Just about every architect worth their measure develops a design process that works for them - it’s almost like a fingerprint, it’s that unique. In today’s episode, Andrew and I are going to talk about design, and we are going to do it in a manner that’s proper to the sort of design conversation that you might hear if you were sitting next to two architects at a bar. We've had a million of these sorts of conversations, and when I decided to actually start recording a podcast, this is exactly the sort of thing I had in mind.

I will admit that Andrew and I have to come up with these podcast topics months in advance and after we’ve had some time to sleep and do some other things, there are instances when the time comes to record a particular topic and neither one of us can remember what we were thinking (maybe because we came up with these topics while sitting at a bar?) For the last few weeks I have been ruminating on the idea of Big Designs / Small Details and I finally settled on the direction I want this conversation to take.

I had just changed from my last office of 11 and taken on a position in a firm of over 100 people and I was in the midst of changing just about every aspect of my design process as I moved from bespoke residential and smallish commercial projects to working on projects where master plan yield studies and 300k, 500k, even 1 million square foot buildings are not atypical … and the change of scales was a pretty big departure from the majority of past experiences.

The “white” paper design process on residential [ 4:01 mark]

One of the things that seem to be uniquely different from the residential design process from that of a commercial design process is the size of the initial concept idea. When I start a residential project, the first thing I do is sit down with the client and talk about their dreams and aspirations – exactly what do they want to accomplish with this project. It is also during this time when we talk about how they might want their project to look – could be as simple as “modern” or “traditional” but it is not that unusual to get into conversations about materials, light quality, who gets up first in the morning, how do they use their kitchen, do they entertain, and on and on – all of this even before we start considering the actual “house” part of the project.

This is an incredibly personal process – something that I’ve talked about dozens of times on this site – and when the actual design process starts, more times than not, the entire project grows out of a singular idea or concept and as this idea grows and expands, the entire project evolves into something that allows everything to work together in a homogeneous manner. I’ll give you a quick example and I’ll use a project that was covered extensively on this site – the Cabin project.

