On June 6, the first phase in the construction of the new Children’s Hospital at Erlanger in Chattanooga, Tenn., broke ground. When it opens next year, this three-story, 90,000-sf, $40 million outpatient center—which HKS designed and McCarthy Building Companies is building—will encompass 72 exam rooms, 21 specialty pediatric clinics, lab and imaging services, and a pharmacy.

Sick or injured kids who come through the center’s front entrance and lobby might forget, if for a moment, they’re in a hospital. Those areas will feature an authentic 1891 steam engine donated by the Tennessee Valley Railway Museum, a 30-year-old fire truck cab from the Creative Discovery Museum, a pink tow truck donated by the International Towing and Recovery Museum, a tree house provided by the local tourist attraction Rock City, and kite-like gliders suspended from the ceiling.

Such decorative flourishes are among the positive distractions this and other new and renovated children’s hospitals are adding to mitigate fears and anxieties of patients and their families.

“It used to be that you could put a couple of toys in the lobby and that was enough,” says Randy Beckwith, AIA, LEED AP, Project Manager with Carrier Johnson + Culture, whose resume includes recent work on the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford in Palo Alto, Calif. “Now, architecture is doing what it has always done best: affect people’s lives, their moods.”

That influence, though, doesn’t stop at shiny objects, brighter colors and signage, or themed floors. AEC sources says their healthcare clients are focused on giving young patients a level of control over their surroundings, and a way to maintain some continuity, while hospitalized, with relatives and friends.

“Most children’s hospitals will have areas of respite for patients to enjoy recreation or retreat to a garden or sitting area, resources to continue school while in the hospital, and similar children’s activities to make their stay more enjoyable,” says Dan Spinetto, VP and Regional Operations Manager with Brasfield & Gorrie. “It is important for the construction team to understand the purposes of those areas, and appreciate that they are as important to the care of the patient as the procedure rooms.”

When HDR takes on a children’s hospital project, it pursues a design philosophy “that takes into account understanding human nature and empathizing with what children and their families are experiencing,” says Brian Zabloudil, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, Senior Healthcare Planner and Children’s Services Leader with HDR.

The firm’s latest work in this sector includes the 340,000-sf expansion of the Children’s of Mississipp–Batson Children’s Hospital, in Jackson, and the 450,000-sf expansion of the Children’s Hospital and Medical Center in Omaha, Neb. Each has been designed “with a particular sense of place and scale,” says Zabloudil.

Children’s hospitals, in fact, have become “incubators for hospital design innovation,” says Uma Ramanathan, AIA, Principal with Shepley Bulfinch, which has produced a report, Designing for Children, that identifies seven factors that make these daunting environments less intimidating.

Located on the fifth-floor roof of the East Tennessee Children’s Hospital in Knoxville, this 4,500-sf roof garden offers a quiet escape for patients and family members. The curvilinear design was inspired by the Tennessee River and the native riverfront landscape. CRJA-IBI Group designed the space. Denise Retallack.

Located on the fifth-floor roof of the East Tennessee Children’s Hospital in Knoxville, this 4,500-sf roof garden offers a quiet escape for patients and family members. The curvilinear design was inspired by the Tennessee River and the native riverfront landscape. CRJA-IBI Group designed the space. Denise Retallack.

CREATING A SENSE OF NORMALCY

Children’s hospitals differ from other healthcare facilities in several ways. For one thing, “when you’re treating a child, you’re really treating the whole family,” observes Jocelyn Stroupe, IIDA, CHID, EDAC, ASID, Director of Healthcare Interiors with CannonDesign. So any design should strive to create “a sense of normalcy,” says Stroupe, especially for inpatient care, where kids have longer lengths of stay.

That often translates into designs that perpetuate routines to make patients feel more comfortable, less stressed. More hospitals allow patients to control room environments, such as lighting. And children’s hospitals often include learning areas and even classrooms where patients can keep up with their school work.

At one of CannonDesign’s recent projects, the St. Louis Children’s Special Care Center in Town & Country, Mo, an outpatient facility, the firm and hospital worked in tandem to examine how children interact with and perceive healthcare spaces. The facility’s design focused on providing opportunities to play, socialize, fantasize, and explore. Stroupe adds that in-patient rooms at the hospital's main campus allow patients to personalize their environments with artwork either they or their friends create.

Writable surfaces hang from patient room walls, sized to accommodate the age ranges that pediatric care touches.

Children’s hospitals treat a gamut of patients that runs from newborns and young kids to teenagers and even adults with chronic childhood illnesses. The charge for Building Teams, then, “is to create an environment that is friendly and appealing to a preschooler as well as a high school kid,” says Brasfield & Gorrie’s Spinetto. He and other AEC sources say that common areas with multiple features that include educational games and diversions can bridge the hospital’s patient-age divide.

