Last December, Prince George’s County in Maryland became the first K-12 school district in the nation to partner with the private sector to bundle and finance a six-school delivery program. The public-private consortium included Fengate Capital Management, Gilbane’s development and building companies, designer and architect Stantec, and maintenance services provider Honeywell. JLL was Prince George’s Public School’s financial advisor.

The new schools will be ready for the 2023-24 school year, and add 8,000 new seats across five middle schools and one K-8 school. The school district is expected to save $174 million in deferred maintenance and construction costs.

Financing the construction and renovation of public schools continues to be a major challenge that, in many states, hinges on voters approving bond issues or taxes. For most of America’s 13,000-plus school districts, the private sector is an untapped source for funding.

“At the moment, there is no common definition of a P3 in the U.S., there is no centralized governing body overseeing P3s, and there is an extremely limited breadth of experience in [the] K-12 sector,” states Braisford & Dunlavey, an education planning, development, and management consultant based in Washington, D.C., which has released a free, 40-page guide to K-12 public-private partnerships (P3s).

The guide notes that the National Council of Public-Private Partnerships identifies 18 different legal and financial P3 structures, and each agreement is sui generis to the partnership, or deal. “In K-12, we expect the range of employed structures to be much smaller. Still, each partnership will be unique.”

SEVERAL MOTIVATIONS CITED

The guide cautions that P3s are complex deal structures, and there is no simple pro/con checklist for school districts considering entering into them.

Possible motivations might include accelerating the schedule for delivery of one or more school projects. (That was the primarily factor driving Prince George’s County’s P3.) Reallocating risk and lowering construction costs are two other reasons why P3s might make sense. But school districts must also realize there’s a cost to shifting risk to the private sector in terms of capital lending, legal and development fees, and other compensation.

“P3s aren’t employed for fun,” cautions the guide. “They’re neither simple nor free, and can face a resistant community. If they’re employed, it means there’s a problem that needs solving and it’s best solved with a P3.”

And because K-12 districts typically lack revenue-generating components, the full range of P3s isn’t available to them. “We expect most large-scale projects in K-12 will resemble availability payment agreements/concessionaire agreements, in which the development team designs, builds, finances, operates, and maintains a building that it ‘makes available’ to the district in exchange for availability payments (paid annually, throughout the life of the agreement),” the guide states.

For a P3 to be a viable funding solution, enabling legislation must be in place, the guide states. And for large-scale projects to “pencil out,” the guide recommends that operations and maintenance be key components to most deals.

IS YOUR DISTRICT A GOOD P3 CANDIDATE?

Braisford & Dunlavey states that certain districts fit the profile for considering P3s:

•A large school district facing financially crippling deferred maintenance. “Good news for these projects: Bigger districts tend to have bigger budgets. That can attract developers and other private partners for a large-scale P3. While a smaller project isn’t doomed, it’s less likely.”

•A large school district facing growing enrollment.

•A school district (small or large) with land it can give up, and whose needs it cannot meet on its own. The guide suggests that this type of revenue model is an “easier” P3, but the district still needs to convince the public that this is the best use of the land.

•A school district with a visionary leader who steps up and says, “Enough is enough.” The guide says that projects need champions to navigate approvals, manage stakeholder engagement, and think strategically.

The attributes of any good engagement, according to Braisford & Dunlavey, start with a clear definition of expected outcomes. These pacts also require sufficient time to hash out the deal’s structure and legal details. Stakeholders need to be “true partners” invested in each other’s success, and always honest.

The school district should define the quality of the project’s design and construction, but also be flexible enough to allow its private-sector partners to achieve those parameters.

