100-year flood. 500-year flood. These are the curious and somewhat misleading terms that meteorologists, emergency response organizations, and resiliency planners use to discuss flood events. A 100-year flood is one that reaches a level that, statistically speaking, stands a good chance of occurring once in a hundred years. Likewise, a 500-year flood might occur once every 500 years. However, this is not a schedule; It’s merely a statistic based on historical data and future projections. It’s useful for planning for the “worst-case scenario”, but it is important to remember that major floods can happen at any time. Optimistically, a city might go three or four centuries without hitting 100-year flood levels. On the other end of the spectrum? Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Cedar Rapids, a city of 130,000, had only eight years between their first and second highest floods on historical record. First was the 2008 flood. Exceeding the 500-year flood level (that is, a flood that has only a .2% chance of occurring in any given year), the water crested at 31 feet above the riverbank. Emergency evacuation protocols and sufficient warning prevented any loss of life, but the impact shows in terms of displacement and dollars: 10 square miles of the city were flooded, some 24,000 residents were evacuated; damage to 7,000 affected properties tallied up to $6 billion. The impact of the more recent flood—this September—was considerably less. This is due both to the lower flood level (the water still crested at 22 feet, making it the second highest on record) and the fact that the city was more prepared this time—largely due to a river corridor plan developed by Sasaki and the City.

Writing for Landscape Architecture Magazine (LAM), reporter Zach Mortice tells the tale of the city, its floods, and the years in between in “Cedar Rapids, Readier for this Flood.” He interviewed Sasaki Principals Gina Ford, ASLA, and Jason Hellendrung, ASLA, on work that the firm has done for Cedar Rapids. Ford and Hellendrung, as Mortice relates, have a unique connection to the city and its challenges. Having traveled to Cedar Rapids on June 11, 2008 for a greenway master plan kick-off, they awoke the next morning to experience the impact of the flood firsthand. The flood would rise higher through the 12th, before finally cresting on the 13th.

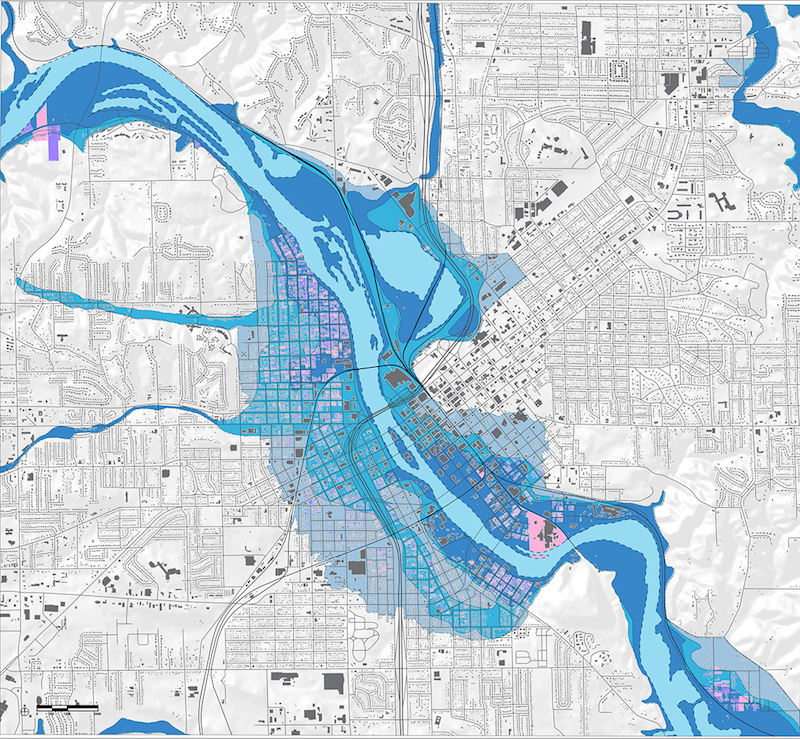

A flood plain map of Cedar Rapids shows the 100-year level in dark blue, 500-year level in lighter blue, and the extent of the 2008 flood in gray-blue.

