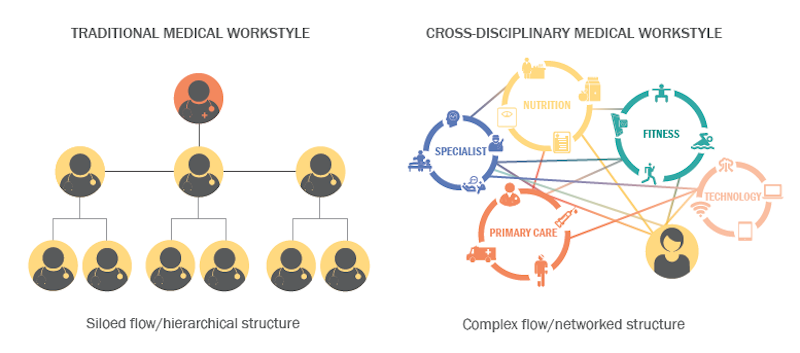

“Collaboration” has become an abiding design goal for many nonresidential building types, such as offices and educational institutions. But the medical field, with its hierarchical divisions and silo mentality among professionals, continues to resist a more collaborative workplace culture.

Perkins Eastman set out to find out why, and used one of its own projects—the 95,000-sf NYU Winthrop Hospital Research and Academic Center in Mineola, N.Y.—as a test case a year after it opened in 2015.

The firm's post-occupancy evaluation—whose findings it published in a recently released white paper “The Effectiveness of Collaborative Spaces in Healthcare and Research Environments”—focuses on the activities within a third-floor multi-use space in the facility that the firm designed specifically with employee interaction in mind.

The white paper touches on the evolution of collaborative design, and singles out two examples—Bell Labs’ headquarters in Murray Hill, N.J., in the 1960s, and Google’s national headquarters in Mountain View, Calif.—where cross-disciplinary collaboration took root and where “activity based” working is now on full display.

The paper notes that offices and education facilities are creating these kinds of environments by planning for collaboration early in the design process, “to include a variety of different kinds of areas to support one-on-one, individual, small group and large groupings.”

However, even the most thoughtfully designed space won’t lead to meaningful change in a workspace if it isn’t supported by policies and attitudes that foster collaboration. And that support is what Perkins Eastman found was missing at NYU Winthrop Research and Academic Center.

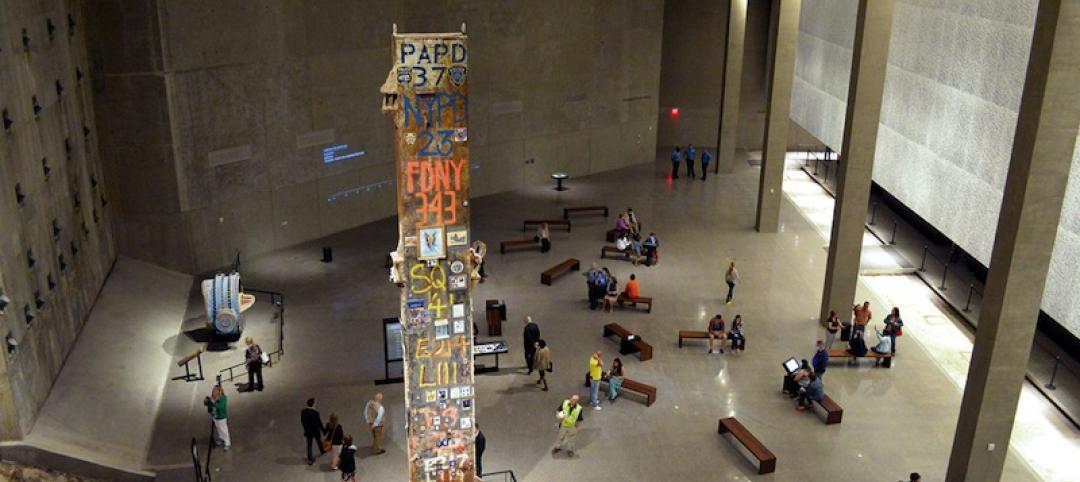

Its third-floor space was seen as a microcosm of Perkins Eastman’s design intent. Its programmatic elements include a pantry with small cook and prep area and two vending machines, a café dining space with tables and chairs, a break area with soft seating, a low four-person conference table and sit-up bar; a work room with a TV, tablet chairs and writable magnetic wall; a research area with a large writable wall, movable ottomans, and high-top tables and writing table tops; and a conference room with a large executive meeting table, digital projection capabilities, wet bar and seating banquette.

