Those involved in the development of most sustainable green buildings typically use innovative products and implement new design and construction approaches. The intent of these new materials and procedures is to achieve a structure with reduced negative environmental impact, both during construction and throughout the building’s life.

These ambitions have now become a part of the International Green Construction Code (IgCC), but have their origin in early green rating systems and in early versions of codes like CalGreen. While the IgCC has been adopted in some jurisdictions as an alternative measurement for sustainable buildings, rating systems such as LEED® v4 have become more widely used. Both approaches, however, have had a similar influence on design, product selection, and construction means and methods.

One such example is the recent shift towards requiring low-volatile organic compound (VOC) products and materials in the new green code, representing one of the most significant changes in products that the construction industry has seen in some time. This shift is intended to improve the indoor building environment by eliminating the introduction of products and materials that can release specific VOCs into the building.

Unfortunately, case studies are proving that there are also significant issues associated with these product changes. One such case study highlighted below illustrates the challenges that the construction industry faces with regards to this issue.

Case Study: Educational Building

Recently a large educational building in a mid-Atlantic state was nearing the final stages of construction when mold growth and surface corrosion was discovered inside the ductwork system.

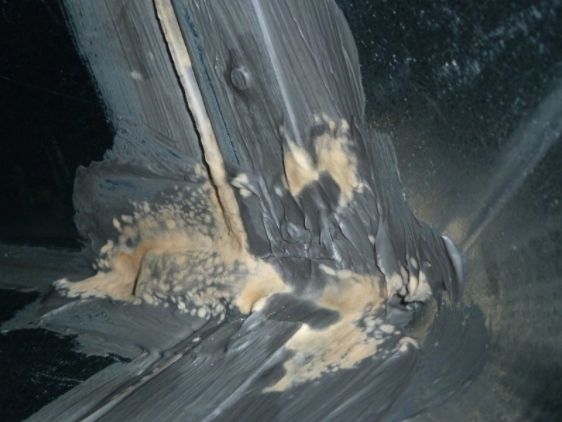

Figure 2: Note the mold growth on the water-based mastic.

Figure 2: Note the mold growth on the water-based mastic.

The building had been designed and was being constructed in an effort to achieve LEED® Silver. Based upon the architect’s established green criteria, the engineer had dutifully specified ductwork mastic that was water-based rather than solvent-based. The reasoning was that solvent-based mastic would definitely release certain undesirable VOCs into the building as it cured. Because water-based mastic dries rather than cures, it does not release significant levels of specific VOCs into the building during the drying process. This design objective was intended to be a part of an overall goal of reducing emissions from materials and controlling pollutants in the building, allowing compliance with codes like the IgCC and with USGBC rating systems like LEED® v4.

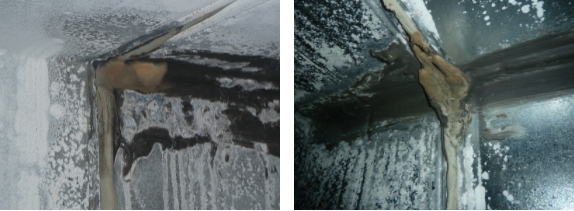

Figure 3: The mechanical contractor dutifully covered the ductwork’s open ends with plastic. Above, one cover was removed by the investigator to provide viewing inside the ductwork.

Figure 3: The mechanical contractor dutifully covered the ductwork’s open ends with plastic. Above, one cover was removed by the investigator to provide viewing inside the ductwork.

Next, the ductwork was being diligently covered with plastic, as was required by the specifications and as has also been considered good practice for some time in the construction industry. Protecting ductwork by covering it with plastic is also a requirement of the IgCC. In fact, the general contractor was being so diligent about this requirement that he would fine the mechanical contractor $500 for every opening found to be uncovered with plastic.

The project was progressing nicely, with the architect, engineer, and general and mechanical contractors implementing what they believed to be good practices and due diligence in the installation of the ductwork system: using low-VOC product mastic, covering the ductwork to keep it clean during construction, and applying mastic on both the inside and outside of the ductwork in order to produce low leakage ductwork rates. All of these are good practices intended to produce a high-performance building, and are consistent with what is contained in the various green codes, standards, and rating systems.

The problem is that these changes are not often well-understood by contractors - or even by designers, for that matter. The building industry has historically been conservative, relying on time-proven construction materials and methods. Over time, however, the industry has embraced a shift towards new materials and methods in order to meet market demands for price and speed in the delivery of buildings. Unfortunately, these new materials and methods have not always panned out, resulting in notable building failures with respect to moisture intrusion and subsequent mold growth. New green design goals and codes being introduced will add even more untried materials and methods to the construction process, increasing the risks of moisture problems.

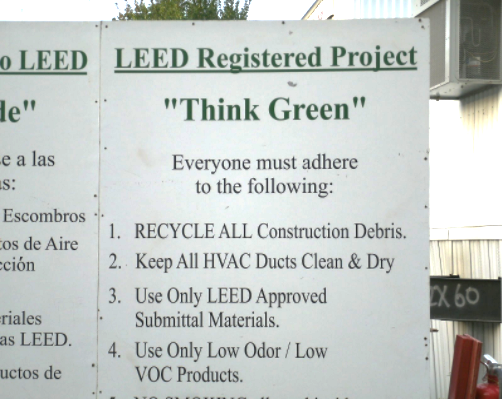

Figure 4: This sign was posted on the construction site as a reminder of the basic requirements of achieving the LEED® credits related to protecting the ducts and using low-VOC products.

