The School of Engineering at the University of Melbourne in Australia recently announced plans to build a new campus, to open in the early 2020s, that would feature large-scale research and training facilities to test emerging technologies that address global social and environmental issues.

One of those technologies is prefabrication for construction, and the university has taken a vanguard role to push prefabrication’s market share within the country’s construction industry to 15% by 2025, from 5% currently. That increase would represent around 20,000 new jobs and 30 billion Australian dollars (US$21.1 billion) in growth.

“We are seeing huge demand in the building industry for new techniques that will allow for the development of faster and cheaper construction. The only way to reduce costs is to reduce the cost of manufacturing,” says Tuan Ngo, director of the Advanced Protective Technologies for Engineering Structures Group within the university’s Department of Infrastructure Engineering.

It's not always easy to pinpoint a movement's breakthrough moments. But an online article that Deloitte posted on February 26 makes the case for a high-rise project in Melbourne, completed in 2010, that deployed a construction technique where entire floors of the building were completed offsite and assembled onsite by snapping together the modules one on top of the other.

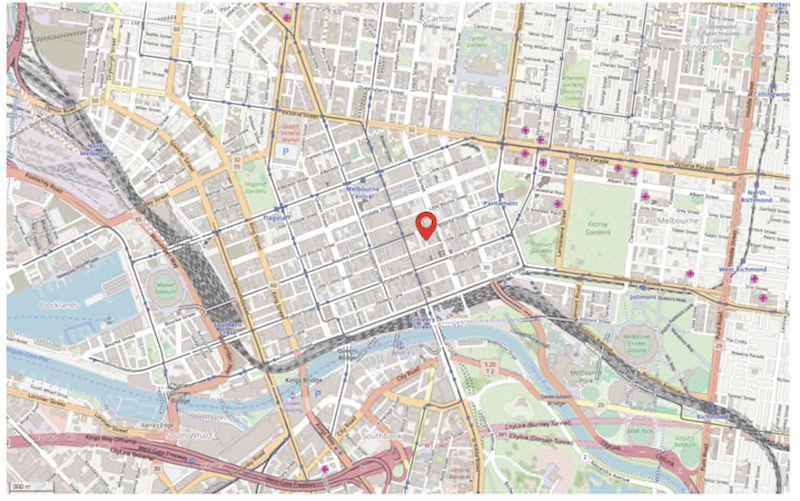

The location: Russell Place in Melbourne’s central business district. That real estate was problematic to build on because it sat over one of the district’s electrical substations. Weight restrictions limited the mass of any building constructed on the site, and ground vibration had to be minimized.

The land owner, a pre-eminent architect named Nonda Katsalidis, circumvented these roadblocks and restrictions by treating the construction process as a design-for-manufacture-and-assembly problem, rather than a building problem.

Russell Place, where the Little Hero building was assembled, sat over a primary electrical substation for Melbourne's central business district, which presented several construction limitations. Image: Deloitte Insights

Katsalidis’ twist on an already-established design-for-manufacturing technique was to “unitize” the building, so that each unit—in this case, each floor—was finished in a factory and then transported completed to the jobsite for quicker assembly, a la LEGO Duplo.

Executing this approach required making a digital model of the entire building, accurate to its light fittings, power sockets, washers, and door hinges. Deloitte’s authors called this BIM on steroids.

To pull this off, Katsalidis cofounded a technology company, Unitised Building in 2008, and partnered with a building firm Hickory Group to create the tooling required, and to develop and manipulate the models.

The Russell Place site was the first to host a building constructed with Unitised Building’s modular method. Completed in 2010, the building, called Little Hero, contains 63 one- and two-bedroom apartments and duplex penthouse residences, all of which sit atop seven retail shops, cafés, and restaurants. The unitized process not only complied with all of the site’s restrictions, but cut construction time by more than six months compared to a conventional approach: The eight-story building took only four weeks to erect, at a cost comparable to that of a conventional process.

Deloitte’s authors explain that what separated the unitized approach from conventional prefab modular design and construction at that time was that it was easier to customize, focused on mid- to high-rise construction, and allowed completed modules to be “snapped” together, in contrast to a kit of parts approach.

In addition, say the authors, unitization offered a new way to export BIM data. “It is possible for a firm to retain possession of the models and export only the instructions they generate, to guide the machines and workers in a remote contract manufacturing facility and the remote building site. The models are held domestically, where the engineering talent required to develop and maintain the IP in them is located.”

Deloitte’s authors note that unitization has since led to a larger discussion about different approaches to building as an activity. Rather than simply digitizing existing building practices … “we need to digitalize building by shifting the foundation of our operating model to a wholly different premise,” they wrote.

