The School of Engineering at the University of Melbourne in Australia recently announced plans to build a new campus, to open in the early 2020s, that would feature large-scale research and training facilities to test emerging technologies that address global social and environmental issues.

One of those technologies is prefabrication for construction, and the university has taken a vanguard role to push prefabrication’s market share within the country’s construction industry to 15% by 2025, from 5% currently. That increase would represent around 20,000 new jobs and 30 billion Australian dollars (US$21.1 billion) in growth.

“We are seeing huge demand in the building industry for new techniques that will allow for the development of faster and cheaper construction. The only way to reduce costs is to reduce the cost of manufacturing,” says Tuan Ngo, director of the Advanced Protective Technologies for Engineering Structures Group within the university’s Department of Infrastructure Engineering.

It's not always easy to pinpoint a movement's breakthrough moments. But an online article that Deloitte posted on February 26 makes the case for a high-rise project in Melbourne, completed in 2010, that deployed a construction technique where entire floors of the building were completed offsite and assembled onsite by snapping together the modules one on top of the other.

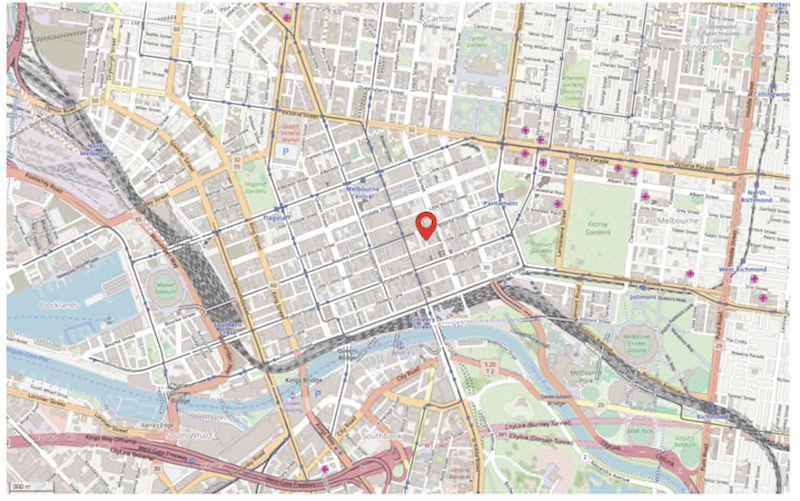

The location: Russell Place in Melbourne’s central business district. That real estate was problematic to build on because it sat over one of the district’s electrical substations. Weight restrictions limited the mass of any building constructed on the site, and ground vibration had to be minimized.

The land owner, a pre-eminent architect named Nonda Katsalidis, circumvented these roadblocks and restrictions by treating the construction process as a design-for-manufacture-and-assembly problem, rather than a building problem.

Russell Place, where the Little Hero building was assembled, sat over a primary electrical substation for Melbourne's central business district, which presented several construction limitations. Image: Deloitte Insights

Katsalidis’ twist on an already-established design-for-manufacturing technique was to “unitize” the building, so that each unit—in this case, each floor—was finished in a factory and then transported completed to the jobsite for quicker assembly, a la LEGO Duplo.

Executing this approach required making a digital model of the entire building, accurate to its light fittings, power sockets, washers, and door hinges. Deloitte’s authors called this BIM on steroids.

To pull this off, Katsalidis cofounded a technology company, Unitised Building in 2008, and partnered with a building firm Hickory Group to create the tooling required, and to develop and manipulate the models.

The Russell Place site was the first to host a building constructed with Unitised Building’s modular method. Completed in 2010, the building, called Little Hero, contains 63 one- and two-bedroom apartments and duplex penthouse residences, all of which sit atop seven retail shops, cafés, and restaurants. The unitized process not only complied with all of the site’s restrictions, but cut construction time by more than six months compared to a conventional approach: The eight-story building took only four weeks to erect, at a cost comparable to that of a conventional process.

