|

| Perkins+Will, with Pei Partnership Architects, designed Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. |

Over the past 30 years or so, the healthcare industry has quietly super-sized its healthcare facilities. Since 1980, ORs have bulked up in size by 53%, acute-care patient rooms by 77%. The slow creep went unlabeled until recently, when consultant H. Scot Latimer applied the super-sizing moniker to hospitals, inpatient rooms, operating rooms, and other treatment and administrative spaces.

It's not just individual rooms that are bloated. Fourteen states are loaded up on more inpatient beds than population data suggests they'll need—for the next 21 years!—even as 14 other states are expected to suffer severe bed shortages (see chart, opposite). Latimer's message to hospital officials: invest wisely, because research shows that the healthcare sector will need a $2 trillion investment by 2030—$1 trillion in new construction, $1 trillion in infrastructure renewal. Super-sized spaces that do not contribute to functionality will be deemed wasteful and financially unsustainable, especially in today's economic environment.

Latimer, AIA, ACHA, a senior partner and managing director in the Denver office of Atlanta-based Kurt Salmon Associates and a past president of the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health, has made it his mission to raise awareness within the architecture community and among healthcare administrators of the need to right-size, not super-size, the nation's hospitals.

|

Latimer has nearly three decades of data—based on 76 archived projects from client work dating back to 1980—that he's worked into a persuasive argument against super-sizing. At the AIA National Conference in San Francisco last June, he drew a standing-room-only audience.

Latimer sees healthcare designers in a bind. Many of them know their hospital projects are too big, but their fees are linked to project size. “There aren't enough architects to stand up and say, 'Make it smaller and spend money more wisely.'” Architects who do speak up are often challenged by clients who want their facilities designed for what Latimer calls the worst common denominator. “Architects can't abdicate their responsibilities to the leadership of the hospitals,” says Latimer. “They need to ask the hard questions and make the tough calls about what's really justified,” he says. “You can't just design a big room to fit everything and say, 'Boom, there you go, what's next?'”

Latimer says there is a great deal of confusion about how much investment is actually required for the healthcare sector and where beds are most needed. “People are staggered by how much demand there will be for beds in the coming years,” he says. For example, based on population projections through 2030, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas will need 80% of the country's new beds. California alone will need 63,000 new beds by 2030, which is the equivalent of building a new 200-bed hospital every month for the next 25 years, says Latimer.

|

| The 365,000-sf, 181-bed Seton Medical Center-Williamson in Round Rock, Texas, is one of several recent UHS Building Solutions/HKS-designed healthcare projects that are considered right-sized. The design firm’s patient rooms average 275-300 sf, and at this hospital they come in at 291 sf. |

On the other hand, research indicates that states like New York and Pennsylvania have more than enough inpatient beds to meet demand through 2030. The logical solution, it would seem, would be to fund construction where beds are most needed. That's not the way the system works, however. Instead, many states that don't need more beds are building hospitals anyway.

As you can imagine, not everyone agrees with Latimer. They argue that designing larger spaces gives hospitals more flexibility to use a room for many different functions. But flexibility for what? asks Latimer. “Very seldom are ORs or other rooms changed into something else,” he says.

Others argue that because healthcare is getting more efficient, hospital stays are getting shorter, and more surgery is being done as outpatient procedures, the projection of $2 trillion in new construction and infrastructure is exaggerated. Latimer says, “Okay, say they're right. So, instead of $2 trillion over the next 20 years, we need $1 trillion. That's still a huge number, and there's a big responsibility to use that money wisely.”

To address that problem, Latimer says it is useful to examine three key questions: What has happened since 1980 that's led to hospital super-sizing? How is it possible to determine if increased square footage is justified? And, based on analysis of those two questions, how can hospital administrators and boards spend their capital resource funds most wisely?

A Closer Look at the Numbers

|

| Since 1980, the healthcare industry has quietly super-sized its healthcare facilities. The average patient room grew by 77%. |

Total hospital size is traditionally based on about 1,500-2,500 gross sf per inpatient bed, but that rule of thumb varies wildly at the macro level, says Latimer, so it's easier to determine justified square footage of specific spaces, such as acute-care patient rooms, ORs, or shell space.

Acute-care patient rooms have swelled in size from around 170 net sf per patient 30 years ago to an average 300-320 net sf per patient today, a 77% increase that can be ascribed in large part to the transition to single-patient rooms. Other factors include ADA requirements for patient-room bathrooms, larger patient beds (they've grown from seven feet in length to almost nine feet over the years, which has super-sized corridors so beds can be turned around), and 24-hour family space—remember the quaint days of “visiting hours”?

“We're not hearing about any new or different functions coming into the patient room indicating it should grow larger, so any additional size would grow it beyond the needs of function,” says Latimer.

|

| The average operating room increased in size by 53%. |

Operating rooms averaged 460 net sf in 1980; today, they run about 700-750 net sf, an increase of 53%. One reason for today's bigger ORs comes from a merging of technologies: procedures that used to be conducted in multiple smaller rooms now take place in larger single rooms.

