and contractors who responded to an exclusive Building Design+Construction “School Security Survey”—61.4%—ranked “security concerns” among the top two or three priorities for the school districts they serve. As one respondent put it, “School security has come to the forefront of our designs.”

The survey was conducted a month before the anniversary of the December 14, 2012, shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School, Newtown, Conn., where 20 children and six adults were killed by a lone gunman.

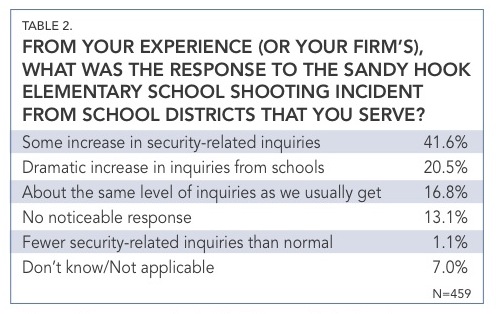

Only about one in five respondents (20.5%) said they experienced a rush of inquiries following the tragedy at the school. In response to Sandy Hook, AIA Iowa, Iowa Homeland Security, the State Fire Marshal, the Iowa Department of Education, and others formed the Iowa School Safety Coalition (http://www.iowaschoolsafety.org/) immediately after the event. “We publish periodic bulletins and we’re doing training on how to improve school safety,” said William M. Dikis, FAIA, NCARB, with Architectural Strategies, LLC, and the AIA Iowa representative on the coalition.

(Editor's Note: This article is the third in BD+C's five-part special report on security design for K-12 school projects. Read the full report.)

Herm Harms, AIA, an architect with Puetz Corp., said K-12 clients of his that had forestalled key security improvements to older buildings moved these improvements to top priority following Sandy Hook. “Even though money is tight, they’re still finding ways to make these upgrades,” he said.

The degree of concern about security among respondents and their professional firms closely parallels their perception of how school districts see the problem. Only a small percentage of respondents (<5%) said they view security as a low or nonexistent priority for themselves, their firms, or their school district clients.

The degree of concern about security among respondents and their professional firms closely parallels their perception of how school districts see the problem. Only a small percentage of respondents (<5%) said they view security as a low or nonexistent priority for themselves, their firms, or their school district clients.

Other respondents, however, said they’ve been plugging away on security for a long time. “We already have a security division that is very experienced and have made a priority of door security, upgrades of keying systems, and a door access system with surveillance cameras, remote release, visitor sign-in systems, ID badges, access controls with visitor cards, vision panels to the front entrance, time locks, and screening visitors for criminal records (with our police department),” said Fleur Duggan, AIA, LEED AP, Construction and ADA Manager, Fairfax County (Va.) Public Schools.

A tiny splinter of respondents (1.7%) said they have no worries about security in their schools. “We don’t have a security problem in our town,” said one. “Can’t happen here,” said another. David W. Myers, Senior Mechanical/Plumbing Designer at LaBella Associates, D.P.C., said most districts his firm works with have the situation under control: “The schools already have basic security measures in place and do not have the funding to upgrade further.”

Others said some school systems are constantly seeking security nirvana. “The districts we work with are continually pursuing security upgrades, both technological and building modifications.” Another was less sanguine: “They upgrade where they can with the budget they have.” Carol Ross Barney, FAIA, Principal of Chicago-based design firm Ross Barney Architects, said it’s a matter of priorities: “Our clients are more concerned about tornado storm protection than firearms.”

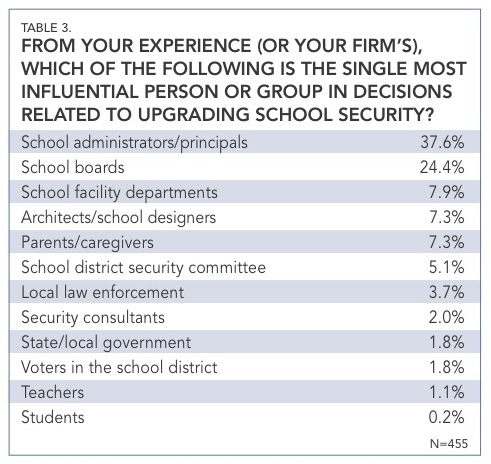

WHO REALLY GIVES THE GO-AHEAD FOR SECURITY IMPROVEMENTS?

It’s clear from Table 3 that school officials—not parents, voters, law enforcement agencies, or school designers—are the real decision makers when it comes to upgrading security systems in schools. But that doesn’t mean others shouldn’t have a say. “Best practices tend to include the security expert, school administration, and local law enforcement teamed to provide a system that protects the students and staff and serves the needs of first responders,” said Lance C. Mushung, AIA, NCARB, Architect/Senior Associate with SSOE Group.