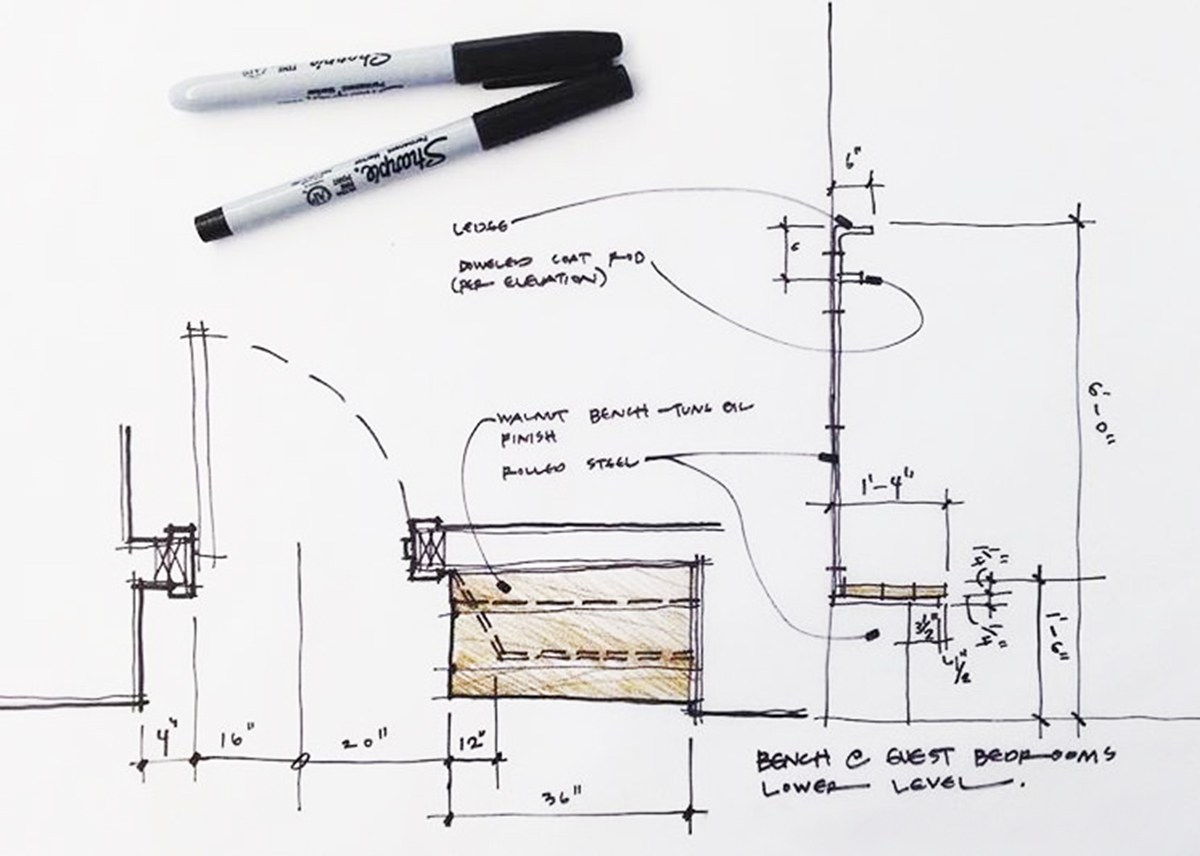

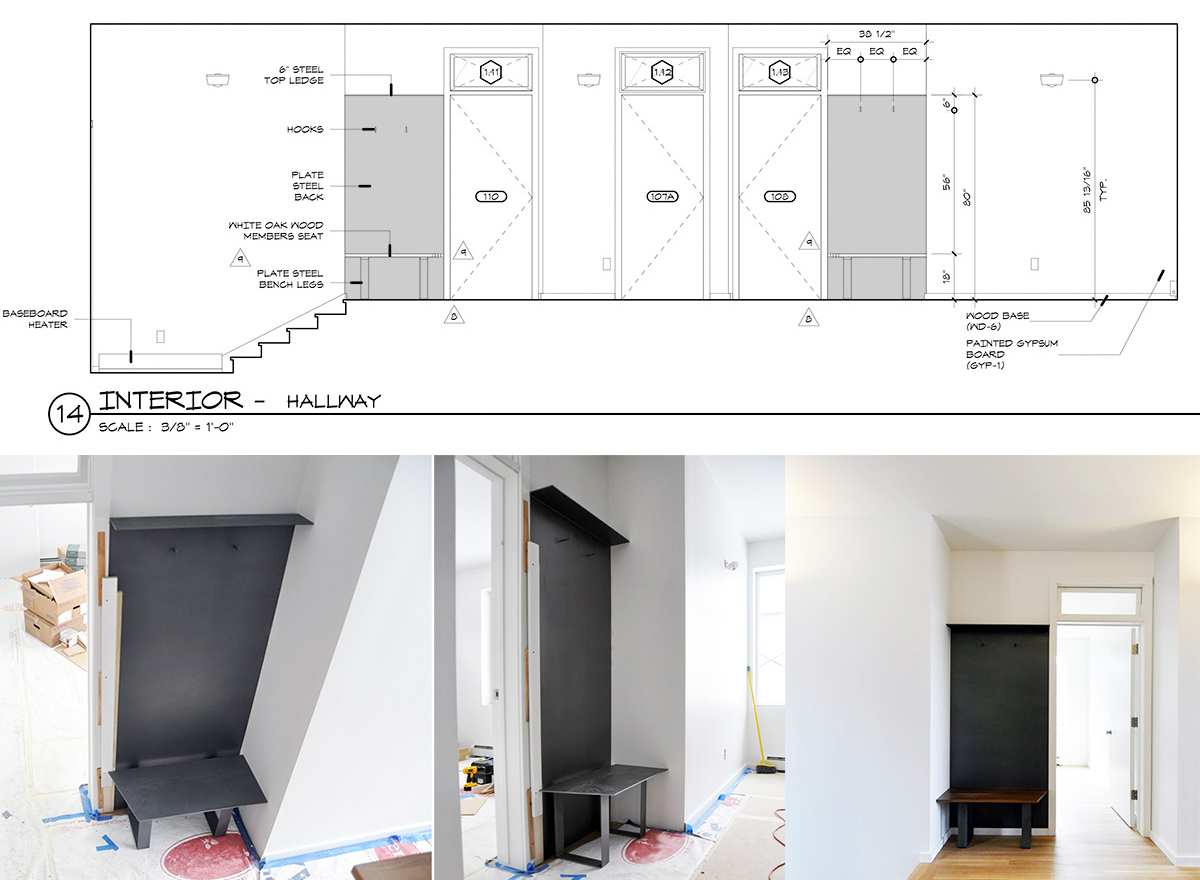

If you don’t know, this cabin project was done for a family that already had a family house on the adjacent lot and what we were tasked with doing, was to build a cabin that was for the benefit and use of the guests that come and visit during the summer months. The sketch above was the original idea of a bench outside of each guest bedroom and it embodied an idea of service and hospitality between host and guest.