Given that some patients with chronic illnesses or injuries that require therapy or treatment might be returning to the hospital down the road, pediatric-care design must consider a patient’s stages of psychosocial development, observes Joshua Theodore, ACHE, EDCA, VP and Global Health Practice Leader with Leo A Daly. “The building should lead them on a path to recovery,” he says.

Sometimes that initial leg of that path can be a hike. Children’s hospitals often serve large geographic regions. Some families must travel great distances to provide their child with the care they need, and to stay with them long-term—which is generally considered an important therapeutic element in the patient’s recovery. Hospitals are recognizing the need to accommodate those families for longer stays.

Ronald McDonald House Charities of Connecticut and Western Massachusetts on July 1 opened a 30,000-sf, $11.35 million Ronald McDonald House across the street from Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital in New Haven, Conn. Ronald McDonald Houses typically accommodate families whose children are the sickest, and who travel the farthest distances for care. “Most of the families here are Latino, have large families, and aren’t affluent,” says Ron Cooper, AIA, NCARB, Principal with Svigals + Partners, which designed this project. A typical stay for a family at a Ronald McDonald House is four weeks, he says.

The new building in New Haven replaces an older Ronald McDonald House a few miles away. It includes 18 suites and two respite rooms. Cooper says this is a three-phase project that could eventually build out to a total of 42 suites.

Hospitals themselves are being designed with larger patient rooms and family-friendlier amenities.

The patient rooms at the Children’s Hospital at Erlanger will range from 280 to 350 sf, double the size of the rooms in its older hospital, says Bruce Komiske, MHA, FACHE, VP of New Hospital Design and Construction for Erlanger Health System.

Kevin Kuntz, President of McCarthy’s Southeast division in Atlanta, thinks it’s good that rooms are being made spacious enough for relatives to stay with patients longer because “patients are more willing to talk with family members about their illnesses or discomforts than with the hospital staff.”

The Medical University of South Carolina’s (MUSC) 625,000-sf Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital and Pearl Tourville Women’s Pavilion, currently under construction in Charleston, S.C., and scheduled to open in October 2019, will include ICU rooms that are double the size of rooms in its older facility, and other patient rooms that are 80% larger. Families staying for extended periods will have access to kitchens, showers, and washers and dryers. The new building will have enhanced Wi-Fi capacity. A conference room on each patient floor will allow medical teams to collaborate and discuss patient issues with family members.

Children’s hospitals seem to be paying particular attention to improving familial experiences in their neonatal areas, with an eye toward letting mothers stay closer to newborns longer, and families to remain in close proximity to mothers after childbirth.

The Children’s Hospital and Medical Center in Omaha, which is scheduled for completion in 2021, will include a fetal care center with side-by-side operating rooms, so specialists can perform C-sections and then bring newborns into the second OR if there are complications, explains HDR’s Zabloudil.

The $75 million, 271,120-sf expansion of the East Tennessee Children’s Hospital in Knoxville, which opened in April, includes a 44-bed NICU designed to allow family members to be present 24/7 “to promote critically important bonding” with newborns, says Keith Goodwin, the hospital’s President and CEO. That space includes a suite with a kitchen, resource center, and walk-out roof garden.

Ramanathan of Shepley Bulfinch, the design architect on the project, says her firm employed gaming technology to figure out how to get more natural light into the NICU rooms, which are organized into clusters to make it easier for patients’ families to interact with each other and with the hospital staff.

MUSC’s children’s hospital will feature a neonatal center where mothers and sick babies can stay together, as long as the newborn’s gestation is least 32 weeks. The only other hospital in the U.S. offering neonatal couplet care is Catholic Medical Center in Manchester, N.H., says Robin Mutz, MPPM, BSN, RNC, NEA-BC, Executive Nursing Director of the MUSC children’s hospital.

In late 2016, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston renovated nine sleep rooms, where parents can stay to rest, shower, and do laundry while their children receive treatment at the hospital. These rooms serve more than 2,300 families per year. Brasfield & Gorrie, the project’s CM, teamed with architect Crosby Design Group on the project. Nicole W Photography.

In late 2016, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston renovated nine sleep rooms, where parents can stay to rest, shower, and do laundry while their children receive treatment at the hospital. These rooms serve more than 2,300 families per year. Brasfield & Gorrie, the project’s CM, teamed with architect Crosby Design Group on the project. Nicole W Photography.

Getting Families involved in the design process

Hospital administrators and AEC teams are seeking input from patients’ families as never before. HDR, for one, “relies pretty heavily” on family focus groups when it’s designing hospitals, says Zabloudil.

