The more you know about human behavior, the better you can design for it.” That’s the idea put forth by Ann Sussman and Justin B. Hollander, in their book, “Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment.”

It’s a fairly simple idea: The various tools, technologies, and spaces humans use on a daily basis should be designed for—and adapt to—us, not the other way around. Many industries recognize the benefits of this people-first approach and have sunk research dollars into trying to better understand how humans function on a daily basis.

Netflix and Hulu have dabbled in eye-tracking technology to improve their user interfaces, and Dolby Laboratories uses eye-tracking, electroencephalography (EEG), and galvanic skin response (GSR) technology to better understand how audiences respond on a neurological level to different aspects of a movie, such as specific colors and unique sounds.

The architecture industry, however, has lagged behind on this front.

![]() This illustration from eye-tracking hardware/software provider Tobii explains the basics of computer-based eye-tracking technology.

This illustration from eye-tracking hardware/software provider Tobii explains the basics of computer-based eye-tracking technology.

“Traditionally, car designers pay attention to users,” says Ming Tang, RA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C, Associate Professor at the School of Architecture and Interior Design, University of Cincinnati. “Architects focus more on the building, but we should care about the user.”

Too often, however, they don’t.

Why have architecture and design firms been so slow compared to other industries to adopt behavioral and biometric techniques to better understand how building occupants actually use buildings and spaces?

“It just isn’t a sexy kind of research,” says Chris Auffrey, Associate Professor, Bachelor of Urban Planning Coordinator, University of Cincinnati. “It is kind of like code research. It doesn’t have the appeal of actual building modeling.”

It may not be as sexy as designing a bold new addition to a city skyline, but using technologies and tactics that track how end users react to a given space can create buildings perfectly tailored to the individuals that will use them.

Current research technologies include eye tracking, which maps where and for how long users look at a given point of interest; facial expression analysis, which tracks a person’s 43 facial muscles and allows a researcher to determine a user’s emotional experience before they are aware of it; GSR, which measures electrical impulses on the hands and feet that change depending on levels of arousal or stress; and EEG, which tracks brain waves to deduce approach and avoidance responses

Tang has conducted research that combines eye-tracking tools with virtual reality technology in an effort to make signage placement and wayfinding techniques more precise, especially during emergency situations. He uses this technology combination to place people into curated virtual scenarios to deduce where they look in a given space and for how long.

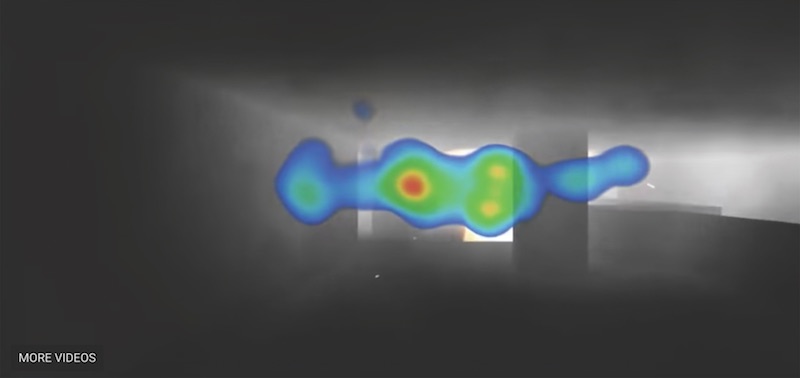

In one instance, Tang created a VR model with smoke or haze to simulate a fire emergency. The eye-tracking technology was then used to develop a heat map that showed where the individual looked—and for how long—in order to determine if the egress signage that may be effective under ordinary circumstances was still useful in emergency situations.

While there are some universals in regards to egress signage, such as illumination and the use of either green or red text, there are many variables that can determine the best position for the sign: the shape of the space, the length of the corridor, the number of people in the space at a given time, or, in this case, the intrusion of smoke. Combining the eye-tracking software with virtual reality allows for these different simulations to be run to determine the best overall sign placement for a building project.

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati have conducted studies that combine eye-tracking tools with virtual reality technology in an effort to make signage placement and wayfinding techniques more precise. Here, the team placed smoke or haze in the VR model to simulate a fire emergency and then tracked the users’ response via heat mapping of their eye movements. University of Cincinnati.

Architects must learn to kill their darlings

Some architecture firms are taking a more ethnographic observation approach to determine how people best use a given space. Certain rooms in a building may have been designed with specific purposes in mind, but if the building users are not using the space as intended, then the room is not functioning as efficiently as it should be.

The problem, according to Auffrey, is that firms don’t like to look back on their projects and realize a multi-million-dollar building might not be functioning as intended; the perfectly designed plans may not be so perfect after all.