A flood plain map of Cedar Rapids shows the 100-year level in dark blue, 500-year level in lighter blue, and the extent of the 2008 flood in gray-blue.

The Day After

You can read the full story of those surreal days in the field on LAM—but it is no exaggeration to say that this flood would prove to be a defining moment of the project. It not only brought Ford and Hellendrung closer to the community’s experience, but refocused the entire purpose of the master plan. What was originally intended as a reinvigoration of the riverfront and city core quickly shifted to incorporating protection against future floods. Community outreach was critical and irrepressible to developing the plan—the community truly bonded together to share thoughts on how best to rebuild after this disaster. One of the most pressing questions moving forward centered on how to treat properties that had flooded.

“What made this effort so successful was how engaged the community was from day one,” says Hellendrung. “Together, we developed several strategies against future floods as well as plans to reinvigorate the city. Options varied from walling off the river entirely to buying out the 7,000 properties that had flooded. Through working with the community, we landed in the middle—leading to the development of the greenway and a vibrant Riverwalk in the downtown that could be protected with demountable flood walls.”

The Years After

The purchase of 1,300 parcels paired with city-owned property enabled the creation of a 220-acre greenway. Today, the sloping, lush greenway is a place for circulation, play, and programming in good weather, but serves as a levee in floods—a buffer between the river and the city. Along the west bank of the river is the popular McGrath Amphitheatre, which hosts several major concerts and events throughout the year—successfully activating the riverfront. The amphitheatre, completed in 2014, and the greenway illustrate another central goal of our work in Cedar Rapids: designing double-duty infrastructure:

“Traditional flood prevention strategies often call for building tall flood walls along the riverbank,” says Ford. “While this is an effective strategy, it cuts communities off from their river—a great resource for recreation and natural beauty. In Cedar Rapids, we flipped the traditional treatment on its head. More than 99% of the time, the river isn’t flooded, so the question became ‘how can we design great public places that also offer proficient flood protection?’”

The popular McGrath Amphitheatre doubles as a levee during flood events.

The popular McGrath Amphitheatre doubles as a levee during flood events.

Beyond Resilience: Revitalization

The pre-flood impetus for the plan was to reinvigorate the riverfront and its connection with adjacent neighborhoods. “The Cedar River is an amenity that serves to enhance the quality of life attraction for the City,” says the original request for qualifications, “and its plans are to rival any of the greatest river towns in America.” Though the 2008 flood changed the conversation in many ways, the city and community was still committed to celebrating the recreational and social value the river offers.

The greenway celebrates the city’s connection with the riverfront.

The greenway celebrates the city’s connection with the riverfront.

It’s a smart investment, and Cedar Rapids is in good company. Cities across the country have begun viewing their river and waterfronts—which have all too often languished as post-industrial dead zones—as major opportunities for revitalization. Investing in riverfront recreation is a proven economic generator for cities. A study we recently completed for Riverlife, a Pittsburgh riverfront advocacy group, draws a dramatic correlation. The study connects the city’s $130 million in riverfront investments to over $4.1 billion in development and soaring property values.

A 2013 study by the Friends of the Chicago River show that each dollar invested in the Chicago River “provides a 70% return through business revenue, tax revenue, and income while creating 52,000 construction jobs and 846 permanent operations and maintenance jobs.” The Chicago Riverwalk, which celebrated the opening of its final phase last week, is palpable proof of the activation power riverfront design offers. Blair Kamin, architecture critic for the Chicago Tribune, described the project as a “path that will stretch uninterrupted for 1 and ¼ miles and will have transformed harsh industrial-era docks into a teeming postindustrial amenity” in a recent review.

We are humbled to have worked with such a strong community as Cedar Rapids. Together, we created a plan that invests not just in recreation space, not just in flood protection—but in both. That approach is reinvigorating the city’s vibrancy and has become a successful case study for planning for the worst while raising the quality of life to their best levels yet for the people of Cedar Rapids.