The unitized process sometimes requires improvisation, too. In 2017, Hickory Group was working on a site within Melbourne’s central business district where access was awkward. The crane that was needed to lift building units into place blocked a narrow laneway, making it difficult for local residents to access their properties.

To navigate the problem, the firm offered to build only at night. To prove this approach to skeptical a city council and residents, Hickory ran a trial build one night, which went unnoticed despite the firm warning nearby residents about it beforehand. With the council and residents convinced that installing building units at night would work, construction went ahead.

King 25, Australia's tallest timber building, was assembled using prefabricated engineered wood components. Image: Wonderful Engineering

Whatever success Unitised Building and other companies may have had, it remains to be seen whether prefab construction can get beyond the nascent stage in Australia.

Prefab, as a concept, got a boost when Australia’s tallest timber building, the 10-story 45-meter-tall (148-ft-tall) 25 King, an office and residential tower in Brisbane, opened earlier this month. Designed by the architectural firm Bates Smart, the building’s engineered-wood components were prefabricated offsite. The entire construction took 15 months to complete.

But supply and demand are still in question. One one hand, Strongbuild, which made prefab houses from an 8,000-sm (86,111-sf) factory in Sydney, last November lost a AUD$45 million contract and went into voluntary “administration,” Australia’s version of liquidation.

On the other hand, David Chandler, a former builder who is now adjunct professor in construction management at Western Sydney University, told the Australian Financial Review that the country could lose up to 200,000 construction jobs to offshore competition if it doesn’t set up a viable prefab construction industry within the next decade.

Related Stories

Building Technology | May 4, 2023

3D printing for construction advances in Germany

The largest 3D-printed building in Europe will have a much lower carbon footprint.

Mass Timber | May 3, 2023

Gensler-designed mid-rise will be Houston’s first mass timber commercial office building

A Houston project plans to achieve two firsts: the city’s first mass timber commercial office project, and the state of Texas’s first commercial office building targeting net zero energy operational carbon upon completion next year. Framework @ Block 10 is owned and managed by Hicks Ventures, a Houston-based development company.

AEC Tech | May 1, 2023

Utilizing computer vision, AI technology for visual jobsite tasks

Burns & McDonnell breaks down three ways computer vision can effectively assist workers on the job site, from project progress to safety measures.

Design Innovation Report | Apr 27, 2023

BD+C's 2023 Design Innovation Report

Building Design+Construction’s Design Innovation Report presents projects, spaces, and initiatives—and the AEC professionals behind them—that push the boundaries of building design. This year, we feature four novel projects and one building science innovation.

Building Technology | Apr 24, 2023

Let’s chat about AI: How design and construction firms are using ChatGPT

Tech-savvy AEC firms that already use artificial intelligence to enhance their work view the startling evolution of ChatGPT mostly in a positive light as a potential tool for sharing information and training employees and trade partners. However, the efficacy of ChatGPT is likely to rest on the construction industry’s aggregation of quality data that, until recently, has been underwhelming for getting the greatest bang from AI and machine learning.

Design Innovation Report | Apr 19, 2023

HDR uses artificial intelligence tools to help design a vital health clinic in India

Architects from HDR worked pro bono with iKure, a technology-centric healthcare provider, to build a healthcare clinic in rural India.

3D Printing | Apr 11, 2023

University of Michigan’s DART Laboratory unveils Shell Wall—a concrete wall that’s lightweight and freeform 3D printed

The University of Michigan’s DART Laboratory has unveiled a new product called Shell Wall—which the organization describes as the first lightweight, freeform 3D printed and structurally reinforced concrete wall. The innovative product leverages DART Laboratory’s research and development on the use of 3D-printing technology to build structures that require less concrete.

Contractors | Apr 10, 2023

What makes prefabrication work? Factors every construction project should consider

There are many factors requiring careful consideration when determining whether a project is a good fit for prefabrication. JE Dunn’s Brian Burkett breaks down the most important considerations.

Smart Buildings | Apr 7, 2023

Carnegie Mellon University's research on advanced building sensors provokes heated controversy

A research project to test next-generation building sensors at Carnegie Mellon University provoked intense debate over the privacy implications of widespread deployment of the devices in a new 90,000-sf building. The light-switch-size devices, capable of measuring 12 types of data including motion and sound, were mounted in more than 300 locations throughout the building.

Cladding and Facade Systems | Apr 5, 2023

Façade innovation: University of Stuttgart tests a ‘saturated building skin’ for lessening heat islands

HydroSKIN is a façade made with textiles that stores rainwater and uses it later to cool hot building exteriors. The façade innovation consists of an external, multilayered 3D textile that acts as a water collector and evaporator.