About five or six years ago, officials at the University of California at Berkeley came to the conclusion that they needed to build a proper home for the university's collection of 900,000 rare Chinese, Japanese, and Korean books and materials. East Asian studies is an important curriculum at Berkeley, with more than 70 scholars teaching some 200 courses devoted to the topic, and Berkeley's program has been ranked first in the nation by the U.S. Department of Education.

About five or six years ago, officials at the University of California at Berkeley came to the conclusion that they needed to build a proper home for the university's collection of 900,000 rare Chinese, Japanese, and Korean books and materials. East Asian studies is an important curriculum at Berkeley, with more than 70 scholars teaching some 200 courses devoted to the topic, and Berkeley's program has been ranked first in the nation by the U.S. Department of Education.So it was that, in 2005, the university commissioned the New York firm of Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (TWBTA) to design the C.V. Starr East Asian Library, with San Francisco's Tom Eliot Fisch as associate architect and McCarthy Building Companies as general contractor.

Williams and Tsien invested the project with the dynamism and flair that have made them stars in the architectural firmament. For the exterior, they specified thousand-pound bronze grilles made in Shanghai using a millennium-old sand-casting process. Blue bathroom tiles were hand-crafted by an artist in Sausalito. Some of the furniture was made from the highest-quality Canadian cherry. The bronze and stainless-steel donor plaques alone cost $200,000.

To stay within budget, though, the designers specified concrete for the exterior walls and special interior effects. As we shall see, this would be no routine concrete job. At every turn, Williams and Tsien kept upping the ante for McCarthy, subcontractor McClone Construction, and the rest of the Building Team. Let's look first at the exterior.

On the outside: Perfect walls, perfect angles

Building a 30-foot concrete wall is usually a pretty straightforward task, says Paul Erb, McCarthy's project manager on the Berkeley job: set the forms, insert the rebar, pour the concrete, and wait for it to set; repeat every few feet.

When you strip the forms, however, you get horizontal construction joints every couple of feet or so. Ordinarily, that's no big deal, either because the designer can cover the joints with reveals, or because they're not that crucial to the design.

When you strip the forms, however, you get horizontal construction joints every couple of feet or so. Ordinarily, that's no big deal, either because the designer can cover the joints with reveals, or because they're not that crucial to the design.But Williams and Tsien were not going to put up with construction joints. They had a vision of a seamless polished wall, 30 feet high and 200 feet long on the north and south sides, 75 feet long east and west, with absolutely no visual defects. This requirement upped the ante considerably.

The trick, as Erb's team learned through trial and error after several months of experimentation, was to keep pouring concrete up the wall in such a way that the lower layers would set, but not enough to create a joint with the next layer of pour. In other words, there had to be some fluidity at the intersection for the new pour to blend with the old, while at the same time having enough set in the concrete below to bear the weight of the new pour. Otherwise, the forms would blow out, an unthinkable prospect when you're talking 30-foot-high forms. “The amount of pressure that concrete puts on formwork is tremendous,” says Erb. “It would have been a violent explosion.”

How they did it: “We timed each one of the trucks to make sure that when they placed the concrete, it had enough slump to mix with the previously poured concrete,” says Erb. A laborer would vibrate the concrete—a delicate task in this case, because if you drop the vibrator too low into the setting concrete, the vibrator can turn that mass liquid, opening up the possibility of a blowout.

Meanwhile, McCarthy's quality-control experts were kept busy monitoring the setup time practically to the second, physically checking the set of the concrete using probes, and timing deliveries of concrete against the outdoor temperature. To maintain the right color, glue content, and aggregate mix (the architects hand-picked the Bay Area's bluish-gray Clayton aggregate) from delivery to delivery, the mix from two trucks was blended and the concrete was poured using a pump truck.

