What is the meaning of sustainability in architecture? What are the guiding principles of a design response that is at once ecologically holistic, socially just, and zero-carbon? Miller Hull has always believed that buildings are capable of facilitating great change. Prompting humans to reexamine our relationship to the environment, architecture creates the opportunity for us to physically experience ideas of beauty, performance, and structure through the distinct lens of place.

While our practice has been centered on sustainability since our very first project, it becomes increasingly evident as we evolve that the most transformational buildings are the ones that are living and in tune with their natural systems and climatic conditions. At present, our firm is responsible for six buildings that are Living Building Challenge-certified, an official certification achieved through the stringent adherence to a variety of rigorous performance standards.

Representing the pinnacle of sustainable design, these buildings are more than a response to a challenge—they are indicative of a practice that celebrates the possibilities inherent to the built environment, and cherishes the wellbeing of people, planet, and place.

Our Process

Each Miller Hull project is born out of a conceptual investigation. Our design process involves early project musings where we investigate potential concepts born out of critical certainties in the program and site, as well as not so obvious certainties that interest us—the project “truths.” These truths can lead to elegant, clear, and meaningful concepts. Conditions of ecology, resilience, and social equity are, of course, honored and explicit in these concepts.

Working in a studio environment—an extension of the academic model—project teams take the theoretical to the practical in highly interactive and collaborative working sessions. Diagrams, hand-drawn sketches, physical models (many!), and computer-generated visualizations are dynamic tools that are engaged in our process. Climate data and socio/cultural research form not only the foundations for our conceptual proposals, but are employed throughout all phases of the design work. This research provides a solid theoretical footing and a means to expand the traditional formal constructs often seen in contemporary architecture.

In these explorations our design process is fluid and not always linear—described as a “comings and goings” by Professor Brian Carter in writing about the work of Miller Hull. From these investigations, ideas generated are tested and evaluated to ensure the appropriateness of proposed solutions. As featured in this book, this process has led to an exciting series of revelations about the potential of environmental architecture—an architecture that is simultaneously pragmatic and unique in both space and form that produces genuine inventions.

Two projects, one early and one more recent, demonstrate the consistency that this design approach has yielded throughout the years. Both projects are shown in early sketch form to illustrate the process over the finished form.