What it boils down to is this: Are spaces functioning as intended? If not, why not? In some instances, it may be a simple scheduling or logistical issue that can be easily rectified. But in other situations, it may turn out that the architect’s great vision for how a space should be used might not fit with the end users’ reality.

Gensler, for example, partnered with Steelcase to track how often Gensler employees were using conference rooms in the company’s Houston office. Sensors were placed within the conference rooms to record when a room was occupied. It is fairly rudimentary information, but the conclusions that can be drawn from it are anything but.

![]() An example of an eye-tracking headset. Tobii.

An example of an eye-tracking headset. Tobii.

“Even at that level, it helps companies to understand whether the conference rooms are utilized as much as people claim they are,” says Dean Strombom, FAIA, LEED AP BD+C, Principal with Gensler. “We have seen a lot of research where end users will voice a concern that they can never find a conference room, only to find that typically there is a lot of open meeting space and it is really a scheduling issue more than anything else.”

On some occasions, however, a space simply may not be living up to its intended purpose. After all, life is filled with things that are good in theory but not in practice (discussing politics with family members, or anything that comes after saying, “Hold my beer”). Architecture is no different. But if architects move on to the next building as soon as the current one is built, they may propagate a flawed design approach for years.

“Unless we go back after the fact to see if spaces are being utilized, we run the risk of going on with the assumption that they are being used as designed and continue down the wrong path, only to find that what we thought was a great space that would be highly utilized, isn’t at all,” says Strombom.

Tobii technology ocmbined with a VR headset.

Tobii technology ocmbined with a VR headset.

Interpretation is everything

Data is only useful insofar as it can be interpreted, and an incorrect interpretation can be just as nocent as no interpretation at all. “One thing to be very careful about is how you interpret the data’s message,” says Tang. A heat map may show what people are looking at most, but it is up to the designers to determine if they are drawn to that spot for good or bad reasons.

There is an abundance of information that can be collected regarding how humans use a building, but the trick is to mine the data for new ways to increase employee productivity through design, according to Strombom. “There is a tendency to jump to conclusions based on some data that may or may not be accurate,” Strombom says.

One technique to get the most out of the data is to combine it with surveys of actual end users and then use the data in tandem with the survey responses to draw more accurate conclusions. But nothing is bulletproof and, unfortunately, it is a complex issue that is only growing more complex.

According to some of the tip-of-the-spear architects using biometrics and studying human behavior in relation to design, in order to simplify and solve this complex issue, more architects are going to need to shift some of their focus from the buildings they design, to the people they are designing them for.

Related Stories

| Nov 29, 2011

Turner Construction establishes partnership with Clark Builders

Partnership advances growth in the Canadian marketplace.

| Nov 29, 2011

AIA launches stalled projects database

To populate this database with both stalled projects and investors interested in financing them, the AIA in the last week initiated a communications campaign to solicit information about stalled projects around the country from its members and allied professionals.

| Nov 28, 2011

Leo A Daly and McCarthy Building complete Casino Del Sol expansion in Tucson, Ariz.

Firms partner with Pascua Yaqui Tribe to bring new $130 million Hotel, Spa & Convention Center to the Tucson, Ariz., community.

| Nov 28, 2011

Armstrong acquires Simplex Ceilings

Simplex will become part of the Armstrong Building Products division.

| Nov 28, 2011

Nauset Construction completes addition for Franciscan Hospital for Children

The $6.5 million fast-track, urban design-build projectwas completed in just over 16 months in a highly sensitive, occupied and operational medical environment.

| Nov 23, 2011

Lord, Aeck & Sargent opens fourth U.S. office, acquiring architecture firm in Austin, Texas

Strategic move offers growth opportunity and strengthens the firm’s historic preservation portfolio.

| Nov 23, 2011

Griffin Electric completes Gwinnett Tech project

Accommodating up to 3,000 students annually beginning this fall, the 78,000-sf, three-story facility consists of thirteen classrooms and twelve high-tech laboratories, in addition to several lecture halls and faculty offices.

| Nov 22, 2011

Corporate America adopting revolutionary technology

The survey also found that by 2015, the standard of square feet allocated per employee is expected to drop from 200 to estimates ranging from 50 to 100 square feet per person dependent upon the industry sector.

| Nov 22, 2011

Report finds that L.A. lags on solar energy, offers policy solutions

Despite robust training programs, L.A. lacks solar jobs; lost opportunity for workers in high-need communities.

| Nov 22, 2011

Saskatchewan's $1.24 billion carbon-capture project

The government of Saskatchewan has approved construction of the Boundary Dam Integrated Carbon Capture and Storage Demonstration Project.