The terms “desire path” and “line of desire” bring with them a bit of a mystical feeling, as if they were something Indiana Jones would need to find a way to cross to get to the Ark of the Covenant or the Holy Grail that awaits on the other side. In reality, desire paths are not quite so fantastical.

Even if you have never heard the term desire path, odds are you’ve seen one at some point. If you’ve ever been walking around a college campus, public park, or downtown area, you have probably seen an informal dirt path that cuts a corner, or through a field, or even through a few small shrubs or bushes. This path isn’t paved and clearly wasn’t part of the original plan, but thanks to the desire of many to find the path of least resistance from point A to point B, it has emerged over the years from repeated use.

Desire paths don’t necessarily have to be so rustic, either. Lines of desire can also be represented by people using formalized roads or paths in ways they were not intended to be used, such as a service road that has become a main pedestrian thoroughfare.

In general, a desire path or line of desire represents any path that end users have determined to be the most efficient way to travel, regardless of its intended use.

“They reflect the natural tendency of where people want to move. These lines are predicated on there being barrier-free environments,” says Caitlyn Clauson, Principal, Chair at Large on Board of Directors, and Planner at Sasaki. “If areas are inaccessible, for example with a steep slope or a discontinuous sidewalk, individuals will find other routes. Desire lines are often informed by adjacent land uses, especially uses with active ground floor functions and high levels of transparency and shade that make spaces inviting and habitable.”

For many, especially planners and designers, a desire path is an unsightly reminder that a campus or downtown design plan was not as efficient and pedestrian-friendly as it could have, or perhaps should have, been. It proves just because something was designed to function a certain way, it doesn’t mean end users will necessarily follow suit.

There are two solutions to the scourge of the desire path: find a way to create a space so optimally designed desire paths won’t ever rear their ugly heads, or create a space so flexible that if a desire path does appear, it can be formalized and integrated into the design.

Sasaki’s CoMap helps spot ‘desire paths’ before they start

In order to prevent desire paths from taking shape, they need to be taken into consideration during a project’s earliest phases. “We did a feasibility study for UC San Diego in 2019 involving some developer land adjacent to campus and the campus architect was intrigued by my use of the term ‘line-of-desire’ in our initial meeting,” says Paul Schlapobersky, AIA, Associate Principal, Urban Designer, and Architect with Sasaki. “The entire study became about trying to ‘complete’ that line through a system of walkways and bridges connecting important nodes on the campus to this off-campus site and to newly-installed public transit beyond.”