Latimer says he has heard of some ORs hitting 1,000 sf. He questions how the additional 250 sf contributes to functionality. “We're not seeing any further merging or hybridization of technologies, and there hasn't been an increase in the number of people touching the patient in the sterile zone, so there's no reason for ORs to continue to grow,” he says.

He notes, too, that ORs are also the most expensive spaces to build—often three to four times more expensive than other parts of a hospital. Latimer concedes the point that, in some instances, a larger OR may be needed to accommodate such equipment as mobile CT or MRI, laminar flow, or robotic single-plane fluoroscopes. But he says that while one or two larger ORs in a surgical floor may be acceptable, an entire floor of super-sized ORs is not.

|

| Perkins+Will’s 200-sf patient room for Salem Hospital’s North Shore Medical Center in Massachusetts meets family and caregiver needs. |

How much shell space is justified? According to Latimer, none—a very controversial zero—unless yours is one of the few hospitals that can justify the luxury of shell space. Otherwise shell space is simply not justifiable. “I think there's too much demand for space that isn't delivering any services, and the point is to eliminate everything unjustified,” he says.

His reasoning: hospitals should spend every dollar on beds they already have rather than on shell space for future beds. “Even if you know you'll need the beds in 10 years, build them in 10 years and spend the money on what you need now,” he says. At a time when most hospitals have more demands placed on them than they can afford to service, it makes no sense to spend money on shell space, says Latimer.

Latimer sees an obligation on the part of the healthcare AEC community to deliver the right-sizing message to their hospital clients—even if it's not always what the client wants to hear. “There will be a premium for architects who can deliver tight solutions that minimize size and costs,” says Latimer.

Related Stories

Digital Twin | May 24, 2021

Digital twin’s value propositions for the built environment, explained

Ernst & Young’s white paper makes its cases for the technology’s myriad benefits.

Healthcare Facilities | May 20, 2021

California Veteran Home, Skilled Nursing Facility and Memory Care project set for Yountville, Calif.

A team of Rudolph and Sletten and CannonDesign will design and build the facility.

Market Data | May 18, 2021

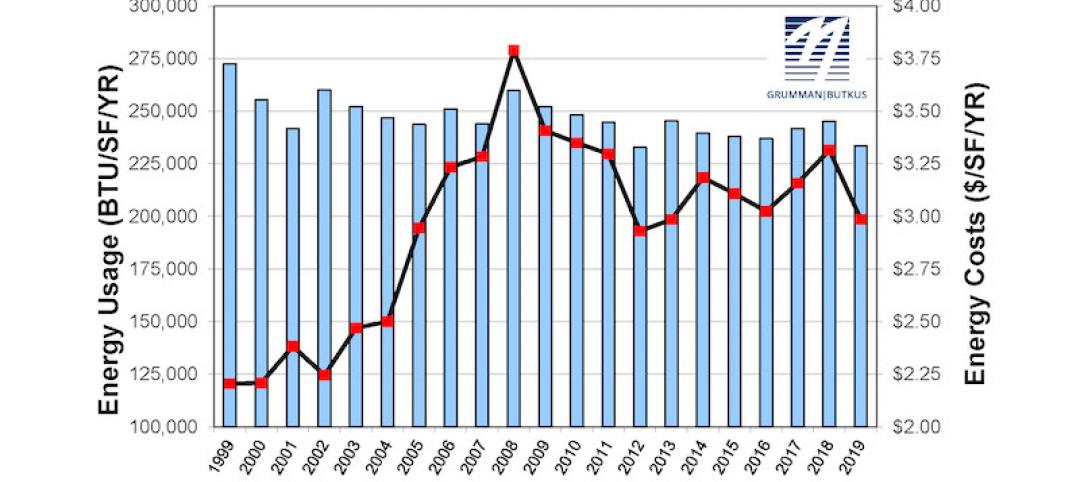

Grumman|Butkus Associates publishes 2020 edition of Hospital Benchmarking Survey

The report examines electricity, fossil fuel, water/sewer, and carbon footprint.

Healthcare Facilities | May 12, 2021

New pet ER under construction in Vancouver, Wash.

The project will serve the Portland metro area 24 hours a day.

Healthcare Facilities | May 7, 2021

Private practice: Designing healthcare spaces that promote patient privacy

If a facility violates HIPAA rules, the penalty can be costly to both their reputation and wallet, with fines up to $250,000 depending on the severity.

Healthcare Facilities | May 5, 2021

HOK to design new Waterloo Eye Institute

The project is being designed for The University of Waterloo’s School of Optometry & Vision Science.

Healthcare Facilities | May 4, 2021

New proton therapy center will serve five-state region in Midwest

NCI-designated facility an addition to the University of Kansas Health System.

Healthcare Facilities | Apr 30, 2021

Registration and waiting: Weak points and an enduring strength

Changing how patients register and wait for appointments will enhance the healthcare industry’s ability to respond to crises.

Healthcare Facilities | Apr 29, 2021

HDR selected to design new Cancer Hospital in Shaoxing

Nature is at the heart of the project’s design.

Healthcare Facilities | Apr 16, 2021

UCI Medical Center Irvine to break ground in mid-2021

Hensel Phelps + CO Architects design-build team were awarded the project.