The adoption of BIM has had a clear impact on the building industry’s processes for designing and delivering buildings. The benefits can be seen through numerous reports showing that 75% of projects invested in BIM realized a positive return on investment and that BIM can even save an owner in construction costs of up to 45%. However, it appears to us that owners have yet to see benefits from one major facet of BIM: data.

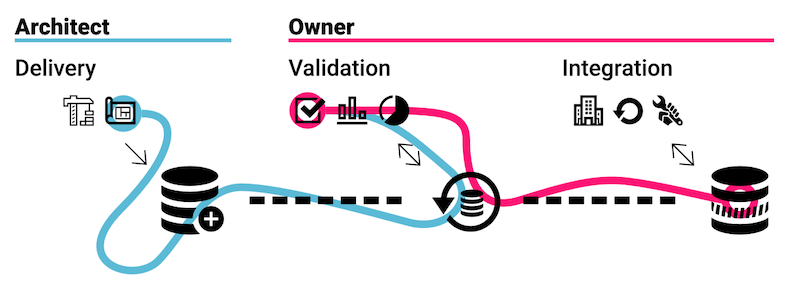

A well designed, coordinated, and constructed building fits nicely in preparing an owner for operational success once the keys are handed over. We’ve noticed that owners are increasingly asking architects to furnish them with the project-related BIM deliverables leveraged during the design and construction of their facilities. But a major aspect of a model’s potential value frequently slips down the drain when the model is not situated for use by an owner – or the owner isn’t equipped to leverage the deliverable in the long-term. Often, these models just sit on some sort of a digital “shelf” poised to collect dust.

In recent years, we have found our consulting practice engaging more and more with owners that are questioning the value of BIM and how they can make use of potentially data-rich BIM assets. In several recurring engagements, we are working with owners to integrate data and make data-driven business decisions more accessible. We’re fortunate to be working with a number of owners who are tackling their own unique issues that relate to this. Here are 4 takeaways for what we are seeing in our work:

1. Same tools, different uses

Recently, we took a deep dive into an owner’s Revit models of some recent major building projects in an attempt to find potential connections between room object parameters and an owner’s long-standing operations and maintenance platform. It didn’t take long to find, in the models authored by the design and construction teams contained inconsistent room names across similar use types, even in the same project.

While BIM authoring tools, such as Revit, provide common data structures, the data values themselves are often produced through a combination of manual data entry, inconsistently applied standards, and bespoke automation routines. While humans can interpret room names like “Custodial” and “Janitor” as similar spaces, an application or database cannot without manual intervention or anticipation of numerous edge cases making out-of-the-box utilization of this architect’s model difficult.

BIM content, such as equipment and furniture, is another area where we observe numerous challenges. One owner indicated the need to make use of BIM to track important equipment in parallel with maintenance systems. We we cracked open a few of their models we found that only 40% of an architect’s BIM submittal followed an owner’s defined naming conventions provided for parts and fixtures.

Content was sourced from multiple locations or created from scratch. As a result, digital content present in the model was not easily reconciled with an understanding of their physical counterparts. It was identified that a core issues in the process was accountability for the digital deliverable: The challenge this owner faced was finding ways to ensure architect’s compliance of standards that were already in place.

2. Expectations need to catch up

We’ve also observed owners approaching incoming BIM data from architects using old tools and methods. In several cases where the architects handed over 3D models at the end of a project, the owner was primarily leveraging 2D information and manual re-drawing processes to validate object geometry before utilizing it within internal systems. In fact, the systems they were integrating with had few options for automating the integration of BIM geometry. This represents two common roadblocks: 1. familiar processes were favored over implementing new ones and 2. common facilities management software possess inadequate tools for consuming and leveraging BIM data.

In another instance, an owner with more technical-savvy resources opted to reverse-engineer a complicated data processes in an effort to expose additional data points from pre-existing proprietary tools – forgoing adopting newer platforms that promised easier use. In this case, the process was clearly being subjected to the sunk cost fallacy wherein effort to expand on the functionality from major prior investments in closed or archaic systems overshadowed newer, simpler, more open processes and opportunities.

3. Even the experts have skills gaps

Several of our clients retain permanent data analysis personnel to support continued implementations and integrations of their systems. These staff often possess deep experience in relational databases and likely see the world through SQL joins and subqueries. Challenges arise when robust data expectations and building information models collide. While integrating BIM data with other systems, like procurement and sales is ripe with possibilities, it takes time and effort to understand the paradigm of 3D asset representation and the surrounding schema that we utilize today.

