Nearly 32 million people, or 28% of the East Coast's population, live in areas lying within a mile of a shore line. These are huge swaths of land inhabited by large populations—and these communities are at distinct risk of devastation given the trajectory of rising sea levels and the growing frequency and strength of major storms.

Coastal communities along the eastern seaboard were not always in such danger. Early settlers built their towns along protected waterways rather than directly on ocean shores to insulate themselves from threats. While this initial planning proved sound, over time cities filled in land to continue expanding, making some of the East Coast's largest cities the most at-risk, including Boston, New Haven, Washington DC, and New York City.

The good news is that these municipalities are paying attention. Better yet, the federal government is invested in finding a safe path forward for regions at risk nationwide. Obama's administration earmarked $1B toward an innovation and design competition inviting communities recently affected by natural disasters to compete for funds to both rebuild and bolster resilience in anticipation of future incidents.

Borrowing from the successful model of HUD's Rebuild by Design competition, the goal of the National Disaster Resilience Competition is to "get resources to communities to help them develop innovative, data-driven, and community-led approaches to recover from their disasters and increase resilience to future threats." HUD hopes for widespread participation from regions across the U.S and will post the Notice of Funding Availability in the coming weeks to officially solicit proposals.

In light of the new funds available it is the prime opportunity to think hard about the kinds of interventions shorefront communities can make to rebuild with an eye toward the future. It requires an acceptance of the new threats these communities face and a willingness to think about coastal resilience differently. Sasaki has developed several innovative solutions with input from the public and civic leaders in the wake of Hurricane Sandy and can help similar coastal communities begin to think about what a path forward could look like:

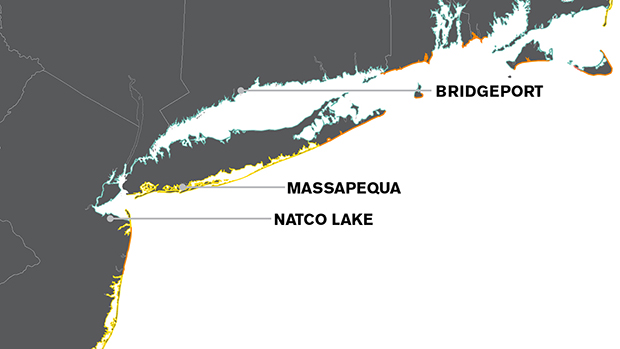

• Massapequa, N.Y. Following Hurricane Sandy, Massapequa and Massapequa Park, faced flooding, unlit streets, and infrastructure failure. It was clear that to rebuild Massapequa needed to construct a lifeline road network with key segments elevated to prevent flooding. Green infrastructure systems were also integral to several proposed projects to make Massapequa more resilient; these systems range from restored shorelines to flood valves to storm-absorbing park design.

• Natco Lake district, N.J. The Natco Lake district is a complex shoreline region encompassing Union Beach, Keansurg, and a manmade lake between them. This rich estuarine environment supports densely-populated maritime communities, a variety of industrial uses, and a local economy increasingly tied to New York City. In rebuilding the objective was to reduce flooding from storm events, protect communities from storm surge risks, and reconnect residents and visitors to a regional recreation amenity that provides better drainage into watersheds and wetlands.

Achieving this objective would require developing marsh landscapes to mitigate contamination and support fishing in the area; cleaning creek watershed through dredging; removing non-native vegetation to accommodate more wetland surface area to absorb flood water from neighboring towns; and linking the community to these recreational sites with trails so that the Natco Lake district transforms into a community destination.

• Bridgeport, Conn. Parks will become the green infrastructure of Bridgeport, supporting the ecological, social, and economic health of the city. The linear waterfronts are an important part of the park system as a network of public access along all creeks within Bridgeport's boundaries. The parks and waterfront will play an important role in improving the ecological health and diversity in this city. Over the next decades, Bridgeport's restoration of the shoreline will prevent erosion, protect key habitat areas, absorb stormwater, and brace for storm surges.

If you live on the East Coast there is a 1 in 3 chance that you live within a mile of the shoreline. In fact, 51% of the total length of the East Coast, over 2,000 miles, exist in similar conditions to those described in Massapequa, Natco Lake district, and Bridgeport. The funds, the support, the expertise, the community engagement, the framework, and the sheer momentum, are all there to support municipalities on the east coast and across the country to rebuild for the future.

And these particular examples, culled from the NY Rising competition, provide good models for how to engage in a top-town and bottom-up approach to incorporate both the needs of the community and industry expertise to find resiliency solutions that can actually leave the drawing board and get implemented. It is absolutely the right time to make meaningful investments in the areas facing the greatest risk.