Figure 4: This sign was posted on the construction site as a reminder of the basic requirements of achieving the LEED® credits related to protecting the ducts and using low-VOC products.

This new educational building was no exception. The ductwork being covered faithfully by the mechanical contractor, along with the application of a mastic that dries because it is water-based instead of curing as is the case with conventional solvent-based mastics, resulted in mold growth inside the ductwork that cost $1.5M in remediation before the building was even completed. The remediation efforts also jeopardized the construction schedule by requiring re-work by many of the subcontractors.

Figure 5: The ductwork required $1.5M in remediation of mold growth and surface corrosion prior to the opening of the building, which involved coordinating efforts amongst significant finished work.

Figure 5: The ductwork required $1.5M in remediation of mold growth and surface corrosion prior to the opening of the building, which involved coordinating efforts amongst significant finished work.

These decisions on their own were good and prudent, but together resulted in the unintended consequence of mold growth because the mastic had remained wet for several weeks inside the covered ductwork. In contrast, the traditional solvent-based mastic would still have cured even if the ductwork had been covered.

It is within this environment of intersecting decisions that any misunderstanding by contractors and designers will continue to be an area of high risk on projects. What risk? The risk of building failure due to the use and performance of products that are different from those with which we are familiar because they are now manufactured to meet new green objectives. It also becomes increasingly difficult for contractors and designers to mitigate against the risk of new products they know very little about interacting with other products or materials in the buildings. This is especially true when products are being used under varied conditions during construction.

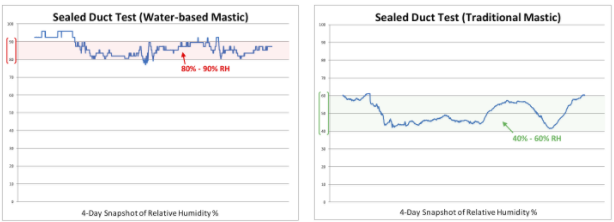

Figure 6: The graph on the left demonstrates how the water-based mastic kept the relative humidity (RH) inside the ductwork at levels that would grow mold. The graph on the right shows conditions in another identical ductwork section where the RH inside the ductwork would significantly reduce the opportunity for mold growth.

Figure 6: The graph on the left demonstrates how the water-based mastic kept the relative humidity (RH) inside the ductwork at levels that would grow mold. The graph on the right shows conditions in another identical ductwork section where the RH inside the ductwork would significantly reduce the opportunity for mold growth.

This being said, there are several strategies that can be employed by the contractor to mitigate against these risks. Some of these available tools are listed below:

- The contractor must clearly identify the new products being used in the building that are specific to achieving green objectives and which are unfamiliar to him. After this inventory of products is completed, a QC action plan should be established to target product implementation.

- The contractor needs to include the product manufacturer in the QC process. No other party knows more about the product than the manufacturer. The manufacturer should be made responsible for the following measures: meeting the specifications performance; monitoring the means, methods, and compatibility of the product and installation during construction; and verifying the product once it is installed.

- The contractor should recognize that means and methods for low-VOC products are different. For ductwork mastics, the ductwork needs to be covered with a product that is breathable, and plastic must be avoided. Products such as certain filtration media or even house-wrap materials like Tyvek® are options that will keep the ductwork from being impacted by construction dust while still allowing for the water-based mastic to dry.

- The designer or contractor should either hire a peer reviewer or recommend the hiring of one to the client. A peer review allows the design and construction team to insert expertise upstream in the design and construction process, which is especially important for moisture and mold control measures. Since the design and construction industry has one of the worst feedback systems from the field (with the only feedback typically coming through litigation), peer review experts allow the design and construction team to bridge the gap between building failures and successes.

Click here to read more about this issue.

Download our free e-book on “The Single Most Important Factor in Reducing the Risk of a Mold and Moisture Lawsuit in Your Next Project.”

About the Authors

George H. DuBose-CGC; Charles Allen, Jr., AIA; Donald B. Snell-PC, Cert. Mech. Contractor, CIEC; and Richard Scott-AIA, NCARB, LEED AP are all building experts at LBFG.

LBFG President George DuBose, with over 25 years’ experience in building failures and a focus on mold and moisture issues as well as HVAC and building envelope failures, is co-author of three manuals on IAQ and Mold Prevention, which have been used on over $4B in construction.

Chuck Allen, a Forensic Architect at LBFG with expertise in building envelopes and roofing and wall systems, has applied his expert architectural knowledge and cutting-edge technological skills on some of the largest and most complicated building failure projects in the world.

Don Snell, a Senior Forensic Engineer/Vice President at LBFG with over 25 years’ experience in all aspects of HVAC systems, has used diagnostic and remedial solutions to help some of the largest commercial builders in the world with catastrophic moisture and mold intrusion resulting from HVAC failure.

Rick Scott, a Senior Forensic Architect and building envelope expert at LBFG with more than 35 years’ architectural experience, has conducted more than 500 forensic investigations and has helped solve some of the most complicated mold and moisture failures in the world.

LBFG has provided mold and moisture diagnoses and solutions for buildings to owners, contractors, and developers worldwide. The firm has project experience in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Europe. Contact us at g.dubose@libertybuilding.com or by phone at 407/467-5518.