What is a PTAC unit?

If packaged terminal air conditioning (PTAC) units were a federally regulated drug, each equipment sale would be required to include a list of side effects and cautionary notes. Unfortunately, the opposite is true—each PTAC buyer is instead provided with a catalog of unproven expectations. These PTAC performance myths, enduring for decades, have contributed to an outsized number of moisture and mold problems.

Over the past 30 years, building experts at Liberty Building Forensics Group (LBFG) have investigated hundreds of hotel moisture problems (involving thousands of guest rooms) and in the process, have observed three repetitive assumptions that appear to be completely ignored by the hospitality industry:

1. PTAC units cannot effectively ventilate interior spaces.

2. PTAC units cannot effectively pressurize hotel guest rooms.

3. PTAC units are often ineffective in dehumidifying hotel guest rooms, especially when outside conditions are hot and humid.

Even though there is strong evidence that PTAC units cannot consistently provide these stated (or implied) features, the astonishing truth is that the entire hotel industry (including owners, operators, developers, contractors, and designers) seems to believe that they can. In response to concerns by designers and hotel operators, PTAC manufacturers have added additional outdoor air fans and coils to try to improve the outdoor air supply concerns. In our experience, the impact of these adaptations has not been fully understood or vetted.

Example of a mold problem caused by PTAC-related issues in a relatively dry climate after vinyl wall covering was removed from a demising wall between guestrooms.

Example of a mold problem caused by PTAC-related issues in a relatively dry climate after vinyl wall covering was removed from a demising wall between guestrooms.

Sign up for our Free September 13 webinar on “3 Myths of PTAC Units”.

For decades, the hotel industry has used PTAC or packaged terminal heat pump (PTHP) units (collectively referred to here as PTAC units). Dating back to at least the late 1980s, moisture, mold, and odor problems related to PTAC units have plagued the industry, especially in warm, humid climates. While these units have not caused problems every time they were used, nor have these problems occurred equally in every climate, the issues have been relatively pervasive and, in some cases, catastrophic.

Inconsistent failure patterns have helped perpetuate the unfounded belief that PTAC units can effectively achieve what the manufacturer’s literature implies. Acceptance of this myth has resulted in design decisions that are counter to both good building practices, emerging green building codes, and increasingly stringent energy efficiency building codes.

Overview

Low initial cost and simplicity, two of the most appealing features of PTAC units, are the primary reasons they are the standard choice for many hotels and dormitory-type facilities. Typically, designers or contractors install these simple systems and then let the occupants or building owners decide the room temperature. If good temperature control and low initial costs were the only expectations for PTAC units, they would be the perfect option for many facilities. In fact, when everything works perfectly, PTAC units provide a good solution to an important business challenge for the hospitality industry―how to achieve good guest room temperature control for the lowest initial cost.

PTAC units are actually expected to accomplish important additional functions, which we’ll address below. The inability of PTAC units to meet these additional expectations has been the cause of many moisture and mold problems over the past several decades. While the problems are typically more severe in warm, humid climates, we’ve also seen them occur in temperate climates (Figure 1).

Since there’s an absence of specific PTAC performance data (despite large numbers of hotels with PTAC units that should be provided with the required information), designers, contractors, developers, and owners usually rely on unproven statements in the manufacturer’s literature. Often, the resulting problems end up in court, where any lessons learned are not widely distributed to the hospitality design and construction communities.

PTAC Myth #1 – The Myth of Adequate Outside Air (OA) Ventilation

Myth: PTAC units can provide code-required ventilation air to the occupied space.

Reality: PTAC units do not provide code-required ventilation (even though this myth is an almost universal belief within the hotel design and construction industries) for the following reasons:

● The pressure drop through the vent door/air filter is higher than the pressure drop through the evaporator coil/filter, especially as the vent door filter becomes dirty.

● The guest controls the PTAC fan and can choose any speed available, including OFF, which eliminates any possibility of fan-assisted ventilation air. If the design relies on the equipment to meet the ventilation code, then the occupant or guest cannot be allowed to change fan speeds or turn the unit off.

● There is not a way to accurately measure the outdoor air flow to verify compliance with codes.

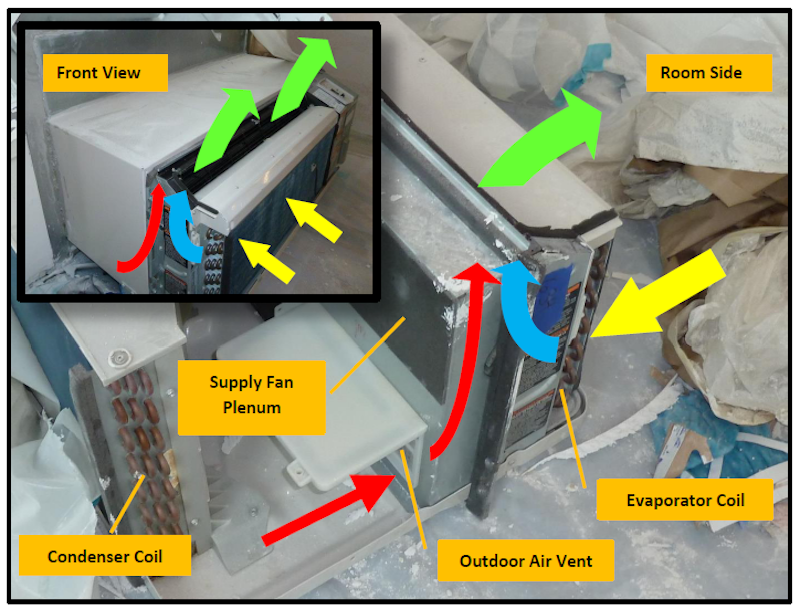

The photographs in Figure 2 were taken during the investigation of moisture problems in a location where only the summer months are humid (northern West Virginia), and where the PTAC unit design was intended to provide code-required ventilation to the guest room. Note that the vent damper is open, and the path for ventilation (outdoor) air is past the outdoor (condenser) coil and through a washable filter. The ventilation air in many PTAC units does not pass through the cooling coil before being mixed with the return air. This can result in increased room humidity.