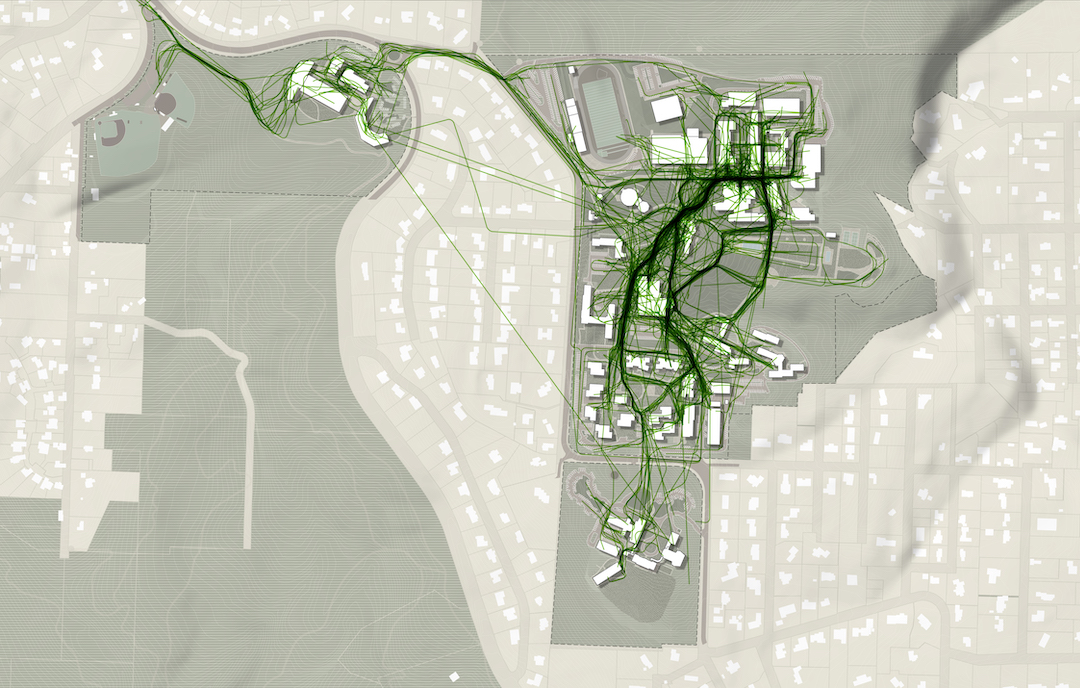

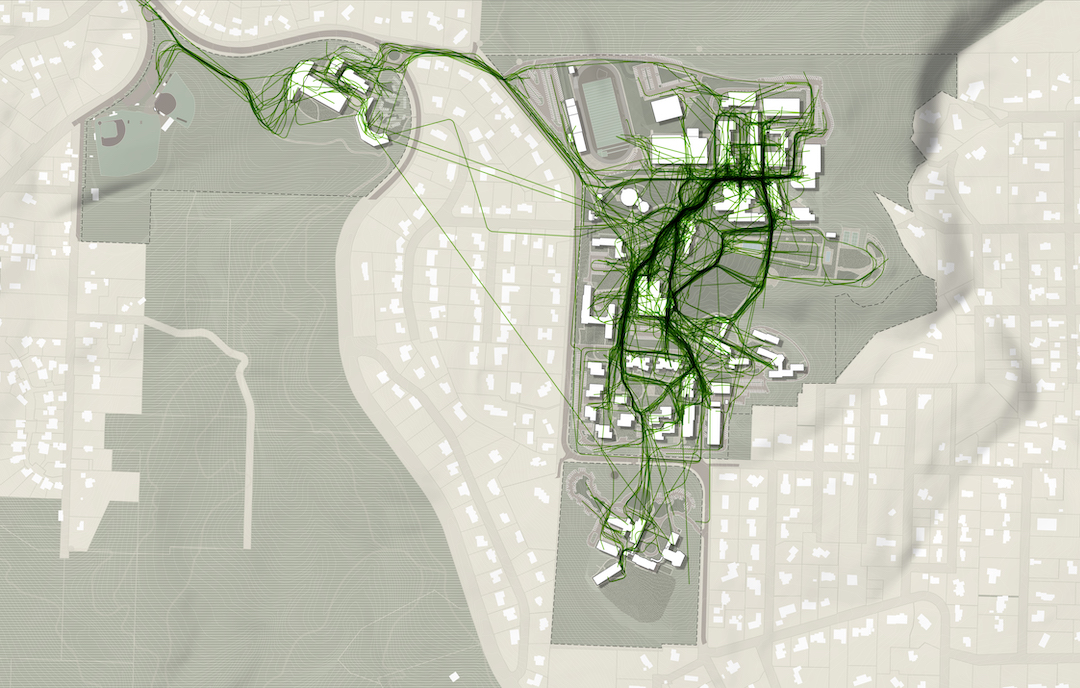

One of the main tools Sasaki uses to mitigate the informal desire path is a proprietary program developed by its in-house data and design tools group called CoMap. This collaborative mapping program generates a spatial visualization of how people experience a campus or region. When used at institutions, CoMap’s survey function allows campus communities to add notes about places or trace routes on a map of the campus. Sasaki then uses the data to inform planning recommendations.

“Many times the paths most traveled by students are not necessarily formally designed paths. The planning recommendation might therefore be to strengthen a desire line path by widening it, resurfacing it, removing an impediment, or lining it with active uses,” says Tyler Patrick, AICP, Principal, Chair of Planning and Urban Design on Board of Directors, and Planner with Sasaki. “For example, sometimes we find that service drives that are designed for vehicles are also heavily used by pedestrians, so we can instead redesign the path as more of a shared-use amenity, with aesthetic improvements to paving, lighting, etc.”

At one university, Sasaki used CoMap to learn that the formal entry to the campus was rarely used and the service drive actually served as the primary pedestrian route into campus. The design team took this information and reoriented the campus and created a new “front door” where the service drive used to be, with service access still accommodated, but in a more understated manner.

Sasaki also used CoMap in a master planning effort the firm led for Lewis & Clark College. The CoMap survey highlighted a strong north-south pedestrian route along an existing road. In response to the user feedback from CoMap, Sasaki turned the route into a primary pedestrian promenade on campus, surrounded by new residential and student life facilities.

CoMap is just one strategy the firm uses to create efficient plans without any informal desire paths. “We employ a range of strategies that include analyzing the existing system of pathways (what forms of mobility they support, their width, condition, amenities, etc.); collecting a variety of data (for instance, looking at where the concentration of classrooms is, as well as classroom utilization, to see key areas between which students may be moving); and conducting interviews and surveys to learn how pathways are used, deficiencies in the overall system, and desire paths that have not been formalized,” says Patrick.

Desire paths do not always equal good design

Just because an informal desire path appears, it does not mean it should always be formalized. Especially if the path is in direct conflict with the greater overall design scheme. “For instance, students may want to formally cross through a recreation field, but we want to maintain the field’s integrity for recreation and so we wouldn’t want to formalize that kind of desire path,” Patrick says.