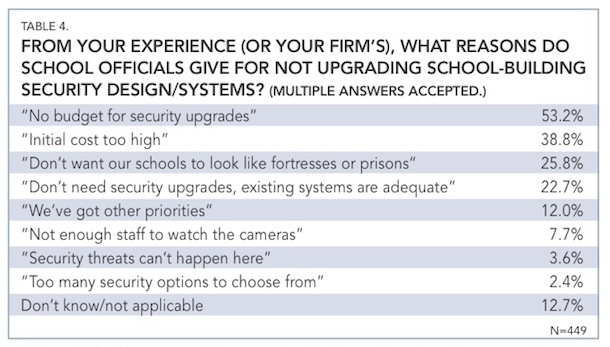

Still, as Table 4 shows, tight school district budgets, coupled with the belief that security upgrades cost too much, impede adoption of improvements. “Most schools upgrade where they can with the budget they have,” said one respondent. Even when upgrades get the green light, said another, “The final system is typically specified below the preferred system due to costs.”

Three of five respondents (62.1%) recorded at least some bump in inquiries from school districts following the December 14, 2012, shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary. A substantial group (29.9%) said there was either no heightened response, or that conditions were more or less business as usual.

Three of five respondents (62.1%) recorded at least some bump in inquiries from school districts following the December 14, 2012, shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary. A substantial group (29.9%) said there was either no heightened response, or that conditions were more or less business as usual.

“School security is a priority with parents, but not necessarily with taxpayers, even though they are often the same,” said Jim Princehorn, CPP, a Senior Security Advisor in Rochester, N.Y. “They want secure school buildings but do not realize that a K-12 school is very complex, with many entrances, many other entry points (loading docks, roof hatches, etc.), and many types of occupancy—clubs, sports, concerts, church organizations, Scout meetings—all of which complicate the planning of a secure facility. Often the access needs of one group affect the security planning of other sections of the building.”

One approach may be to avoid trying to bite the whole apple. “Security upgrades can be phased in,” said Doug Titus, CFM, an education security expert with manufacturer ASSA ABLOY Door Security Solutions. Schools can implement the highest-priority security upgrades first, he said, then phase less crucial improvements over time.

GETTING DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY—UPGRADING EXISTING SCHOOL BUILDINGS

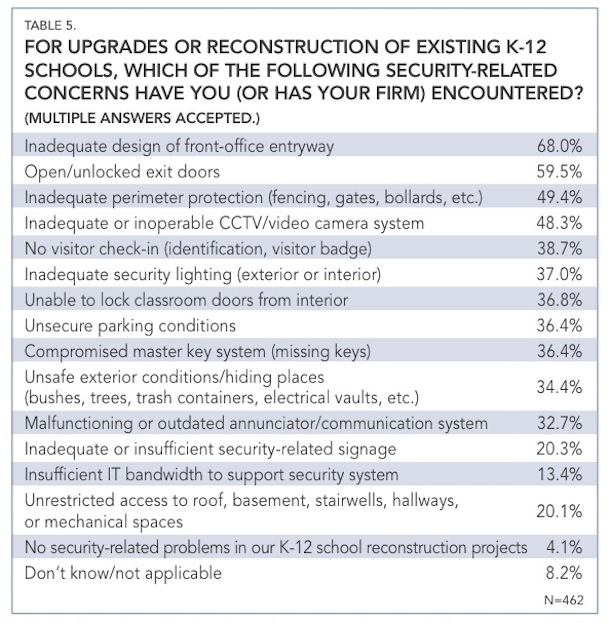

Judging by the responses in Table 5, it would seem impossible to find an existing school, no matter how new, that didn’t have some security deficiencies. And remediating older schools for security purposes is no picnic. “Design is so much more difficult (as in strategic) when retrofitting a quarter-century-old (or even older) facility, as most educational facilities are,” said Connecticut architect and Certified Architectural Historian James Gibbs, AIA, NCARB.

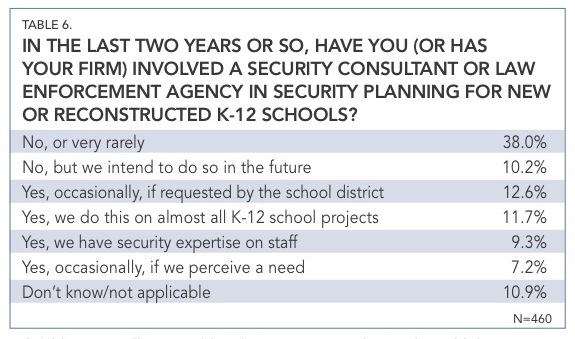

Whether certain technical experts should be included in planning security upgrades is another consideration. Looking at Table 6, James E. LaPosta, Jr., FAIA, LEED AP, Principal/Chief Architectural Officer with JCJ Architecture, said, “I would have expected a higher percentage of engagement with law enforcement or security.” Tech consultants also seem frustrated when school districts dismiss their expertise. “The trouble we find as integrators is finding school districts that will take the responsibility to train and understand the layers of security and how to implement those layers for an effective security solution,” said John Laney, a systems integrator with North Texas Communications.

