In preparation for hosting the Summer Olympics in Beijing in 2008, the Chinese government had a slew of mega redevelopment projects in the works. One of these, dating back to 2004, called for tearing down a decommissioned, 1950s-era weapons factory to make way for new vertical construction that the city desperately needed.

But since the late 1990s, that 148-acre area, located in the northeast corner of Beijing, had emerged slowly but steadily as an artists’ enclave. And the uproar that ensued over the plan to demolish the buildings on that site led to an unexpected shift toward preservation that, a decade later, continues to pay dividends for this city, and is still evolving.

At the time when the Chinese government was considering demolition, “there wasn’t a lot of reverence for historical buildings,” recalls Michael Grove, a principal with Sasaki, the Boston-based design firm that developed the master plan for this site.

The outcry against razing the buildings, coming from local artists and cultural groups, struck a chord. But any alternative plan still needed to produce a steady revenue stream, provide a destination for China’s arts community, and preserve the area’s character.

SevenStar Group, a government-led consortium that owns the area’s land and manages the factory workers’ pension fund, joined forces with Baron Guy Ullens—a Belgian businessman, philanthropist, and art collector, who opened the first privately owned contemporary arts center in China—to commission Sasaki to come up with a vision for converting this area into an arts district.

“Ullens was taking a huge risk” opening his gallery, says Dennis Pieprz, a Sasaki principal. But while Ullens’ initial lease was for only seven years, “he was thinking well beyond that.”

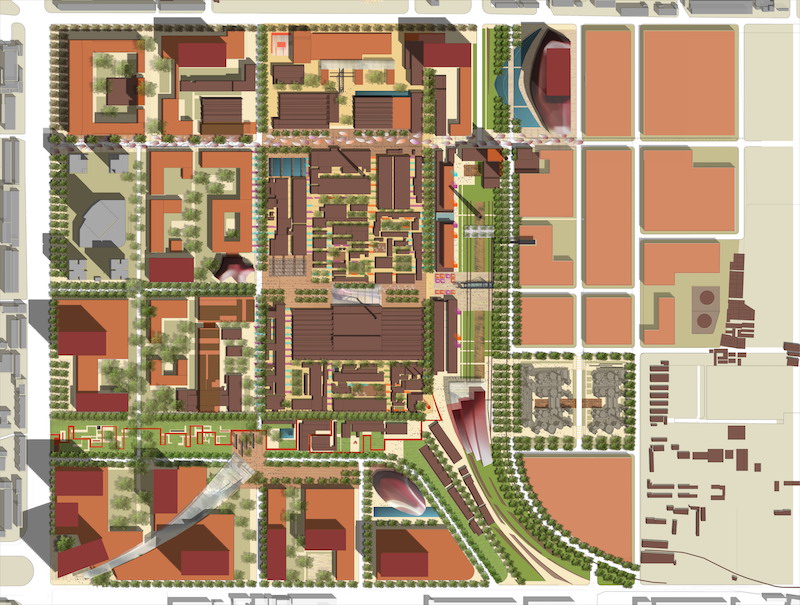

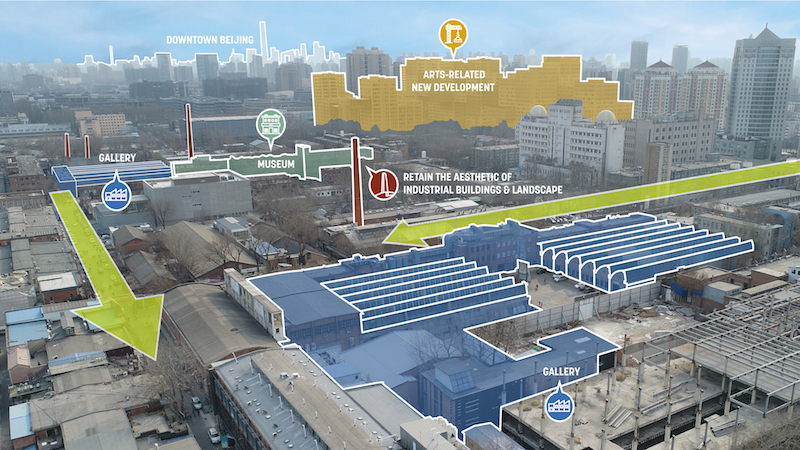

The 798 Arts Zone is wedged into 148 acres on the northeast corner of Beijing, where artists and creative tenants started gravitating to in the late 1990s. Image: Sasaki

Sasaki's master plan called for preserving many of the factory's buildings for exhibit and event space, and retaining the area's industrial landscape. The presumption was that this redevelopment would lead to new construction around the zone's periphery. Image: Sasaki

Sasaki was “captivated” by the factory district’s architecture and infrastructure, which resembled the Bauhaus style. The firm worked with Urbis Development (an entity owned by Ullens) to catalog the existing buildings and identify those that would remain, “which was a lot,” says Pieprz. The plan would also suggest the development and installation of key cultural structures.

The 798 Arts Zone was born, named after the number on the building that was the first into which artists had migrated. Sasaki’s master plan strengthened the district’s connections with nearby transit stations, and established the guidelines for the buildings’ adaptive reuse.

The district’s factory buildings became museums (including the Ullens Center for Contemporary Arts), galleries, restaurants, and shops. The outside space around the buildings became settings for sculptures, as well as fashion and culture events. By January 2008, more than 400 cultural organizations from several countries had settled into this arts zone, according to contemporaneous news reports.

In 2015, the Goethe Institut China opened a new center in Beijing's 798 Art Zone. The event space is used for cultural and artistic exchanges, strengthening cultural ties between China and Germany. Image: Sasaki

The 798 Arts Zone is China’s third most-popular attraction, along with the Great Wall and the Forbidden City, with more than 3 million visitors annually. It was the recent recipient of the 2018 Pierre L’Enfant International Planning Excellence Award. SevenStar still features the arts district on its website, says Grove.