Twenty-six family members of current and past patients were involved for more than a year in the design phase of MUSC’s new children’s hospital—with between one and four family members sitting in on every weekly architectural meeting about clinical spaces.

Among those parents was Kelly Loyd, whose twin daughters were born premature and had to stay at the hospital for weeks following their birth. Loyd chairs MUSC’s Family Advisory Council and was part of the feasibility and steering committees during the design of the new hospital.

“Perkins+Will [the project’s design architect] remarked in a blog that it wasn’t used to that kind of involvement by families on such a project,” recounts Loyd, with evident satisfaction.

Those families didn’t win every battle over design changes. But some of their victories were notable. Loyd recalls one woman who was involved in the design of the cardiac room. Initially that design called for an open floor plan. But this woman—who had lost a child to illness—wrote a letter to the council stating that the design wouldn’t give families the privacy they needed to grieve. Her letter was forwarded to the hospital’s medical director, who read it at the next meeting and then said the design would defer to this woman’s request and would include private rooms.

At the Children’s Hospital at Erlanger, Komiske says he originally wanted to suspend a half-size medevac helicopter from the lobby’s ceiling as a cool feature that connected with one of that facility’s signature services. But one parent said during a design meeting that while the real medevac saved his son’s life, his family didn’t want to be reminded of the experience every time they walked into the building. “That’s when the team decided to suspend hang gliders instead,” says Komiske.

VR in Pediatric care: pros and cons

Before the design of the Children’s Hospital at Erlanger was completed, McCarthy built 300-sf mockups of patient rooms, which different user groups—staff, families, former patients—could walk through and take notes for possible changes. Will Gaither, McCarthy’s Senior Project Manager, says suggestions included more USB ports and cabinets sized so they don’t impede strollers coming into and being stored in the room.

“This was better than VR, which we’ve also used, because it allows people to see colors, fabrics, and so forth,” says Gaither.

AEC firms regularly use virtual reality to assist their clients in understanding design nuances or construction choices. And a growing number of hospitals are incorporating VR into their patient care. Seattle Children’s Hospital recently teamed with the startup Pear Med to develop VR and augmented reality software for clinical diagnosis and patient communication. Pediatric cardiologists at the Children’s Heart Center at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford are using immersive VR technology to explain complex congenital heart defects.

MUSC’s children’s hospital uses VR technology to provide autistic kids with “virtual visits” to the hospital and some of its procedure and testing rooms “so there are no surprises” when they are admitted, says Mutz. Other hospitals use VR to distract kids who require frequent injections.

But some AEC sources aren’t sold yet on VR as a substitute for simulation rooms that hospitals have long used to prepare children for what it’s like to be rolled into an MRI tube or onto an operating table. Shepley Bulfinch’s Ramanathan, for one, thinks real simulation rooms are still better than any virtual alternative. “What hospitals are missing these days is a sense of touch, especially for a child,” says Ramanathan. “Plus, a lot of people don’t understand VR.”

The University of Connecticut’s Brain Imaging Research Center, which maps oxygen sensors in the brains of children with disabilities, includes a 10x16-foot simulation room with an ersatz MRI machine that physicians use to explain to kids what’s going to happen “and to gain their trust,” says Cooper of Svigals + Partners, which renovated the 4,500-sf center a couple of years ago.

But just as technology is now integral to medicine, surgery, and rehab, so too is it likely to play a bigger role in helping children’s hospitals create immersive experiences that take patients’ minds off of their problems.

The University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital in Iowa City, which opened in February, recently debuted in its lobby a 32-foot-long, curved-screen theater that, using Microsoft’s Kinect technology, runs two interactive games: “Eagle’s Flight,” where kids use their arms to control the flight of birds across the U.S. to view landmarks like Mount Rushmore; and “Story in the Stars,” which brings three stories to life as constellations. The theater is accessible to children in wheelchairs and with limited mobility.

Tom Collins, Chief Operating Officer of Dimensional Innovations, which developed the theater, sees diversionary tactics like this becoming more prevalent in children’s hospitals as ways to help sick kids “escape from the hospital without physically leaving the building.” He adds that a basic system can be installed for under six figures.

Ramanathan says her firm has been experimenting with “digital distractions” for children’s hospitals and has incorporated some of them into early designs. One recent hospital project includes a huge digital wall “that has become the first stop for kids.” And it operates without any touching required, which Ramanathan says is an important consideration in high-acuity settings where infection control is a priority.

