The benefits of having a sports facility in a community are many—from a shared sense of public pride to increased job opportunities to enhanced real estate values—but perhaps surprisingly, immediate profitability is not among them. Whether minor league ballpark or Olympic-caliber stadium, the economics of athletic facilities is an intricate business, involving franchise fees, broadcast agreements, sponsorships, public funding, licensing issues, and more. Because of this complicated scenario, a realistic understanding of the budget is critical, and must be determined well before the architectural design phase begins.

Cost modeling, an algorithm-based process of estimating the complex expenses of a construction project by analyzing fixed and variable factors, can provide the clarity and direction that get a project off on the right financial foot, putting the facility development on the road to profitability. While there are two established approaches to this—one focuses on cost-per-seat, the other on cost-per-square-foot—there are compelling arguments why relying on just one of these methods may lead to inaccurate conclusions.

While there are two established approaches to this—one focuses on cost-per-seat, the other on cost-per-square-foot—there are compelling arguments why relying on just one of these methods may lead to inaccurate conclusions.

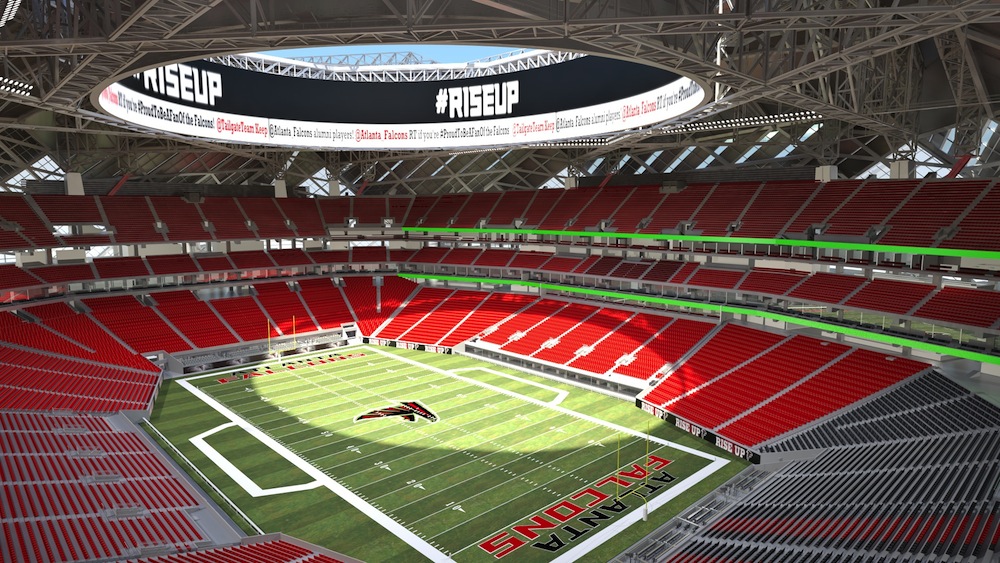

The reason for this is apparent to anyone who has walked through an arena turnstile in the past five years: Modern athletic facility design is far from standardized. What was once simply a playing field surrounded by bleachers, today’s facilities have evolved into entertainment destinations where the competition is not just between teams on the gridiron, diamond, or rink, but also for customers at the multitude of concessions that now populate these venues.

Restaurants and bars, luxury suites, and fan-experience features all make significant contributions to the bottom line of the facility’s business. Such diverse amenities frequently require sophisticated technologies that go beyond the normal parameters of design, so it follows that they also defy conventional cost-modeling techniques.

As sports seasons are limited in length, facility operators look to supplement their income by scheduling revenue-generating events throughout the entire year. To do so, the venue must be designed to accommodate a variety of activities, from concerts to conventions. When a building is multi-functional and doesn’t fit a well-defined profile of a single-purpose structure, using cost-modeling with a narrow focus simply isn’t a suitable approach.