More from Author

Sasaki | Feb 5, 2024

Lessons learned from 70 years of building cities

As Sasaki looks back on 70 years of practice, we’re also looking to the future of cities. While we can’t predict what will be, we do know the needs of cities are as diverse as their scale, climate, economy, governance, and culture.

Sasaki | Aug 6, 2021

Microclimates and community

Creating meaningful places that contribute to a network of campus open spaces is a primary objective when we design projects for higher education.

Sasaki | Apr 12, 2021

I’ll meet you right outside: Microclimates and community

These high quality exterior gathering places are increasingly important in supporting community.

Sasaki | Feb 16, 2021

A humanistic approach to data and design in the COVID era

As the COVID crisis continues to disrupt higher education, Sasaki is working with our campus clients on space planning initiatives that harness data to uncover solutions to complex challenges never before faced by college and university leaders.

Sasaki | Jul 28, 2020

Post-pandemic workplace design will not be the same for all

Regardless of whether it takes 3 or 18 months to fully return to work, it is clear the long march toward re-emergence from this global pandemic will likely be more of a gradual re-opening than a simultaneous return to life as we knew it.

Sasaki | May 31, 2018

Denver's airport city

Cultivation of airport cities is an emerging development strategy shaped by urban planners, civic leaders, airport executives, and academics.

Sasaki | Feb 12, 2018

Stormwater as an asset on urban campuses

While there is no single silver bullet to reverse the effects of climate change, designers can help to plan ahead for handling more water in our cities by working with private and public land-holders who promote more sustainable design and development.

Sasaki | May 26, 2017

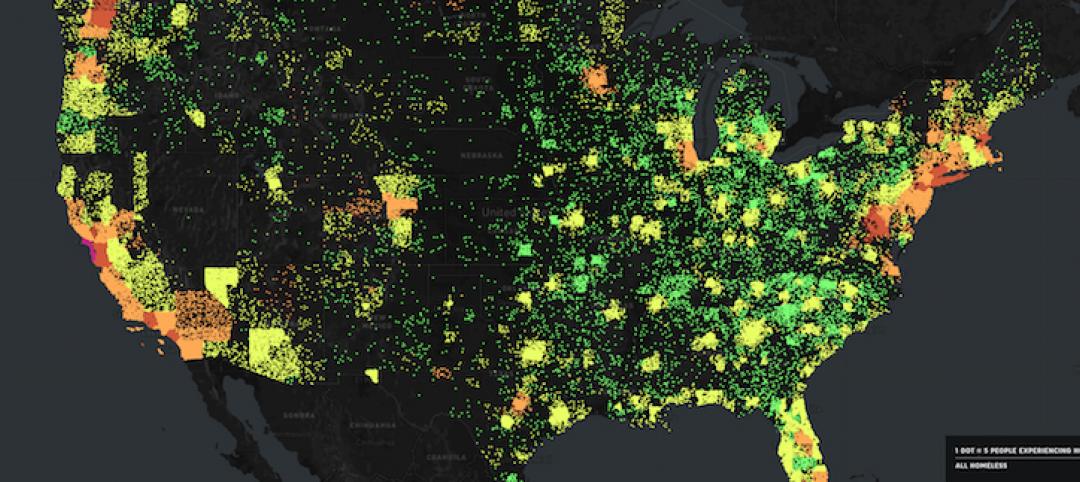

Innovations in addressing homelessness

Parks departments and designers find new approaches to ameliorate homelessness.

Sasaki | Apr 3, 2017

Capturing the waterfront draw

People seem to experience a gravitation toward the water’s edge acutely and we traverse concrete and asphalt just to gaze out over an open expanse or to dip our toes in the blue stuff.

Sasaki | Dec 14, 2016

The future of libraries

The arrival of programs that support student and faculty success such as math emporiums, writing centers, academic enrichment programs, and excellence-in-teaching centers within the library, heralds the emergence of the third generation of academic library design.