School officials—administrators, principals, and board members—were deemed the power brokers when it came to decisions about improvements to K-12 security systems, according to a solid majority (62.0%) of respondents. The message for AEC firms: Work with officials in the school districts you serve to educate them on the role of security in design, construction, and master planning of their facilities.

School officials—administrators, principals, and board members—were deemed the power brokers when it came to decisions about improvements to K-12 security systems, according to a solid majority (62.0%) of respondents. The message for AEC firms: Work with officials in the school districts you serve to educate them on the role of security in design, construction, and master planning of their facilities.

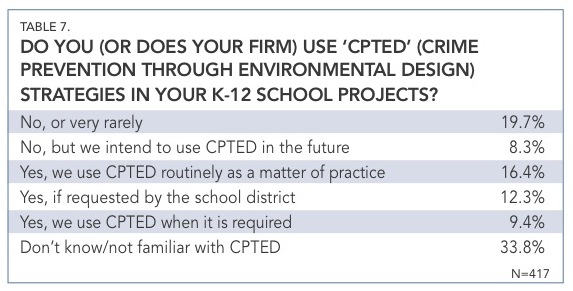

Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) drew support from many respondents (Table 7), including Doug Lau, AIA, LEED AP, with Brian R. Bloom–Architect. “We always seek ways to make the architecture address environmental needs, and using CPTED principles makes sense for designing new education facilities,” he said. “We use architectural passive solutions to address security, then use electronic systems as an additional layer of risk management.”

LITTLE RED SCHOOLHOUSE—OR THE NEXT FORT KNOX?

One ongoing concern has to do with the image of the school in our culture. There’s a strong aversion, particularly among architects, to making school buildings look hardened. “Unless we build schools like fortresses or windowless prisons (instead of friendly community places of learning and interaction), and spend millions on security and security staff, no amount of reasonable security will stop [such incidents] from happening,” said Daniel E. Michal, NCARB, Senior Project Architect, Hatch Mott MacDonald.

Schools don’t have to look like fortresses to be more secure, said Alan Brockbank, CPP, CSS, President, B-Secure Consulting. “Most schools can benefit from developing and enforcing security-related procedures, from security awareness training for staff, faculty, administrators, bus drivers, students, parents, and community members, and from assessing their current systems to ensure they are working properly,” he said.

Not surprisingly, money problems—no funds allocated, systems too expensive—are the main reasons school officials give for not upgrading their facilities’ security systems, according to AEC professionals. At the same time, respondents report only a small percentage of their clients (3.6%) aren’t worried about security threats, while nearly one-fourth (22.7%) said their K-12 clients are happy with whatever security systems they have.

Not surprisingly, money problems—no funds allocated, systems too expensive—are the main reasons school officials give for not upgrading their facilities’ security systems, according to AEC professionals. At the same time, respondents report only a small percentage of their clients (3.6%) aren’t worried about security threats, while nearly one-fourth (22.7%) said their K-12 clients are happy with whatever security systems they have.

Balancing the demand for higher levels of security with the aspiration for high-quality design takes seasoned judgment, said John W. Bollinger, PE, Mechanical Engineer/Project Manager, Boulder Valley (Colo.) SD. “It’s a fine line to walk between having a school be a welcoming place and having it look like a prison,” he said. “We need to be conscious of the security needs while still making the building function as a community resource.”

TAKING THE BIG-PICTURE VIEW?

Schools need to take a comprehensive approach to security, said Charles A. Berns, President, R. L. Sohol General Contractors, Inc. School perimeters must be protected. Academic areas should be segregated from community activity areas. Perimeter doors must be operable and equipped with electrified sockets for lockdown. Intercoms and two-way radios have to be fully operational. Proper security lighting must be in place. Entryways must be designed for positive visitor control.

Most important, said Berns, “Security must be applied in a consistent and uniform manner across the school district.”