Other instances may include environmental or safety concerns, such as wanting to keep a stream side riparian system intact as opposed to introducing formalized pedestrian pathways. “If a desire line promotes a path that isn’t accessible, we likely would not want to promote that movement,” adds Clauson.

The key is to balance how people want to use a given space without it turning into a free-for-all. Desire paths can, and often times do, suggest improvements for pedestrian circulation, but blindly formalizing any desire path can easily lead to a one step forward, two steps back situation. As Patrick said above, a desire path that cuts through a recreation field may prove that it is the most efficient way to traverse a campus, but formalizing it would certainly lead to more complaints about a now fractured field that is much more of an inconvenience than the lack of a formal path ever was.

As is often the case in modern design, the benefits of flexibility should never be understated. “A good campus plan should be flexible enough to accommodate evolving patterns of use and allow for the campus to integrate new ideas into the framework,” Patrick says.

The desire path, then, is representative of a larger point: There is no such thing as a perfect design, but there can be a perfectly adaptable one. Having the ability to continually adjust and formally adapt to the desires of end users is the best way to achieve the highest possible efficiency for any design.

Related Stories

Senior Living Design | May 8, 2023

Seattle senior living community aims to be world’s first to achieve Living Building Challenge designation

Aegis Living Lake Union in Seattle is the world’s first assisted living community designed to meet the rigorous Living Building Challenge certification. Completed in 2022, the Ankrom Moisan-designed, 70,000 sf-building is fully electrified. All commercial dryers, domestic hot water, and kitchen equipment are powered by electricity in lieu of gas, which reduces the facility’s carbon footprint.

Multifamily Housing | May 8, 2023

The average multifamily rent was $1,709 in April 2023, up for the second straight month

Despite economic headwinds, the multifamily housing market continues to demonstrate resilience, according to a new Yardi Matrix report.

BIM and Information Technology | May 8, 2023

3 ways computational tools empower better decision-making

NBBJ explores three opportunities for the use of computational tools in urban planning projects.

University Buildings | May 5, 2023

New health sciences center at St. John’s University will feature geothermal heating, cooling

The recently topped off St. Vincent Health Sciences Center at St. John’s University in New York City will feature impressive green features including geothermal heating and cooling along with an array of rooftop solar panels. The geothermal field consists of 66 wells drilled 499 feet below ground which will help to heat and cool the 70,000 sf structure.

Office Buildings | May 4, 2023

In Southern California, a former industrial zone continues to revitalize with an award-winning office property

In Culver City, Calif., Del Amo Construction, a construction company based in Southern California, has completed the adaptive reuse of 3516 Schaefer St, a new office property. 3516 Schaefer is located in Culver City’s redeveloped Hayden Tract neighborhood, a former industrial zone that has become a technology and corporate hub.

Mass Timber | May 3, 2023

Gensler-designed mid-rise will be Houston’s first mass timber commercial office building

A Houston project plans to achieve two firsts: the city’s first mass timber commercial office project, and the state of Texas’s first commercial office building targeting net zero energy operational carbon upon completion next year. Framework @ Block 10 is owned and managed by Hicks Ventures, a Houston-based development company.

Market Data | May 2, 2023

Nonresidential construction spending up 0.7% in March 2023 versus previous month

National nonresidential construction spending increased by 0.7% in March, according to an Associated Builders and Contractors analysis of data published today by the U.S. Census Bureau. On a seasonally adjusted annualized basis, nonresidential spending totaled $997.1 billion for the month.

Hotel Facilities | May 2, 2023

U.S. hotel construction up 9% in the first quarter of 2023, led by Marriott and Hilton

In the latest United States Construction Pipeline Trend Report from Lodging Econometrics (LE), analysts report that construction pipeline projects in the U.S. continue to increase, standing at 5,545 projects/658,207 rooms at the close of Q1 2023. Up 9% by both projects and rooms year-over-year (YOY); project totals at Q1 ‘23 are just 338 projects, or 5.7%, behind the all-time high of 5,883 projects recorded in Q2 2008.

Architects | May 1, 2023

HOK names Eli Hoisington and Susan Klumpp Williams as Co-CEOs

HOK has appointed Eli Hoisington, AIA, LEED AP, and Susan Klumpp Williams, AIA, LEED AP, as its new co-chief executive officers, succeeding Bill Hellmuth, FAIA, LEED AP, who passed away on April 6, shortly after his scheduled retirement.

Multifamily Housing | May 1, 2023

A prefab multifamily housing project will deliver 200 new apartments near downtown Denver

In Denver, Mortenson, a Colorado-based builder, developer, and engineering services provider, along with joint venture partner Pinnacle Partners, has broken ground on Revival on Platte, a multifamily housing project. The 234,156-sf development will feature 200 studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom apartments on eight floors, with two levels of parking.