1. The Hansen Residence

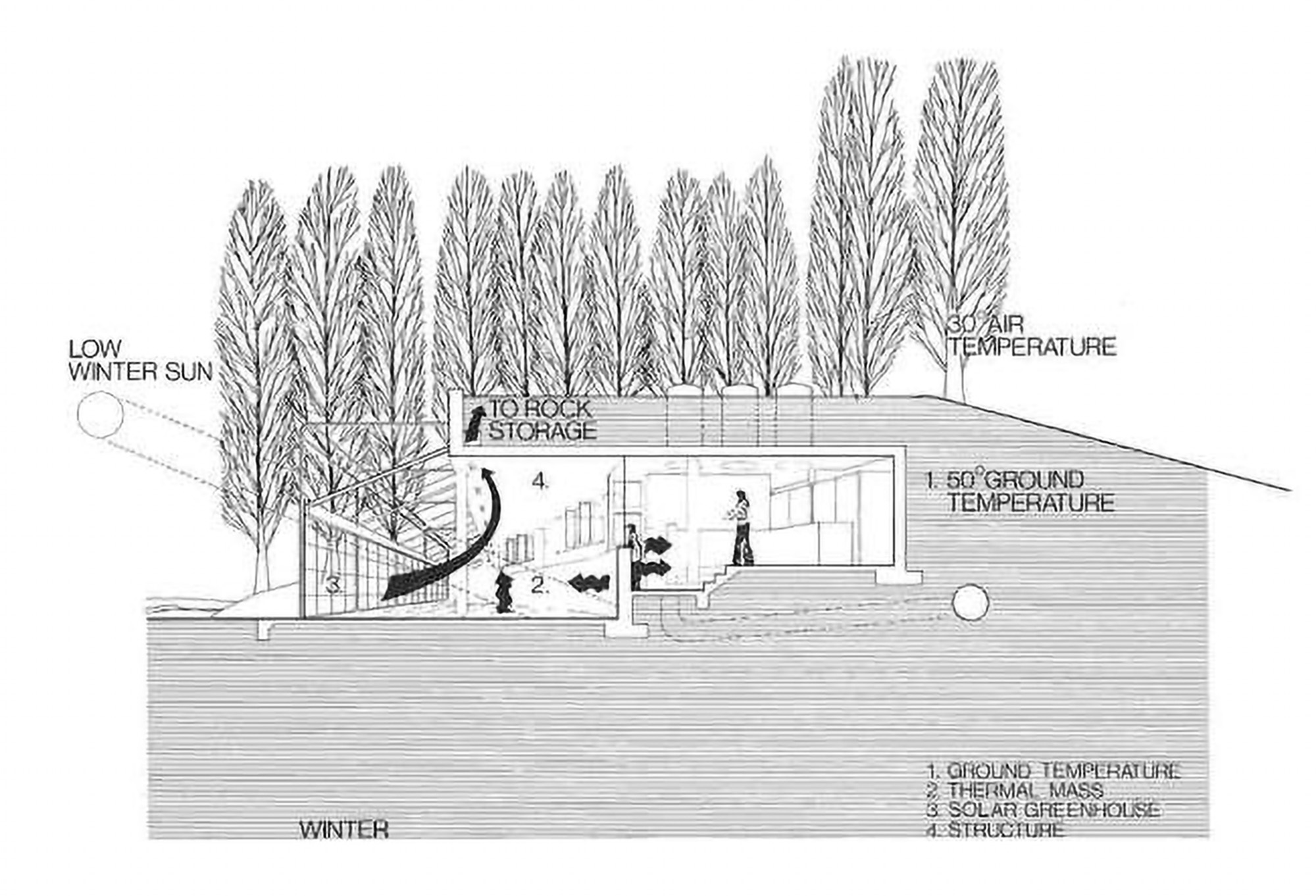

Located in rural Washington State, this projects speaks to how building on the inherent qualities of a site, combined with local climate conditions can lead to a powerful solution. The totally passive solar project utilizes a ‘kit-of-parts’ approach with movable garage doors turning the house into a heat-capturing solar greenhouse in Winter, and a shaded outdoor porch in Summer. The earth-sheltered concept takes advantage of the land’s stable temperature of 55 degrees, wrapping the residence in a blanket of benign microclimate, thereby greatly reducing winter heating and summer cooling loads. This project won national design awards and was highly published, launching the firm as significant contributors in the emerging passive solar movement of the early seventies.

2. University of Michigan, Art & Architecture Building

The addition to the Art and Architecture Building at the University of Michigan is a more recent project that also employs a passive systems approach. Connected to the existing 1970’s two-story building, the proposed south-facing building façade is augmented with movable shading devices that optimize or minimize solar gain. Sliding doors connect ‘crit galleries’ to the outdoors during the spring and fall fair-weather days. This façade was designed to operate as a robust and dynamic system, responsive to the varying and often extreme climate conditions.

The addition serves as a new front door for the home of the architecture and planning departments, viewed as a signboard for sustainability, an expressed desire of the Dean and faculty. These two projects represent important steppingstones as Miller Hull explored and ultimately refined its environmental architecture, leading to our work with Living Buildings—as we like to say our “Living Practice.”

3. Downtown Seattle

A Living Practice is one that is evolutionary and at the same time revolutionary. So, looking to the future, Miller Hull strives to increase its impact on the built environment in leading by example with its design work and by engaging in greater advocacy in the political arena. As an example, the firm proposed a new green urban model for downtown Seattle: “The Right Way—Taking back Seattle’s Right of Ways,” a reimagining of public space creating tree-lined pedestrian corridors replacing many of the automobile-first streets and their sidewalks.

Our work’s goal is to be responsibly bold in vision and project execution. The Living Buildings we create are made possible by the Living Practice we nurture, as we aim to influence, advance, and transform the discipline of architecture by integrating high performance building with high art. This goal is possible, and our new book Challenge and Change presents a roadmap. The “challenge” is facing the gravity of climate-change head on with vigor. “Change” is made achievable by converting imagination into action and action into an executed reality; this creates architecture that is beautiful, net positive, highly resilient, and available to all.

More from Author

Miller Hull | Sep 6, 2024

How to promote wellness through interior design

We spend most of our lives inside, and the spaces we inhabit have the potential to greatly impact our health depending on the kinds of design decisions made.