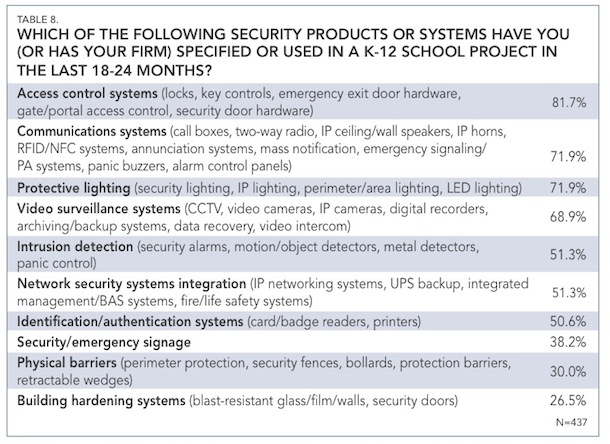

Looking at the panoply of security options in Table 8, Dale Junttila, President of Finnwood, a facilities project management firm in Eden Prairie, Minn., said, “Even with all these security measures in full working order, an individual or group might still breach the school.” His conclusion: “We can certainly make school facilities more secure, but we can’t make them perfect.”

That ol’ bugaboo of school security—poor entryway design—was reported by more than two-thirds of respondents (68.0%), followed closely by open-exit-door syndrome (59.5%). The wide array of security shortcomings reported by survey respondents may be the most important indication of the significant risk at which existing schools are operating.

That ol’ bugaboo of school security—poor entryway design—was reported by more than two-thirds of respondents (68.0%), followed closely by open-exit-door syndrome (59.5%). The wide array of security shortcomings reported by survey respondents may be the most important indication of the significant risk at which existing schools are operating.

A fairly even split was evident between respondents who said they use a security consultant or law enforcement agency for school planning or have security expertise on staff (40.8%) and those who do not (38.0%), with another 10.2% saying they plan to do so in the future.

A fairly even split was evident between respondents who said they use a security consultant or law enforcement agency for school planning or have security expertise on staff (40.8%) and those who do not (38.0%), with another 10.2% saying they plan to do so in the future.

A majority of respondents (53.5%) either have no familiarity with CPTED (33.8%) or have used it only rarely (19.7%). On the positive side, a sizable contingent (38.1%) use CPTED in school projects, with another 8.3% saying they plan to do so in the future.

A majority of respondents (53.5%) either have no familiarity with CPTED (33.8%) or have used it only rarely (19.7%). On the positive side, a sizable contingent (38.1%) use CPTED in school projects, with another 8.3% saying they plan to do so in the future.

AEC firms are installing plenty of access control, communications, protective lighting, and video surveillance systems in K-12 schools, judging by the high level of response to specification or use of these components. Yet barely half have employed intrusion detection (51.3%) or identification systems (50.6%), which security consultants say should be important elements of any school security system. Even security/emergency signage seemed low (38.2%).

AEC firms are installing plenty of access control, communications, protective lighting, and video surveillance systems in K-12 schools, judging by the high level of response to specification or use of these components. Yet barely half have employed intrusion detection (51.3%) or identification systems (50.6%), which security consultants say should be important elements of any school security system. Even security/emergency signage seemed low (38.2%).

METHODOLOGY

The survey was conducted November 18–25, 2013, across a sample of 9,929 current subscribers to Building Design+Construction who are actively involved in the design and construction of K-12 schools and who specify security and life/safety products and systems. A $25 gift certificate was awarded as an incentive to the first 10 respondents to complete the survey. A total of 462 usable responses were recorded, resulting in a margin of error of 4.45% at the 95% confidence level. Respondents by profession: architects, 58.2%; engineers, 20.8%; construction professionals, 17.3%; others (including school officials, security consultants), 3.7%.

Related Stories

| Dec 15, 2012

SAIC makes ready to lay off 700

SAIC, McLean, Va. (2011 construction revenues: $185,390,000), said it plans to cut its workforce by 700 employees in order to remain competitive in the federal market.

| Jun 1, 2012

New BD+C University Course on Insulated Metal Panels available

By completing this course, you earn 1.0 HSW/SD AIA Learning Units.

| May 31, 2012

2011 Reconstruction Award Profile: Seegers Student Union at Muhlenberg College

Seegers Student Union at Muhlenberg College has been reconstructed to serve as the core of social life on campus.

| May 29, 2012

Reconstruction Awards Entry Information

Download a PDF of the Entry Information at the bottom of this page.

| May 24, 2012

2012 Reconstruction Awards Entry Form

Download a PDF of the Entry Form at the bottom of this page.

| May 9, 2012

Construction Defect Symposium will examine strategies for reducing litigation costs

July event in Key West will target decision makers in the insurance and construction industries.

| Oct 17, 2011

Clery Act report reveals community colleges lacking integrated mass notification systems

“Detailed Analysis of U.S. College and University Annual Clery Act Reports” study now available.

| Sep 14, 2011

Research shows large gap in safety focus

82% of public, private and 2-year specialized colleges and universities believe they are not very effective at managing safe and secure openings or identities.