As a firm tasked with designing the buildings and cities that shape our future, we are challenging ourselves to imagine a new way of developing places. One where nature is the city, and the city is treated as a natural system.

For much of the past 100 years, designers and planners have worked around automobiles as the main organizing mechanism for cities. And in order to accommodate cars—both how they move and how they’re parked—20th century planners had to develop an elaborate system of roadways that became largely divorced from greenspace.

Whether it happens in the next decade or beyond, the North Star of nature as the city now guides our practice. And this approach helps to move toward the world we want to see—where our cities are greener and more habitable, for all people who live and work in them.

The reasons to use nature as the guiding principle are myriad. At an individual level, we know that access to greenspace makes us healthier, less depressed and anxious, more connected and more creative (and we also know that for too many in our cities, there is little to no greenspace access). In her book The Nature Fix, writer Florence Williams outlines the ‘nature pyramid,’ a concept that says we need ‘differing frequency, duration and intensity of immersion’ in nature in order to be well. While big, awe-inducing experiences in nature—like those found at national parks—are something to visit on occasion, it’s our daily experiences in cities that make up the bulk of our exposure.

At a systems level, green infrastructure—in the form of public parks, wetlands and grasslands, urban forests, green roofs and siding, and rainwater gardens—is our most affordable and most effective technology in protecting cities from the impacts of climate change. This green infrastructure makes our cities more beautiful and more livable and serves a critical function in stormwater management, reducing pollution, and decreasing the urban heat island effect.

By treating the city as a natural environment, we have the opportunity to soften its hardness, both literally and figuratively. Here are five ideas we’re both inspired by and actively integrating into our projects to ensure more healthy, natural cities:

City and District-Wide ‘Sponge City’ Solutions

Across Asia, most notably in Hong Kong and Southern China, cities are now five years into an experiment in investing in landscape and green infrastructure to counteract the region’s hyper-urbanization. The ‘Sponge City’ model looks to simultaneously address issues of flooding, water shortages and water pollution, turning entire districts and cities into landscape sponges to capture and retain stormwater and preserve it for future use. For Tencent’s 22-million square foot Shenzhen Headquarters Project Master Plan, a series of green pathways and corridors, open public greenspace, mangrove plantings along the district’s waterfront, and wetlands are integrated throughout the multi-acre project.

The Growth of Landscape Infrastructure in North America

In the US, ambitious rails to trails projects like the Nickel Plate Trail outside Indianapolis, Rail Park in Philadelphia and infrastructure endeavors like the LA River initiative are a ubiquitous approach to multipurpose infrastructure creating adapted greenspace, restoring habit, climate control measures and introducing new opportunities for transport and recreation.

Street Level Greenscape Interventions

Innovative approaches to leveraging the power of natural interventions can also be found at the individual street level.

In Seattle, the city is implementing a series of bioswale streets, using native plantings to create natural drainage systems while also turning sidewalks and roadway medians from places you’d never notice into beautiful settings. For example, a cascading rain garden under a major bridge in the city’s Fremont neighborhood now gathers and filters 200,000 gallons of stormwater annually.

In Boston, we’re working with the neighborhoods of Allston and Brighton to preserve and expand the local tree canopy in the midst of a wave of new development. A key approach is to strategically identify sidewalk greening opportunities pair them with a planting guide.

These seemingly simple interventions can be some of the most valuable and effective microscale solutions, yet also can be the most challenging to retrofit into neighborhoods that most need it.

The Introduction of New Habitat and Wildlife Corridors

Cities including Portland and Oslo are exploring butterfly and bee highways and urban wildlife corridors to create safe habitat for birds, animals and other wildlife. These habitat interventions need to be connected across scale to be successful. This is why even smaller projects have an important role to play. For example, at the Gahanna branch location of Columbus Metropolitan Library in Columbus, Ohio, a butterfly garden at the perimeter of the building is being designed.

Commercial Buildings, Campuses and Utilities Greening Our Cities.

While a host of forward-thinking companies including Samsung and Vivo understood the benefits of indoor-outdoor work prior to the pandemic, the integration of green roofs, patios and balconies with plantings and multipurpose outdoor settings are now critical to the future of the office. In fact, companies increasingly view it as their responsibility to create these kind of environments, both for the health and well-being of their employees and for their communities. We’re also starting to see what it can look like to integrate greenspace with public utilities, as Seattle City Light does with the Denny Substation. The project brings together greenspace and a dog park on the same site as the city’s newest electrical substation.

And at a campus level, bringing in new natural design elements can support citywide green infrastructure goals. For Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, the transformation of Nash Walkway with the introduction of new plantings and an outdoor study garden creates a more nurturing environment for students and staff and supports local habitat restoration.

Moving Toward a More Coherent Approach to Nature as the City

These individual efforts are remarkable—but if we want the city to become an interconnected, natural ecosystem, we need to find more overarching ways to stitch them together. And we need to continuously explore ways to look for lessons from the biomes themselves. The architecture of nature itself has a lot to teach us about energy production and water reuse and percolation.