It’s not just the bells and whistles aspects of arenas that keep cost-modeling experts on their toes; the basic building program can prove resistant to seat- or square-foot-based study, as well. Something as fundamental as the location of a facility can dictate certain architectural measures that disrupt strictly formulaic analysis. Examples of such circumstances abound: facilities in earthquake-prone regions will require seismic engineering; those in northern climes must contend with snow loads on the roof; where extreme heat and humidity prevail, solar control might take the form of an expensive retractable roof or a more affordable passive shading system. All these present estimating challenges which cannot be resolved though a single mode of cost-modeling without risk.

Paradoxically, even the seating plan may confound traditional cost-modeling practices. Particularly with the increasing emphasis on luxury boxes as a source of revenue, the amount of general admission seating has become an economically fraught issue.

Responsive cost models are key

As early as possible during conceptual design stages, a responsive cost model should be assembled so that building elements can be isolated, interrogated, and priced individually. Fortunately, most facility designers will have sufficient experience to be able to respond constructively to detailed design questions asked early on in the process. Accordingly, an effective cost model should be organized by building elements—from foundations systems to interior finishes to A/V and special tech systems—in order to create comprehensive cost scenarios.

There are significant advantages to implementing a more detailed cost modeling technique. Unique facility design and cost challenges, which are often overlooked in comparative cost modeling, can be illuminated and addressed early on. At early stages, the conceptual design is still quite flexible and malleable and responses to cost issues can be modelled and priced in relatively short order if the baseline cost model has been properly prepared. And, perhaps most important, conversations about the facility costs can be addressed with specific data rather than conjecture and biased opinions.

Obviously this process places demands on design and project teams, which are more commonly encountered at later stages of the process. However, an added virtue of implementing discovery early on is that it engages the entire team in an informed discussion about costs at a point in the design where changes can be affected with minimal effort and maximum impact.

Cost modeling is a powerful tool for planning sports facilities, but to reap the rewards it offers, it’s important to understand the limits, as well as the capabilities, of the process. With architects continuously upping the ante on facility designs, relying on per-square-foot methods can be a costly mistake. Responsive modeling is critical. Experience and strong relationships are key to engendering full “buy-in” for these methods with all stakeholders and team members. But when everyone is on board, this process can actually promote and improve trust, foster teamwork, and create a sense of shared responsibility to ensure a successful project outcome.

About Peter Knowles: Peter Knowles is executive vice president of Rider Levett Bucknall North America. Based in Denver, he is a member of Rider Levett Bucknall’s senior leadership team responsible for operations of the North American practice. Peter joined the firm in 1987. As a Chartered Quantity Surveyor with over 30 years of experience, he has particular expertise in healthcare and sports facilities, and has worked on aviation, commercial, educational, healthcare, hospitality, mission critical, research and technology, and public assembly projects in the United States, Asia, and Europe. Peter specializes in the management of construction cost and time of projects. A Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveys, Peter is also a member of the Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors and the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering.

About Steve Kelly: Steve Kelly is an associate principal at Rider Levett Bucknall and leads the firm’s Seattle office. With more than 29 years of experience in cost management, Steve has worked on behalf of building contractors and cost consulting firms providing his expertise in preparing bills of quantities, analyzing projects by functional component, evaluation of change orders and post construction management control. In addition to his specialized expertise in the sports sector, Steve has worked on numerous projects in sectors ranging from education and hospitality to healthcare infrastructure and commercial. He is also a Member of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (MRICS).

Related Stories

| Nov 3, 2010

Sailing center sets course for energy efficiency, sustainability

The Milwaukee (Wis.) Community Sailing Center’s new facility on Lake Michigan counts a geothermal heating and cooling system among its sustainable features. The facility was designed for the nonprofit instructional sailing organization with energy efficiency and low operating costs in mind.

| Nov 3, 2010

Recreation center targets student health, earns LEED Platinum

Not only is the student recreation center at the University of Arizona, Tucson, the hub of student life but its new 54,000-sf addition is also super-green, having recently attained LEED Platinum certification.

| Oct 13, 2010

New health center to focus on education and awareness

Construction is getting pumped up at the new Anschutz Health and Wellness Center at the University of Colorado, Denver. The four-story, 94,000-sf building will focus on healthy lifestyles and disease prevention.