Since this is a lake cabin, the owners have a revolving door of house guests – and sometimes there is more than one family visiting at the same time. What we wanted to do was design an entry point to each bedroom that would welcome these visitors to the cabin and give them the things they would need during their stay. These benches, sitting outside of each bedroom, have a role to play. The benches provide a spot for the host to place extra towels and blankets – there are hooks where jackets specific to the occupants can be hung, there is a shelf where books, small games, even spare toiletries can be placed.

I wrote a post about this particular bench before (Cabin Detail – Steel and Walnut Bench) and there you can see more construction drawings, fabrications photos but I think this singular item is a good representation of how a single idea can be used to develop architectural concepts that could be used to design an entire project.

But where does the commercial design process fit into this?

White paper design process on the Commercial design process

• Big gestures

• Data-driven design – there is a lot of internal intelligence baked in because the clients already know a very high level of information about how this process works.

• Small details are rarely a part of the process during the initial conceptual and schematic design process and so far, those small details are not driving the concepts.

I thought I would show some images from a project I have been working on for the last two weeks – interesting to me on several levels, not eh least of which is that this project was developed in large part in a vacuum as I worked in isolation with only the occasional peer review every few days.

This is a 285,000 square-foot office building that we are developing as part of an RFP (Request for Proposal) submittal. There are 7 people working on this particular project (along with a bunch of other projects) and we were all asked to develop our own schemes. After 2 days, we got together (digitally) did an internal present and review process, the result of which was we eliminated two schemes, and continued our work so that we could present the remaining 5 to our clients. The images I’ve shown above (not realizing I would use them for this post) represent about 2 days worth of my efforts. The top row was after day 1 – where I was simply trying to develop my concept for the building The bottom row represents the end of day two as the building starts to become “more real”, meaning I am considering the realities of this building and I’m working through structural spacing, building core layout, structured parking, etc.

At this point in the process, I am making all the assumptions on how this building will work, what the experience for the users will be, what the material palette will consist of … everything. Other than knowing the desired size of the building and location of the site, there has been no additional client input. We presented the 5 schemes to the clients and from those entries, they chose 3 to continue to develop so that they could be included in the proposal for services. Happily, mine was one of the ones selected for continuation.

Advance forward a few days and we are now back together as a team and critiquing the final iterations of the remaining three concepts. The entire project is considered, building core is resolved, materiality in place … this is for lack of a better way to describe it, a viable building.

And it was all put together in just a few days.

Everything you see in these images was done by me, sitting at a folding table in my bedroom as I work from home. The model was done in SketchUp and Enscape was used to create these renderings. The thing that made me want to show you project, other than it represents something that I actually did in the last two weeks, was that it also embodies the idea that workflow and creative process is very different between commercial and residential work. Our clients expect us to know all the moving parts associated with designing an office building of this size and complexity. In a sense, this is easy work and the creative process is much less encumbered by the aesthetic opinions of the client. For them, it needs to be the right size, functionally perform, fall within certain cost parameters, and demonstrate any opportunities we can rationally justify along the way.

It is very liberating from a design standpoint.

This building did not sprout forth from the germination of a single idea. It is rooted in a hundred more practical matters and if we did take the time to separate out creative problem-solving from aesthetic problem solving, you could quickly get to an understanding of the “Big Idea.”

This week’s hypothetical question has us leaving planet earth for destinations afar. [44:12 mark]

"Would you sign up to be a colonist on another planet if it meant you would never be able to return to earth? Most colonists tend to be able to drag their families along with them so that could be a consideration – both good and bad. You might want to go but your significant other or kids might not want to leave …"

There is only one answer to this question – and we all know it – but just like any good hypothetical question, the fun takes place when you start to try and wreck the other person’s answer. What if you only have a 50/50 chance of reaching your destination? What if your family can’t come along with you? Do you even have the skills or abilities to be useful to colonize a planet?

So what is the summation to this topic? Well, as a conversation had over drinks in some hotel lobby bar, there is no summation as this topic is pretty large and could go on enjoyably for a few more rounds. But since we aren’t actually sitting in a lobby bar, and I am writing this up beer-free on a Sunday afternoon, here you go:

The process and creative flow for large and small projects stem from the expectation of what end product will be delivered to your client. This process is also influenced by the knowledge that your client has of both this process and the end product. The expectation of my commercial clients has more to do with the practical realities of creating a building … rarely does it appear that there are dreams involved in this sort of work, whereas residential work is far more personal and the creative process is much about exploration and discovery with your client and less about the “I don’t want my roof to leak” sort of conversations. They are both incredibly rewarding and interesting but in completely different ways.

Cheers and stay safe,

Life of an Architect would like to thank Sierra Pacific Windows for their gracious support of this episode as well as our media partners, Building Design+Construction. If you would like to learn more about Sierra Pacific, their products, or to schedule a lunch and learn, please visit their website for additional information.