As former Mayor Bloomberg so eloquently expressed, "let me be clear: We are not going to abandon the waterfront. We are not going to leave the Rockaways or Coney Island or Staten Island's South Shore. But we can't just rebuild what was there and hope for the best. We have to build smarter and stronger and more sustainably." That is the charge, not just for New York but for all the regions lining the Atlantic coast that remain vulnerable to natural threats today and are ready to solve for ways to take those threats head-on.

Read on about innovative approaches to engaging communities and tapping into the best and brightest in academia and beyond within the NY Rising competition.

Read more posts from the Sasaki Ideas blog

More from Author

Sasaki | Feb 5, 2024

Lessons learned from 70 years of building cities

As Sasaki looks back on 70 years of practice, we’re also looking to the future of cities. While we can’t predict what will be, we do know the needs of cities are as diverse as their scale, climate, economy, governance, and culture.

Sasaki | Aug 6, 2021

Microclimates and community

Creating meaningful places that contribute to a network of campus open spaces is a primary objective when we design projects for higher education.

Sasaki | Apr 12, 2021

I’ll meet you right outside: Microclimates and community

These high quality exterior gathering places are increasingly important in supporting community.

Sasaki | Feb 16, 2021

A humanistic approach to data and design in the COVID era

As the COVID crisis continues to disrupt higher education, Sasaki is working with our campus clients on space planning initiatives that harness data to uncover solutions to complex challenges never before faced by college and university leaders.

Sasaki | Jul 28, 2020

Post-pandemic workplace design will not be the same for all

Regardless of whether it takes 3 or 18 months to fully return to work, it is clear the long march toward re-emergence from this global pandemic will likely be more of a gradual re-opening than a simultaneous return to life as we knew it.

Sasaki | May 31, 2018

Denver's airport city

Cultivation of airport cities is an emerging development strategy shaped by urban planners, civic leaders, airport executives, and academics.

Sasaki | Feb 12, 2018

Stormwater as an asset on urban campuses

While there is no single silver bullet to reverse the effects of climate change, designers can help to plan ahead for handling more water in our cities by working with private and public land-holders who promote more sustainable design and development.

Sasaki | May 26, 2017

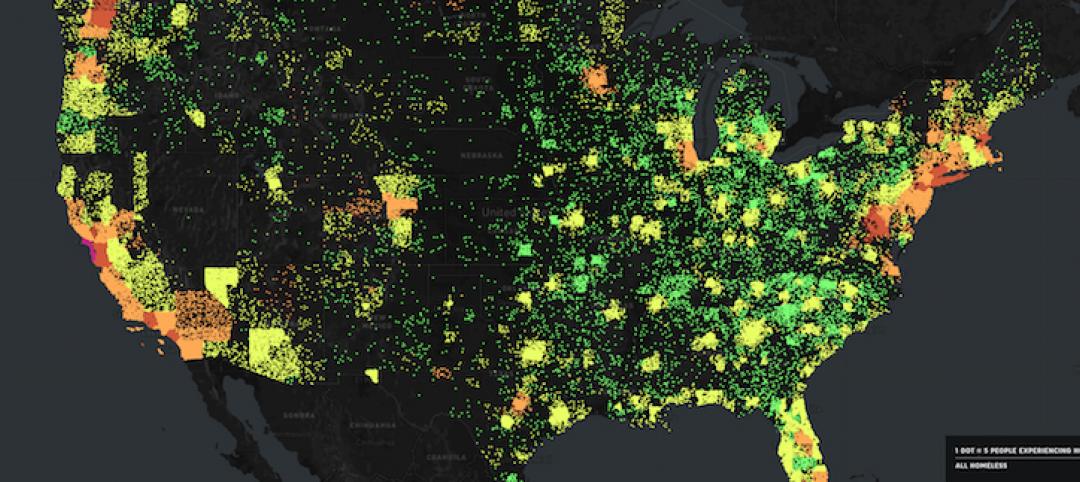

Innovations in addressing homelessness

Parks departments and designers find new approaches to ameliorate homelessness.

Sasaki | Apr 3, 2017

Capturing the waterfront draw

People seem to experience a gravitation toward the water’s edge acutely and we traverse concrete and asphalt just to gaze out over an open expanse or to dip our toes in the blue stuff.

Sasaki | Dec 14, 2016

The future of libraries

The arrival of programs that support student and faculty success such as math emporiums, writing centers, academic enrichment programs, and excellence-in-teaching centers within the library, heralds the emergence of the third generation of academic library design.