As the U.S. Open Grand Slam tennis tournament in New York moves into its second week, the massive retractable roof over the 23,711-seat Arthur Ashe stadium has been drawing oohs and aahs from players and fans alike.

The $150 million roof addition is part of a $550 million renovation of the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Flushing, Queens. The roof itself was five years in the making, and posed several structural and engineering challenges to the Building Team, which included the architect Rossetti, the engineering firm WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff, and the general contractor Hunt Construction Group.

This morning, BD+C interviewed WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff execs Ahmad Rahimian, P.E., SE, F.ASCE, director of Building Structures; and Yoram Eilon, P.E., Senior Vice President of Building Structures, about this project.

Rahimian noted that any stadium construction or renovation is complicated. This one, though, was unique in several ways. For one thing, there was no precedent to draw upon in the tennis world, as Arthur Ashe is by far the largest stadium on the tour. And that facility, which opened in August 1977, wasn’t designed to include a roof.

Rahimian said that the U.S. Tennis Association (USTA), which owns and operates the venue and annual event, actually started thinking about a roof three years after the stadium opened. Those plans became more urgent in 2008, when rain interfered with the completion of some matches. Since then, rain has been a perennial threat, and occasional impediment, to the tournament’s scheduling. Design discussions for a roof began around 2011, he said.

Given the stadium’s age and structural condition, the Building Team concluded that the best solution would be to build a freestanding structure for the retractable roof that doesn’t touch the stadium itself. (There’s a 15-inch gap between the stadium and the roof pavilion.)

That roof structure sits on eight super-steel columns and 16 great brace angles that rise 125 feet above ground level, and support an 80-foot-high Teflon-covered membrane and two 500-ton panels that move back and forth over a 62,500-sf opening.

The retractable panels move on wheel assemblies mounted on rails, and can be opened or closed by cables and winches in only seven minutes.

The National Tennis Center is located in a marshy part of Queens, so the Building Team had to find answers to soil issues in order to support a roof pavilion that would weigh 6,500 tons. The steel columns are organized in an octagonal pattern that corresponds to the shape of the stadium. Each column is mounted on a concrete pier that spreads the weight load of the pavilion onto an underground concrete slab. That platform is supported by pilings that go as deeply as 180 feet into the ground.

Eilon noted, though, that this wasn’t a simple drilling job, as there are massive amounts of utilities infrastructure underground that needed to be circumvented or rerouted, not to mention the subway and Long Island Railroad systems nearby.

In addition, construction shut down during the two weeks of the tournament, which meant that cranes had to be taken down or relocated.

(Despite New York’s reputation for being a difficult place to get construction done, Rahimiam and Eilon said the city wasn’t at all intrusive. “I think they understood the significance of this to the city,” says Eilon.)

Even when the roof is open, 60% of the stadium's 23,771 seats are shaded. Image: USTA/Jennifer Pottheiser

Even when the roof is open, at least 60% of the stadium seats are shaded. To mitigate condensation and to ventilate the stadium when the roof is closed, the Building Team installed 16 air diffusers along a six-foot-wide duct that encompasses the top of the stadium, the WSP execs confirmed. As cooled air drops into the bowl of the stadium, it’s expelled by mechanical fans.

Rahimian and Eilon say that despite all this HVAC equipment, the stadium is relatively quiet when the roof is closed, although that enclosure does tends the magnify ambient sounds from the audience, which at the U.S. Open are pretty noticeable to begin with.

USTA had budgeted about $100 million for the roof project, but dealing with structural support, condensation, and ventilation tacked on another $50 million to the price tag, says Rahimian.

WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff is involved in other facets of the National Tennis Center’s renovation, which will include an expanded Grandstand stadium. Whether other sports stadiums embrace retractable roofs, though, remains to be seen. Roland Garros, the location of the French Open in Paris, intends to install a retractable roof to cover its Court Philippe Chatrier, although construction has been pushed back to 2020 at the earliest, according to Tennis Magazine.

Rahimian believes retractable roofs help venues to “justify” their brands, and he expects more projects like these in the future. “I think it’s a trend.”