But Williams and Tsien were not done. Ordinarily, concrete walls are chamfered at the base, which makes it easier to take the forms off, but the TWBTA gang insisted on sharp, 90° angles. Why? “They just don't like chamfers,” says Erb.

|

| Tod Williams and Billie Tsien's nettlesome "floating staircase." The slim, two-story wall is held in place by compression from the concrete staris. |

But the corners came out absolutely rectilinear, and the Building Team was able to breathe a sigh of relief—that is, until Williams and Tsien came up with their last request for the exterior: concrete emergency exit doors.

Yes, concrete doors, two of them, eight feet by three feet. Usually concrete doors are made from precast slabs mounted to a metal door, but Williams and Tsien wanted custom concrete doors that would vanish into the walls.

How they did it: The McCarthy team poured concrete horizontally into stainless-steel frames only 2½ inches thick and fitted the doors with custom hardware to meet emergency egress requirements. If you look at the library from the outside, it's almost impossible to tell where the doors are, says Erb.

On the inside: More hoops to jump through

As if the exterior concrete work was not dicey enough, Williams and Tsien threw two more curve balls at the Building Team for the interior work.

The first of these was the floor. Once again, the designers wanted a special effect, using the aggregate in the concrete to create a finish that resembled polished terrazzo. The solution was to pour a concrete/aggregate mix and shave an eighth-inch off the top of the floor (as they had done on the exterior walls) and polish it to a matte finish to create a variegated surface. Sounds simple, but it wasn't.

To meet this demand, Erb's team knew that they had to pour the concrete/aggregate mix in such a way that the rocks would not settle to the bottom (the floor is 16 inches deep in places); otherwise the aggregate would not be close enough to the surface to be shaved and polished, and you'd be left with polished concrete. The variegation effect would be lost.

How they did it: “The more you vibrate the mix, the more the rocks move down, so we had to monitor the vibration very carefully, to make sure the operator was being really consistent from area to area,” says Erb. “Otherwise, you'd get a huge variance in how the floor would look.”

The extra eighth-inch of concrete was also a crucial determination. The team could have poured an extra inch or two, but that would have made it physically impossible to polish down far enough to hit the rocks. The single eighth-inch had to be just right. “The architects loved it,” says Erb, a civil engineer and 12-year construction veteran, five of them at McCarthy.

But Williams and Tsien had one more trick up their sleeves. They wanted a “floating staircase” to rise through two levels in the middle of the library. This, too, proved difficult to accomplish.

How they did it: First, the team poured 60,000 pounds of concrete to create a slim “floating wall” between the first two levels, holding it in place temporarily—and somewhat precariously—with scaffolding. “We were a little nervous when we did that,” says Erb. “It's a lot of weight.”

The next step involved pouring stairs up one side of the wall, then switching sides and pouring stairs down the other side of the wall. “The stairs hold the wall up by compression,” says Erb. “The wall is floating in space.”

Since its opening in 2008, the $39 million library has been viewed as one of UC Berkeley's “standout buildings,” says Erb. It was so successful, in fact, that the university awarded McCarthy the contract on a $200 million multiuse biotech lab, with Erb, since promoted to project director, running the job.

Related Stories

Geothermal Technology | Jul 29, 2024

Rochester, Minn., plans extensive geothermal network

The city of Rochester, Minn., home of the famed Mayo Clinic, is going big on geothermal networks. The city is constructing Thermal Energy Networks (TENs) that consist of ambient pipe loops connecting multiple buildings and delivering thermal heating and cooling energy via water-source heat pumps.

Smart Buildings | Jul 25, 2024

A Swiss startup devises an intelligent photovoltaic façade that tracks and moves with the sun

Zurich Soft Robotics says Solskin can reduce building energy consumption by up to 80% while producing up to 40% more electricity than comparable façade systems.

Codes and Standards | Jul 25, 2024

GSA and DOE select technologies to evaluate for commercial building decarbonization

The General Services Administration and the U.S. Department of Energy have selected 17 innovative building technologies to evaluate in real-world settings throughout GSA’s real estate portfolio.