“It’s not static, and has evolved over time. Our plan was meant to be flexible, to allow for creativity.” Both he and Pieprz, though, are surprised at how closely 798’s development has followed Sasaki’s plan, especially since “we didn’t have a lot of interaction with the landowner,” says Grove.

One of the striking art pieces on exhibit inside a converted factory at 798 Art Zone in Beijing. Image: Sasaki

New twists, possible additions

For the first time in several years, Grove returned to the district last February, and saw a number of new things:

•All of the plaza and public spaces that Sasaki inserted in its master plan “had been implemented”;

•There’s a ring of new development around the district, primarily low- and mid-rise office space for creative tenants such as ad agencies, media, fashion and software designers, and artists. “We wanted to avoid a sea of residential and office towers,” says Pieprz about what the master plan called for;

•One completely new building within the district is Audi’s Research & Development Center, which opened Feb. 1, 2013 inside the Audi China’s Building at 751-D Park. The 86,111-sf, six-story building has more than 300 employees and houses Audi’s labs and workshops for the Asia market. When it opened, this was Audi’s biggest overseas investment. “This building expands the district’s definition of art,” says Grove;

•An elevated walkway now meanders through the district. Grove says Sasaki’s master plan had called for a series of walkways, but the elevation surprised him. He speculates that this choice might relate to the success of New York City’s High Line.

798 Arts Zone still has a bohemian feel to it, and hosts myriad cultural events. The zone is the permanent home to the annual Beijing Queer Film Festival, despite China’s strict censorship laws. The international museum operator Pace has exhibit space in the district.

There’s always the fear, as with any popular venue, that 798 Arts Zone is becoming commercialized, gentrified, and high priced, especially when corporations like Audi, Uber, Volkswagon, and Canon have opened offices within its proximity.

But Grove and Pieprz agree that this kind of project, where incremental transformation occurs, is still rare. “Most projects are driven by scale, which is especially true in China,” says Pieprz.

The Sasaki execs also suggest that more changes could be in the offing. The firm’s master plan called for the eventual opening of a significant art school within the district. (Currently, there’s a small art school run by a Japanese tenant.) The plan also included a major performing arts center, and a railway that would run through a nearby park to the district. (The park, says Grove, has yet to be developed.)

Sasaki's master plan envisioned the inclusion of a “significant” art school. Image: Sasaki

When Grove was in the district last February, a design director for 751, one of the converted factory buildings, approached him about pursuing future development.

“Our master plan was a strategy to create value,” says Pieprz, to which Grove adds “it’s an example of a flexible framework versus a mega project.”

Related Stories

Adaptive Reuse | Jul 27, 2023

Number of U.S. adaptive reuse projects jumps to 122,000 from 77,000

The number of adaptive reuse projects in the pipeline grew to a record 122,000 in 2023 from 77,000 registered last year, according to RentCafe’s annual Adaptive Reuse Report. Of the 122,000 apartments currently undergoing conversion, 45,000 are the result of office repurposing, representing 37% of the total, followed by hotels (23% of future projects).

Urban Planning | Jul 26, 2023

America’s first 100% electric city shows the potential of government-industry alignment

Ithaca has turned heads with the start of its latest venture: Fully decarbonize and electrify the city by 2030.

Multifamily Housing | Jul 25, 2023

San Francisco seeks proposals for adaptive reuse of underutilized downtown office buildings

The City of San Francisco released a Request For Interest to identify office building conversions that city officials could help expedite with zoning changes, regulatory measures, and financial incentives.

Sustainability | Jul 13, 2023

Deep green retrofits: Updating old buildings to new sustainability standards

HOK’s David Weatherhead and Atenor’s Eoin Conroy discuss the challenges and opportunities of refurbishing old buildings to meet modern-day sustainability standards.

Multifamily Housing | Jul 11, 2023

Converting downtown office into multifamily residential: Let’s stop and think about this

Is the office-to-residential conversion really what’s best for our downtowns from a cultural, urban, economic perspective? Or is this silver bullet really a poison pill?

Adaptive Reuse | Jul 10, 2023

California updates building code for adaptive reuse of office, retail structures for housing

The California Building Standards Commission recently voted to make it easier to convert commercial properties to residential use. The commission adopted provisions of the International Existing Building Code (IEBC) that allow developers more flexibility for adaptive reuse of retail and office structures.

Adaptive Reuse | Jul 6, 2023

The responsibility of adapting historic university buildings

Shepley Bulfinch's David Whitehill, AIA, believes the adaptive reuse of historic university buildings is not a matter of sentimentality but of practicality, progress, and preservation.

Multifamily Housing | Jun 19, 2023

Adaptive reuse: 5 benefits of office-to-residential conversions

FitzGerald completed renovations on Millennium on LaSalle, a 14-story building in the heart of Chicago’s Loop. Originally built in 1902, the former office building now comprises 211 apartment units and marks LaSalle Street’s first complete office-to-residential conversion.

Multifamily Housing | May 23, 2023

One out of three office buildings in largest U.S. cities are suitable for residential conversion

Roughly one in three office buildings in the largest U.S. cities are well suited to be converted to multifamily residential properties, according to a study by global real estate firm Avison Young. Some 6,206 buildings across 10 U.S. cities present viable opportunities for conversion to residential use.

Multifamily Housing | May 16, 2023

Legislators aim to make office-to-housing conversions easier

Lawmakers around the country are looking for ways to spur conversions of office space to residential use.cSuch projects come with challenges such as inadequate plumbing, not enough exterior-facing windows, and footprints that don’t easily lend themselves to residential use. These conditions raise the cost for developers.