Related Stories

| Oct 13, 2010

Prefab Trailblazer

The $137 million, 12-story, 500,000-sf Miami Valley Hospital cardiac center, Dayton, Ohio, is the first major hospital project in the U.S. to have made extensive use of prefabricated components in its design and construction.

| Oct 13, 2010

Hospital tower gets modern makeover

The Wellmont Holston Valley Medical Center in Kingsport, Tenn., expanded its D unit, a project that includes a 243,443-sf addition with a 12-room operating suite, a 36-bed intensive care unit, and an enlarged emergency department.

| Oct 13, 2010

Hospital and clinic join for better patient care

Designed by HGA Architects and Engineers, the two-story Owatonna (Minn.) Hospital, owned by Allina Hospitals and Clinics, connects to a newly expanded clinic owned by Mayo Health System to create a single facility for inpatient and outpatient care.

| Oct 13, 2010

Maryland replacement hospital expands care, changes name

The new $120 million Meritus Regional Medical Center in Hagerstown, Md., has 267 beds, 17 operating rooms with high-resolution video screens, a special care level II nursery, and an emergency room with 53 treatment rooms, two trauma rooms, and two cardiac rooms.

| Oct 13, 2010

Cancer hospital plans fifth treatment center

Construction is set to start in December on the new Cancer Treatment Centers of America’s $55 million hospital in Newnan, Ga. The 225,000-sf facility will have 25 universal inpatient beds, two linear accelerator vaults, an HDR/Brachy therapy vault, and a radiology and imaging unit.

| Oct 13, 2010

New health center to focus on education and awareness

Construction is getting pumped up at the new Anschutz Health and Wellness Center at the University of Colorado, Denver. The four-story, 94,000-sf building will focus on healthy lifestyles and disease prevention.

| Oct 13, 2010

Community center under way in NYC seeks LEED Platinum

A curving, 550-foot-long glass arcade dubbed the “Wall of Light” is the standout architectural and sustainable feature of the Battery Park City Community Center, a 60,000-sf complex located in a two-tower residential Lower Manhattan complex. Hanrahan Meyers Architects designed the glass arcade to act as a passive energy system, bringing natural light into all interior spaces.

| Oct 12, 2010

Holton Career and Resource Center, Durham, N.C.

27th Annual Reconstruction Awards—Special Recognition. Early in the current decade, violence within the community of Northeast Central Durham, N.C., escalated to the point where school safety officers at Holton Junior High School feared for their own safety. The school eventually closed and the property sat vacant for five years.

| Sep 13, 2010

Palos Community Hospital plans upgrades, expansion

A laboratory, pharmacy, critical care unit, perioperative services, and 192 new patient beds are part of Palos (Ill.) Community Hospital's 617,500-sf expansion and renovation.

| Sep 13, 2010

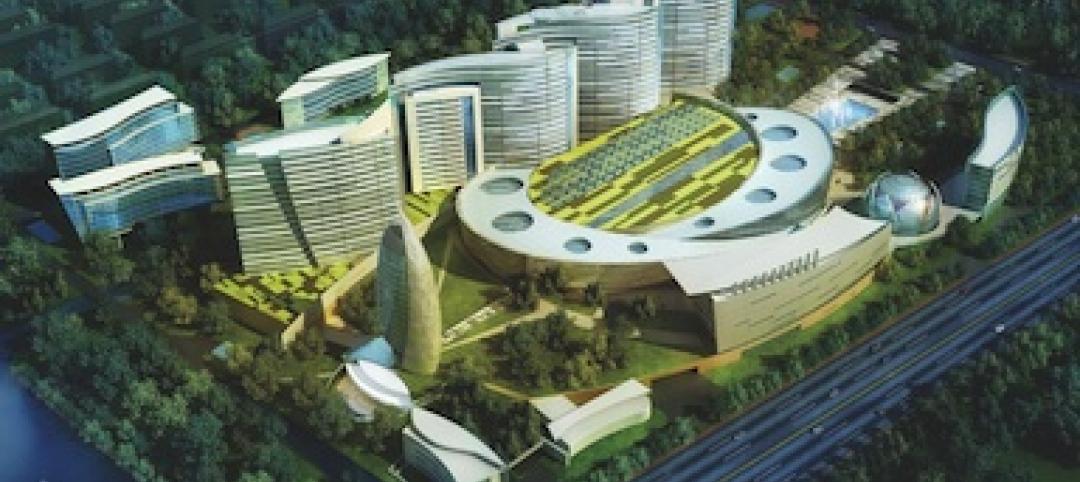

China's largest single-phase hospital planned for Shanghai

RTKL's Los Angles office is designing the Shanghai Changzheng New Pudong Hospital, which will be the largest new hospital built in China in a single phase.