On the surface, it may seem like we have made some pretty hefty gains from a technological standpoint in the past decade or two. It wasn’t very long ago when grabbing your laptop, opening up an app, and making a video call to someone across the world was purely science fiction.

Similarly, before this most recent decade, cell phones hadn’t quite completed their education yet that would elevate them to smartphone status. Believe it or not, the primary function of a cell phone used to be to make calls (and play the occasional game of Snake). Heck, even the Internet, one of the most important innovations ever (or was it?), is a relatively recent thing.

With amazing technology becoming such a common part of our everyday lives, it can be easy to fall into the trap of believing we are currently living in the most innovative time in human existence.

That is, until you look back at previous innovation periods a little more deeply. Take the Wright brothers and their quest for flight, for example. In 1903, on a North Carolina beach, Orville Wright piloted the first powered airplane on a 20-second, 120-foot journey; a massive accomplishment. Just 66 years later, men were setting foot on the surface of the moon. Sixty-six years—that’s all it took to go from 120 feet on a North Carolina beach to busting through the Earth’s atmosphere and traveling 230,100 miles to the moon. That smartphone in your pocket might not seem so impressive now.

And that’s just one example. As David Rotman, Editor of MIT Technology Review writes, the Internet and the personal computer are nothing compared to the dramatic decline in infant mortality, the effect indoor plumbing had on living conditions, or the invention of the light bulb or the internal-combustion engine in terms of technology generating prosperity.

The period between 1870 and 1970 was, according to Northwestern University economist Robert J. Gordon, a period of unprecedented economic growth and improvements in health and standard of living for many Americans. This century-long period is unlike anything we are ever going to see again, he argues, and the times we currently are living in certainly can’t compare.

In his book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Gordon writes that this time period between 1870 and 1970 “was unique in human history, unrepeatable because so many of its achievements could happen only once.”

The first flight of the Wright Flyer I with Orville piloting and Wilbur running alongside the airplane.

The first flight of the Wright Flyer I with Orville piloting and Wilbur running alongside the airplane.

Gordon refers to those arguing we are currently in an age of great digital innovations as "techno optimists." Gordon says not only are we not in a great age of technological and digital innovation, but we are actually experiencing a technological innovation slowdown.

Sure, we all have smartphones now and can use apps to order a car to come pick us up and take us where we want to go, order a pizza just by sending a pizza emoji (Do emoji’s count as great technological advancements?), and keep us connected with anyone in the world, but Gordon asks what this technology has done to greatly improve the way we live, such as was the case with the electric lightbulb or indoor plumbing.

The numbers seem to back Gordon up; since 2004, productivity growth in the U.S. has been glacial, and the last five years, specifically, have been close to the slowest growth ever measured. Between 1920 and 1970, American total factor productivity (a way of measuring productivity due to everything from new machines to more efficient business practices) grew by 1.89% per year. From 1970 to 1994, it only grew 0.57% each year. It experienced a boost from 1994 to 2004 as it grew at an annual rate of 1.03%, only to fall back to 0.4% from 2004 to 2014. Gordon suggests this current pace is where we are likely to stay for quite some time.

But, hold on. If there are techno optimists, is Gordon just being the antithesis of that; a techno pessimist? The innovation beginning in 1870 and continuing for a century surely didn’t come out of nowhere. It needed to be built upon other technologies and ideas. The Wright brothers didn’t just create everything out of thin air. Neither did Thomas Edison. They worked on other, smaller innovations from others that came before them. To dismiss today’s innovations and argue they do not have the possibility of leading to other, more significant innovations down the line seems like a bit of hypocritical thinking on Gordon’s part.

Every day, it seems like a new story comes out about a fascinating new piece of technology that scientists are just now scratching the surface of, but won’t be ready for practical uses for another five or 10 years. Doesn’t it follow, then, that another period of productivity, based on the technologies that are being worked on during this “slowdown,” will lead to another period of innovation?

Take another look at the numbers and you can see a pattern; periods of innovation followed by slowdowns followed by other periods of innovation. Sure, we may never have another century like the one occurring between 1870 and 1970, but as Gordon himself argues, many of those innovations were one-time discoveries. We shouldn’t fault current or future societies for the fact that past societies created something before them.

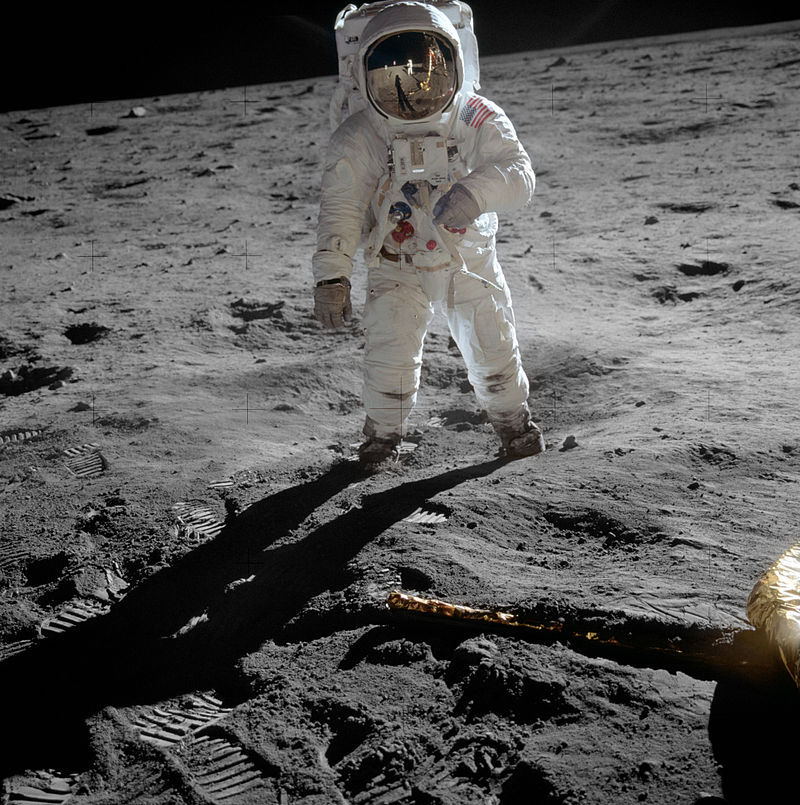

Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon in 1969. Neil Armstrong can be seen reflected in the helmet's visor.

Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon in 1969. Neil Armstrong can be seen reflected in the helmet's visor.

As Jerry Seinfeld once said, landing a man on the moon was a mistake because now everything is compared to that one accomplishment. “I can’t believe they can land a man on the moon... and taste my coffee!” he says. Gordon has a bit of this mentality (perhaps it isn’t a coincidence that we landed on the moon in 1969 and Gordon marks 1970 as the cutoff for the great age of innovation).

However, Gordon does make some good points, the main one being that innovation is bred from productivity. We cannot grow complacent and proceed with the idea that having a device that provides us with the opportunity to lob disgruntled birds at flimsy structures whenever we desire is innovation. Gordon’s argument of staying grounded and not getting swept up in the hype surrounding new iPhones and social media platforms is valuable, especially in a day and age where the world’s leading technologists are treated like rock stars.

The creation of a new technology is not the end game for innovating, it is the beginning. The next step is arguably the harder step; applying the technology to better society. It is in the application of technology where innovation resides.

To read David Rotman’s full article, click here.