We already see some cities take the lead on more comprehensive commitments to green master planning. London is making moves to become the world’s first ‘National Park City,’ with a vision led by Mayor Sadiq Khan to plan from the premise ‘what if our cities were all natural landscapes?’ And Philadelphia, Chicago, Milwaukee, Atlanta, New York City, Detroit, and Vancouver are all implanting forms of green infrastructure plans. These plans explore new sources of investment and outline incentives to encourage the adoption of green initiatives towards increasing the tree canopy, ensuring residents have easier access to greenspace and increasing the acres of park per resident.

By operating from a framework of the city as nature, we have the opportunity to nurture a healthier and more equitable future for all—not just some—citizens of the city

It’s going to take a different way of thinking about and advocating for green space with architects, urban planners, urban designers, landscape architects and engineers all working in tandem. Moving toward this greener future will also require cross-disciplinary partnerships and alliances across city departments (bringing together public health, parks and recreation, utilities, sustainability and resilience), levels of local and federal government, in partnership with the nonprofit and philanthropic sector, and private development. And—most importantly—in getting community buy-in for both the vision and stewardship of these spaces.

More from Author

NBBJ | Oct 3, 2024

4 ways AI impacts building design beyond dramatic imagery

Kristen Forward, Design Technology Futures Leader, NBBJ, shows four ways the firm is using AI to generate value for its clients.

NBBJ | Jun 13, 2024

4 ways to transform old buildings into modern assets

As cities grow, their office inventories remain largely stagnant. Yet despite changes to the market—including the impact of hybrid work—opportunities still exist. Enter: “Midlife Metamorphosis.”

NBBJ | Oct 18, 2023

6 ways to integrate nature into the workplace

Integrating nature into the workplace is critical to the well-being of employees, teams and organizations. Yet despite its many benefits, incorporating nature in the built environment remains a challenge.

NBBJ | May 8, 2023

3 ways computational tools empower better decision-making

NBBJ explores three opportunities for the use of computational tools in urban planning projects.

NBBJ | Jan 17, 2023

Why the auto industry is key to designing healthier, more comfortable buildings

Peter Alspach of NBBJ shares how workplaces can benefit from a few automotive industry techniques.

NBBJ | Aug 4, 2022

To reduce disease and fight climate change, design buildings that breathe

Healthy air quality in buildings improves cognitive function and combats the spread of disease, but its implications for carbon reduction are perhaps the most important benefit.

NBBJ | Feb 11, 2022

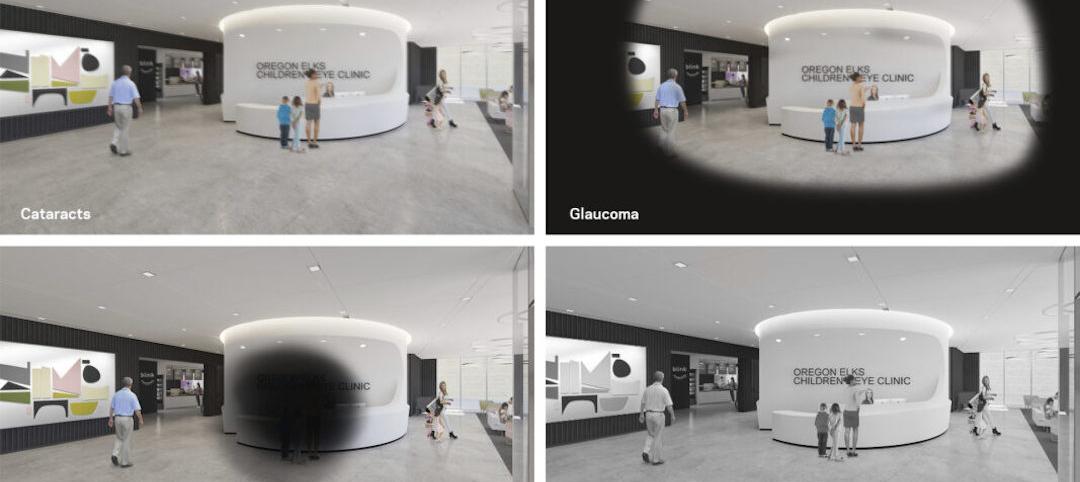

How computer simulations of vision loss create more empathetic buildings for the visually impaired

Here is a look at four challenges identified from our research and how the design responds accordingly.

NBBJ | Jan 7, 2022

Supporting hope and healing

Five research-driven design strategies for pediatric behavioral health environments.

NBBJ | Nov 23, 2021

Why vertical hospitals might be the next frontier in healthcare design

In this article, we’ll explore the opportunities and challenges of high-rise hospital design, as well as the main ideas and themes we considered when designing the new medical facility for the heart of London.

NBBJ | Aug 18, 2021

20 years after developing the first open core hospital design here is what the firm has learned

Hospitals have traditionally used a “racetrack” layout, which accommodates patient rooms around the exterior and situates work areas and offstage functions in a central block.