PTAC Myth #2―The Myth of Positive Building Pressurization

Myth: PTAC units can positively pressurize guest rooms.

Reality: PTAC units cannot pressurize building spaces, because in order to do so, the following would have to occur:

● The ventilation air pulled through the vent door would have to exceed the toilet exhaust and room air leakage volumes. This does not happen.

● The PTAC fan would have to be able to provide pressurization regardless of wind effects. Wind effects can overpower PTAC fans, however, and will actually draw air out through the vent door on the leeward (negative pressure) side of the building.

● The PTAC fan must operate at all times when the room is occupied (for ventilation) or when the toilet exhaust is operating (for pressurization), regardless of what the guest desires. Guest control of the PTAC can result in intermittent fan operation, however, which will cause periods without positive pressurization even if the above two conditions did occur.

PTAC Myth #3―The Myth of Good Dehumidification

Myth: PTAC units provide good dehumidification under the majority of circumstances and in virtually all climates if operated correctly.

Reality: PTAC units do not provide good dehumidification. In order to do so, the PTAC unit would need to meet the following conditions:

● Be properly sized for full load and partial load conditions so that there is adequate cooling to remove the latent load during all operating conditions. Instead, PTAC units are often oversized because of conservative load analyses and the industry belief that temperature control is more important than anything else for guest comfort. This oversizing often results in insufficient run times to achieve passive dehumidification based upon temperature control only.

● Be able to condition the intended outside ventilation air through the vent door during occupied modes. Air pathways to the occupied space in most PTAC models do not encourage outside air to pass through the indoor coil (if any air is even introduced) before being supplied to the room. (See Figure 2.)

● Be able to control guest temperature expectations while still accomplishing the first two requirements. Guest control for comfort often prevents dehumidification because the thermostats controlling PTACs do not have the ability to control humidity. When a guest or hotel operator turns off the PTAC unit, then no dehumidification occurs.

Conclusions

Not all PTAC hotels have moisture and mold problems, but many that do experience significant and even catastrophic problems. These problems are predictable and avoidable, but prevention means understanding what these units can and cannot do.

Many industry parties (designers, manufacturers, and developers) have a strong incentive to continue believing the myths above while failing to seek proof of PTAC performance. If PTAC units actually performed all the functions that were claimed (or implied), they would be one of the least expensive and least complicated HVAC solution ever invented. The alternatives to using PTAC units are more expensive and require more installation space, more equipment, and additional maintenance expense - but they work!

The solution to the limitations of PTAC units is to use a fully ducted and conditioned makeup air system in combination with the PTAC units, rather than expecting door undercuts to provide transfer air from corridors or adjacent spaces.

Certain measures can be taken to reduce the likelihood of moisture and mold problems in PTAC hotels where installing a ducted makeup air system is not practical (e.g., existing facilities) or where the owner is not willing to accept the additional costs of a makeup air unit. These measures include: 1) reducing toilet exhaust rates to the lowest allowed by code to reduce negative building pressures; 2) replacing oversized PTAC units with smaller units to reduce overcooling; and 3) eliminating vinyl wall coverings on all interior wall surfaces.

Notwithstanding the limitations and risks of using PTAC units, those that have traditionally relied on them will probably continue to do so. Quite simply, for many people, the lower initial cost of using PTAC units without ducted fresh air systems offsets the increased risks of potential moisture, mold, and ventilation problems. The single factor that may cause an HVAC marketplace transformation is increasingly stringent green building standards and energy codes that may no longer allow uncontrolled and unconditioned air flows through open holes (i.e., open PTAC vents) in every guest room.

Click here to read a more comprehensive blog on this issue.

Download our free e-book on “The Single Most Important Factor

in Reducing the Risk of a Mold and Moisture Lawsuit in Your Next Project.”

About the Authors

Richard Scott-AIA, NCARB, LEED AP is a building expert at LBFG and J. David Odom is a retired LBFG building expert. Norm Nelson is a Senior Technologist at Jacobs Engineering.

Mr. Odom was a Senior Building Forensics Consultant with Liberty Building Forensics Group. He has managed some of the largest and most complex mold and moisture problems in the country, including the $60M construction defect claim at the Hilton Hawaiian Village in Honolulu and the $20M claim at the Martin County Courthouse. He has also managed over 500 projects for the Walt Disney Corporation dating back to 1982 that have included technical issues related to corrosion, moisture, and design & construction defect-related problems.

Mr. Scott, a Senior Forensic Architect at LBFG with more than 35 years’ architectural experience and an expert in building envelopes, has conducted more than 500 forensic investigations and has helped solve some of the most complicated mold and moisture failures in the world.

Mr. Nelson, a forensic mechanical engineer who investigates indoor air quality and moisture problems within buildings, specializes in energy efficiency retrofit of existing buildings, as well as commissioning and retro-commissioning of building mechanical systems. He designs mechanical systems for commercial, institutional, industrial, and residential projects.

LBFG has provided mold and moisture diagnoses and solutions for buildings to owners, contractors, and developers worldwide. The firm has project experience in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Europe. Contact us at g.dubose@libertybuilding.com or by phone at 407/467-5518.

More from Author

J. David Odom | Jan 4, 2018

The incredible predictability of moisture problems

Sign up for our free January 9 webinar on “The Predictability of Moisture Control & Building Air Tightness in High-Performance Buildings.