| Oct 13, 2010

Community center under way in NYC seeks LEED Platinum

A curving, 550-foot-long glass arcade dubbed the “Wall of Light” is the standout architectural and sustainable feature of the Battery Park City Community Center, a 60,000-sf complex located in a two-tower residential Lower Manhattan complex. Hanrahan Meyers Architects designed the glass arcade to act as a passive energy system, bringing natural light into all interior spaces.

| Oct 13, 2010

Community college plans new campus building

Construction is moving along on Hudson County Community College’s North Hudson Campus Center in Union City, N.J. The seven-story, 92,000-sf building will be the first higher education facility in the city.

| Oct 12, 2010

Owen Hall, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich.

27th Annual Reconstruction Awards—Silver Award. Officials at Michigan State University’s East Lansing Campus were concerned that Owen Hall, a mid-20th-century residence facility, was no longer attracting much interest from its target audience, graduate and international students.

| Oct 12, 2010

Building 13 Naval Station, Great Lakes, Ill.

27th Annual Reconstruction Awards—Gold Award. Designed by Chicago architect Jarvis Hunt and constructed in 1903, Building 13 is one of 39 structures within the Great Lakes Historic District at Naval Station Great Lakes, Ill.

| Sep 16, 2010

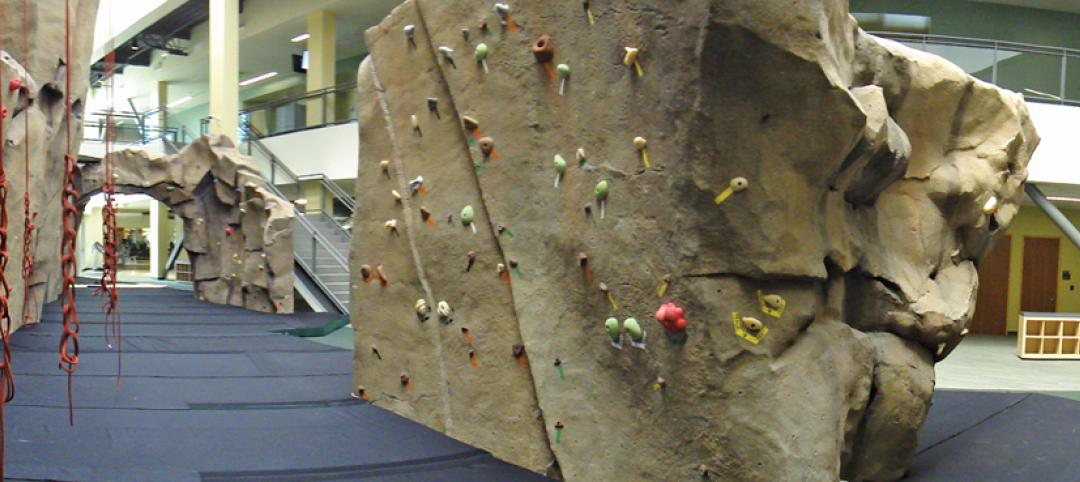

Green recreation/wellness center targets physical, environmental health

The 151,000-sf recreation and wellness center at California State University’s Sacramento campus, called the WELL (for “wellness, education, leisure, lifestyle”), has a fitness center, café, indoor track, gymnasium, racquetball courts, educational and counseling space, the largest rock climbing wall in the CSU system.

| Sep 13, 2010

Stadium Scores Big with Cowboys' Fans

Jerry Jones, controversial billionaire owner of the Dallas Cowboys, wanted the team's new stadium in Arlington, Texas, to really amp up the fan experience. The organization spent $1.2 billion building a massive three-million-sf arena that seats 80,000 (with room for another 20,000) and has more than 300 private suites, some at field level-a first for an NFL stadium.

| Aug 11, 2010

JE Dunn, Balfour Beatty among country's biggest institutional building contractors, according to BD+C's Giants 300 report

A ranking of the Top 50 Institutional Contractors based on Building Design+Construction's 2009 Giants 300 survey. For more Giants 300 rankings, visit http://www.BDCnetwork.com/Giants