In one particular instance, we observed a data expert was designing an analysis schema to connect BIM data to other internal systems. Here a significant skills gap emerged: a lack of familiarity with 3D BIM processes and data structures resulted in a challenges in mapping the data to their required systems. When combined with point 1 and 2 above, we found some that significant skills uplift was necessary in their understanding of how physical assets were represented in the resultant relational data that was exported from the BIM platform they were using. While we aren’t advocates of data analysts moving walls and clouding revisions in documents, we do see a direct benefit when BIM platform learning and increased familiarity is fostered across internal disciplines.

4. What do you want out of this?

If we understand BIM is philosophically the organization of 3D and data to design a digital representation of a building, the major benefit for owners to having access to these assets is the ability to leverage data for the end uses and operations of a facility. In order for those documents to be usable, we believe an owner must provide robust expectations and processes for accountability for a project team to satisfy those needs. Here’s a great first step: understand what data derived from building information models can be integrated into your business platforms and work backwards from there.

In our experience with one owner, we worked with them to get a sense of how their trusted architects and contractors would respond to more robust data requirements for their digital deliverables. After some targeted discussion with multiple groups, we found a varying and inconsistent level of importance given by design and construction team partners to owner-specified standards and requirements. This suggested to us that, while architects and contractors have been utilizing BIM for the benefit of projects, reasserting the impact and value that data has for owners is of prime importance. Even after 15 years of industry adoption of Revit – North America’s primary BIM authoring tool – the reliability and value of owner-centric BIM uses is still new territory for many.

If you’re an owner trying to tackle these types of initiatives, it might be relieving that others are experiencing similar issues. These growing pains are indicative of a worthwhile future state where clear pathways of utilizing data from architects and contractors produce benefits for business analysis, facility operations, and future design. While an architect and contractor may see BIM workflows solely as benefitting the delivery of a physical solution, the inherent data and its value to an owner must not be discarded. Importing data about their new facility born during design and grown through construction takes away the mountainous burden of originating that data themselves once an owner occupies the building.

Careful consideration needs to be taken in order to ensure robust data deliverables are provided by architects and contractors to an owner. As an owner, what standards documentation or contract considerations have you taken to get what you need from your project teams? As an architect or contractor, how have you ensured the data in your digital deliverable is worthwhile to your owner’s specific needs?

More from Author

Proving Ground | Apr 14, 2021

Business intelligence: 5 drivers for adoption in architecture and construction

This article will explore some of the drivers for how BI is finding successful adoption among architects, engineers, contractors, and owners.

Proving Ground | Mar 24, 2019

5 ways designers and builders can use business intelligence with data they already have

Tricky construction budgets, large project teams, and unique designs needing extensive coordination are all problems increasingly being handled with new software tools and data.

Proving Ground | Aug 21, 2018

Five habits that are keeping your digital strategy from working

Strategies are always created with the best of intentions for improving business, the effort involved in executing the strategy – especially ones involving disruptive digital capabilities – is greatly underestimated.

Proving Ground | Dec 12, 2017

Reflecting on the future of work

'I believe in the potential for new technology to positively impact the quality of the built environment with immense speed and great efficiency,' writes Proving Ground's Nathan Miller.

Proving Ground | Oct 6, 2017

How professional bias can sabotage industry transformation

Professional bias can take the form of change-resistant thinking that can keep transformational or innovative ambitions at bay. Tech consultant Nate Miller presents three kinds of bias that often emerge when a professional is confronted with new technology.

Proving Ground | May 24, 2017

Data literacy: Your data-driven advantage starts with your people

All too often, the narrative of what it takes to be ‘data-driven’ focuses on methods for collecting, synthesizing, and visualizing data.

Proving Ground | Feb 16, 2017

Positioning computational designers in your business: 4 things to consider

There appears to be very little industry consensus as to what a ‘computational design’ position actually means in a business setting.

Proving Ground | May 9, 2016

3 things to consider for computation in the business of design

In creating a roadmap for computation, Proving Ground's Nathan Miller likes to consider investing in the right people, incorporating a range of skillsets, and defining the business value.

Proving Ground | Apr 15, 2016

Should architects learn to code?

Even if learning to code does not personally interest you, the growing demand for having these capabilities in an architectural business cannot be overlooked, writes computational design expert Nathan Miller.