Great Solutions | Jul 23, 2024

41 Great Solutions for architects, engineers, and contractors

AI ChatBots, ambient computing, floating MRIs, low-carbon cement, sunshine on demand, next-generation top-down construction. These and 35 other innovations make up our 2024 Great Solutions Report, which highlights fresh ideas and innovations from leading architecture, engineering, and construction firms.

Smart Buildings | Jul 1, 2024

GSA to invest $80 million on smart building technologies at federal properties

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) will invest $80 million from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) into smart building technologies within 560 federal buildings. GSA intends to enhance operations through granular controls, expand available reporting with more advanced metering sources, and optimize the operator experience.

Building Technology | Jun 18, 2024

Could ‘smart’ building facades heat and cool buildings?

A promising research project looks at the possibilities for thermoelectric systems to thermally condition buildings, writes Mahsa Farid Mohajer, Sustainable Building Analyst with Stantec.

Concrete Technology | Jun 17, 2024

MIT researchers are working on a way to use concrete as an electric battery

Researchers at MIT have developed a concrete mixture that can store electrical energy. The researchers say the mixture of water, cement, and carbon black could be used for building foundations and street paving.

Contractors | Jun 4, 2024

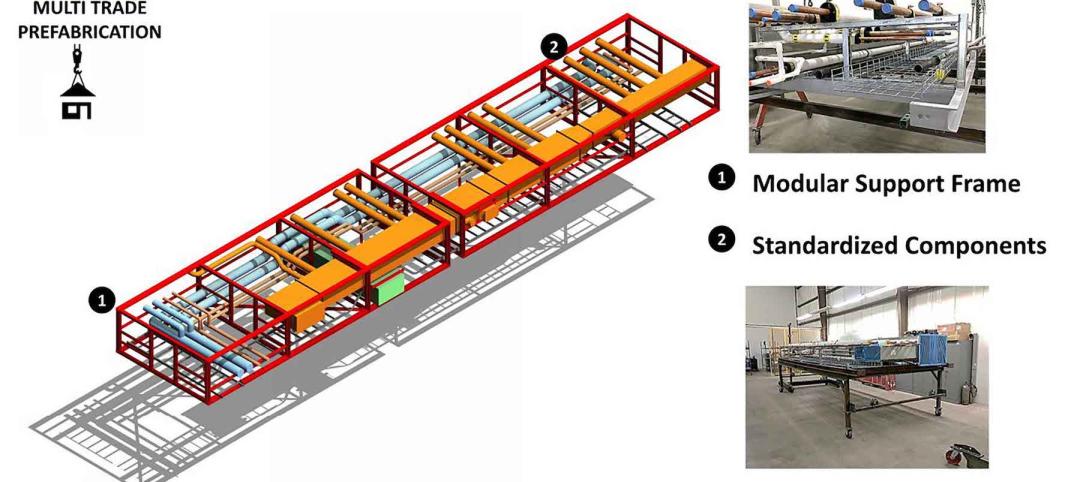

Contractors expect to spend more time on prefabrication, according to FMI study

Get ready for a surge in prefabrication activity by contractors. FMI, the consulting and investment banking firm, recently polled contractors about how much time they were spending, in craft labor hours, on prefabrication for construction projects. More than 250 contractors participated in the survey, and the average response to that question was 18%. More revealing, however, was the participants’ anticipation that craft hours dedicated to prefab would essentially double, to 34%, within the next five years.

MFPRO+ New Projects | May 29, 2024

Two San Francisco multifamily high rises install onsite water recycling systems

Two high-rise apartment buildings in San Francisco have installed onsite water recycling systems that will reuse a total of 3.9 million gallons of wastewater annually. The recycled water will be used for toilet flushing, cooling towers, and landscape irrigation to significantly reduce water usage in both buildings.

HVAC | May 28, 2024

Department of Energy unveils resources for deploying heat pumps in commercial buildings

To accelerate adoption of heat pump technology in commercial buildings, the U.S. Department of Energy is offering resources and guidance for stakeholders. DOE aims to help commercial building owners and operators reduce greenhouse gas emissions and operating costs by increasing the adoption of existing and emerging heat pump technologies.