Related Stories

K-12 Schools | Apr 10, 2024

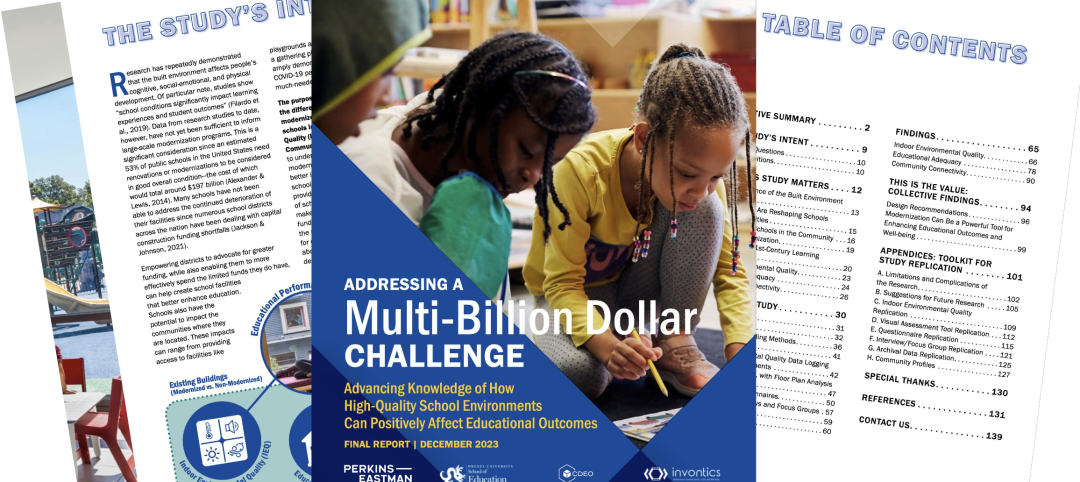

Surprise, surprise: Students excel in modernized K-12 school buildings

Too many of the nation’s school districts are having to make it work with less-than-ideal educational facilities. But at what cost to student performance and staff satisfaction?

K-12 Schools | Apr 1, 2024

High school includes YMCA to share facilities and connect with the broader community

In Omaha, Neb., a public high school and a YMCA come together in one facility, connecting the school with the broader community. The 285,000-sf Westview High School, programmed and designed by the team of Perkins&Will and architect of record BCDM Architects, has its own athletic facilities but shares a pool, weight room, and more with the 30,000-sf YMCA.

Security and Life Safety | Mar 26, 2024

Safeguarding our schools: Strategies to protect students and keep campuses safe

HMC Architects' PreK-12 Principal in Charge, Sherry Sajadpour, shares insights from school security experts and advisors on PreK-12 design strategies.

K-12 Schools | Mar 18, 2024

New study shows connections between K-12 school modernizations, improved test scores, graduation rates

Conducted by Drexel University in conjunction with Perkins Eastman, the research study reveals K-12 school modernizations significantly impact key educational indicators, including test scores, graduation rates, and enrollment over time.

K-12 Schools | Feb 29, 2024

Average age of U.S. school buildings is just under 50 years

The average age of a main instructional school building in the United States is 49 years, according to a survey by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). About 38% of schools were built before 1970. Roughly half of the schools surveyed have undergone a major building renovation or addition.

Construction Costs | Feb 22, 2024

K-12 school construction costs for 2024

Data from Gordian breaks down the average cost per square foot for four different types of K-12 school buildings (elementary schools, junior high schools, high schools, and vocational schools) across 10 U.S. cities.

K-12 Schools | Feb 13, 2024

K-12 school design trends for 2024: health, wellness, net zero energy

K-12 school sector experts are seeing “healthiness” for schools expand beyond air quality or the ease of cleaning interior surfaces. In this post-Covid era, “healthy” and “wellness” are intersecting expectations that, for many school districts, encompass the physical and mental wellbeing of students and teachers, greater access to outdoor spaces for play and learning, and the school’s connection to its community as a hub and resource.

K-12 Schools | Jan 25, 2024

Video: Research-based design for K-12 schools

Two experts from national architecture firm PBK discuss how behavioral research is benefiting the design of K-12 schools in Texas, Florida, and other states. Dan Boggio, AIA, LEED AP, NCARB, Founder & Executive Chair, PBK, and Melissa Turnbaugh, AIA, NCARB, Partner & National Education & Innovation Leader, PBK, speak with Robert Cassidy, Executive Editor, Building Design+Construction.

K-12 Schools | Jan 8, 2024

Video: Learn how DLR Group converted two big-box stores into an early education center

Learn how the North Kansas City (Mo.) School District and DLR Group adapted two big-box stores into a 115,000-sf early education center offering services for children with special needs.

Designers | Jan 3, 2024

Designing better built environments for a neurodiverse world

For most of human history, design has mostly considered “typical users” who are fully able-bodied without clinical or emotional disabilities. The problem with this approach is that it offers a limited perspective on how space can positively or negatively influence someone based on their physical, mental, and sensory abilities.