Related Stories

| Jun 12, 2014

Austrian university develops 'inflatable' concrete dome method

Constructing a concrete dome is a costly process, but this may change soon. A team from the Vienna University of Technology has developed a method that allows concrete domes to form with the use of air and steel cables instead of expensive, timber supporting structures.

| Jun 11, 2014

Esri’s interactive guide to 2014 World Cup Stadiums

California-based Esri, a supplier of GIS software, created a nifty interactive map that gives viewers a satellite perspective of Brazil’s many new stadiums.

| Jun 4, 2014

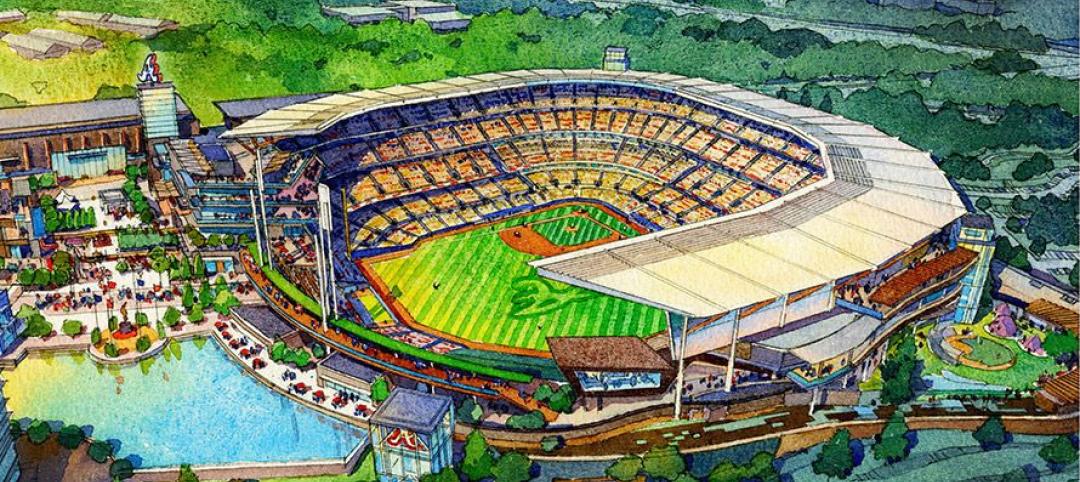

Construction team named for Atlanta Braves ballpark

A joint venture between Barton Malow, Brasfield & Gorrie, Mortenson Construction, and New South Construction will build the Atlanta Braves ballpark, which is scheduled to open in early 2017. Check out the latest renderings of the plan.

| Jun 2, 2014

Parking structures group launches LEED-type program for parking garages

The Green Parking Council, an affiliate of the International Parking Institute, has launched the Green Garage Certification program, the parking industry equivalent of LEED certification.

| May 29, 2014

7 cost-effective ways to make U.S. infrastructure more resilient

Moving critical elements to higher ground and designing for longer lifespans are just some of the ways cities and governments can make infrastructure more resilient to natural disasters and climate change, writes Richard Cavallaro, President of Skanska USA Civil.

| May 22, 2014

Just two years after opening, $60 million high school stadium will close for repairs

The 18,000-seat Eagle Stadium in Allen, Texas, opened in 2012 to much fanfare. But cracks recently began to appear throughout the structure, causing to the school district to close the facility.

| May 20, 2014

Kinetic Architecture: New book explores innovations in active façades

The book, co-authored by Arup's Russell Fortmeyer, illustrates the various ways architects, consultants, and engineers approach energy and comfort by manipulating air, water, and light through the layers of passive and active building envelope systems.

| May 19, 2014

What can architects learn from nature’s 3.8 billion years of experience?

In a new report, HOK and Biomimicry 3.8 partnered to study how lessons from the temperate broadleaf forest biome, which houses many of the world’s largest population centers, can inform the design of the built environment.

| May 16, 2014

Toyo Ito leads petition to scrap Zaha Hadid's 2020 Olympic Stadium project

Ito and other Japanese architects cite excessive costs, massive size, and the project's potentially negative impact on surrounding public spaces as reasons for nixing Hadid's plan.

| May 13, 2014

First look: Nadel's $1.5 billion Dalian, China, Sports Center

In addition to five major sports venues, the Dalian Sports Center includes a 30-story, 440-room, 5-star Kempinski full-service hotel and conference center and a 40,500-square-meter athletes’ training facility and office building.