Deloitte’s authors explain that what separated the unitized approach from conventional prefab modular design and construction at that time was that it was easier to customize, focused on mid- to high-rise construction, and allowed completed modules to be “snapped” together, in contrast to a kit of parts approach.

In addition, say the authors, unitization offered a new way to export BIM data. “It is possible for a firm to retain possession of the models and export only the instructions they generate, to guide the machines and workers in a remote contract manufacturing facility and the remote building site. The models are held domestically, where the engineering talent required to develop and maintain the IP in them is located.”

Deloitte’s authors note that unitization has since led to a larger discussion about different approaches to building as an activity. Rather than simply digitizing existing building practices … “we need to digitalize building by shifting the foundation of our operating model to a wholly different premise,” they wrote.

The unitized process sometimes requires improvisation, too. In 2017, Hickory Group was working on a site within Melbourne’s central business district where access was awkward. The crane that was needed to lift building units into place blocked a narrow laneway, making it difficult for local residents to access their properties.

To navigate the problem, the firm offered to build only at night. To prove this approach to skeptical a city council and residents, Hickory ran a trial build one night, which went unnoticed despite the firm warning nearby residents about it beforehand. With the council and residents convinced that installing building units at night would work, construction went ahead.

King 25, Australia's tallest timber building, was assembled using prefabricated engineered wood components. Image: Wonderful Engineering

Whatever success Unitised Building and other companies may have had, it remains to be seen whether prefab construction can get beyond the nascent stage in Australia.

Prefab, as a concept, got a boost when Australia’s tallest timber building, the 10-story 45-meter-tall (148-ft-tall) 25 King, an office and residential tower in Brisbane, opened earlier this month. Designed by the architectural firm Bates Smart, the building’s engineered-wood components were prefabricated offsite. The entire construction took 15 months to complete.

But supply and demand are still in question. One one hand, Strongbuild, which made prefab houses from an 8,000-sm (86,111-sf) factory in Sydney, last November lost a AUD$45 million contract and went into voluntary “administration,” Australia’s version of liquidation.

On the other hand, David Chandler, a former builder who is now adjunct professor in construction management at Western Sydney University, told the Australian Financial Review that the country could lose up to 200,000 construction jobs to offshore competition if it doesn’t set up a viable prefab construction industry within the next decade.

Related Stories

| Apr 8, 2013

Most daylight harvesting schemes fall short of performance goals, says study

Analysis of daylighting control systems in 20 office and public spaces shows that while the automatic daylighting harvesting schemes are helping to reduce lighting energy, most are not achieving optimal performance, according to a new study by the Energy Center of Wisconsin.

| Apr 5, 2013

'My BIM journey' – 6 lessons from a BIM/VDC expert

Gensler's Jared Krieger offers important tips and advice for managing complex BIM/VDC-driven projects.

| Apr 3, 2013

5 award-winning modular buildings

The Modular Building Institute recently revealed the winners of its annual Awards of Distinction contest. There were 42 winners in all across six categories. Here are five projects that caught our eye.

| Mar 27, 2013

Small but mighty: Berkeley public library’s net-zero gem

The Building Team for Berkeley, Calif.’s new 9,500-sf West Branch library aims to achieve net-zero—and possibly net-positive—energy performance with the help of clever passive design techniques.

| Mar 26, 2013

Will Google Glass revolutionize the construction process?

An Australian architect is exploring the benefits of augmented reality in the design and construction process.

| Mar 24, 2013

World's tallest data center opens in New York

Sabey Data Center Properties last week celebrated the completion of the first phase of an adaptive reuse project that will transform the 32-story Verizon Building in Manhattan into a data center facility. When the project is completed, it will be the world's tallest data center.

| Mar 20, 2013

Folding glass walls revitalize student center

Single-glazed storefronts in the student center at California’s West Valley College were replaced with aluminum-framed, thermally broken windows from NanaWall in a bronze finish that emulates the look of the original building.

| Mar 13, 2013

Replacement escalators give Cobo Center a lift

New elevator technology enables Detroit’s Cobo Center to replace its escalators without disruption to its convention business.