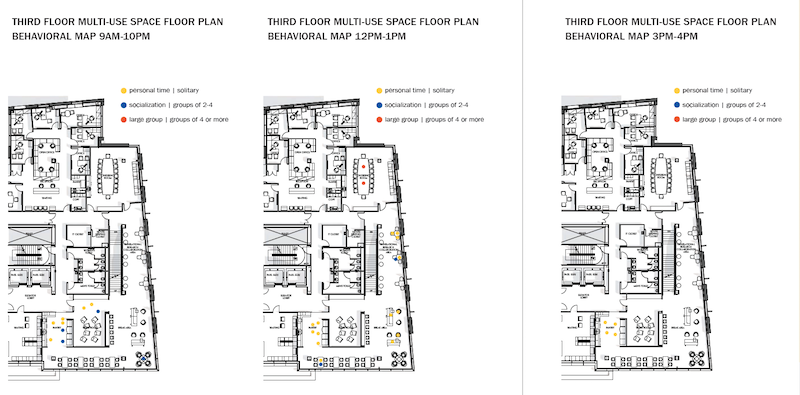

To assess employee engagement in a multi-use space within NYU Winthrop's Research and Academic Center, Perkins Eastman observed and place-mapped activities over a nine-hour period in several time intervals. It found scant indepartmental connectivity, and virtually no use of this space for work. Image: Perkins Eastman

Perkins Eastman observed and place-mapped employee interactions in that space over a nine-hour period in four intervals during the day. The firm tracked how long people spent in any one place, and what they were doing. It also noted whether people were alone or in groups.

“Very little interaction among users from different departments was observed,” Perkins Eastman found. Most people used to space to eat their lunches or talk on their phones. And they usually hung out with people from their own departments. “No spontaneous meetings of small or large groups were observed, and the amenities provided to support impromptu collaboration…went unused.”

Subsequent interviews with 17 user groups from various departments found that while employees generally like the space, they didn’t know how to use it other than to eat lunch or buy food from the vending machines.

None of the people interviewed used the space for work, primarily because their jobs require computers and other tools located at their designated workstations. More surprising, though, was the finding that many of the interviewees weren’t sure if they were even allowed to use the third-floor space for meetings or presentations. In fact, they were “simply uninformed about the potential uses of the third-floor space,” the white paper reports.

Perkins Eastman found that most doctors, researchers, nurses, and administrators within the user groups interviewed would like to collaborate. But a suggestive design wasn’t enough to instigate that interaction. “The faculty and staff needed to be shown how to use the third-floor in order to promote its use as a collaborative space.”

The white paper concedes that research often requires quiet, focused study supported by specialized workstations or lab equipment. And the need for privacy can be a barrier to collaborating in a healthcare environment.

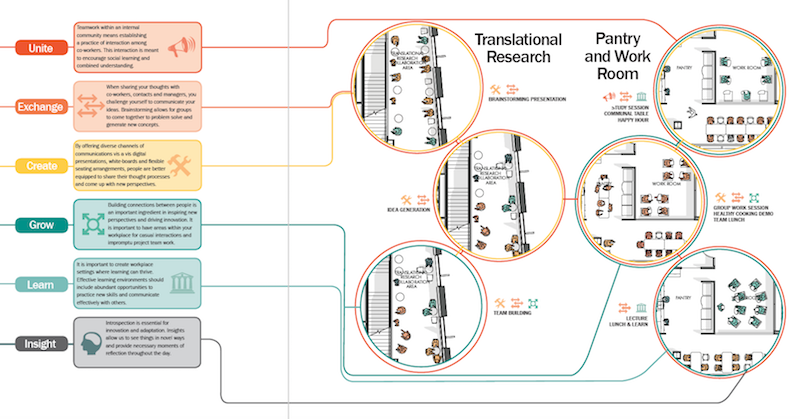

The white paper provides ways that medical centers could encourage collaborative use of their common spaces. The suggestions revolve around providing workers with more imformation about the potential uses of those areas. Image: Perkins Eastman

But there are “simple measures” that the Center could do to foment collaboration and communication, at least in the multi-use space with an open floor plan. These include:

•Create a schedule of programs and presentations for that space

•Assign an IT specialist to educate and assist users with technologies provided in the workroom and conference room

•Post information and signage that suggests how the space can be used

•Orient new employees about how to use the space, and

•Provide greater spatial variety, and the ability to close certain spaces for private meetings. (A number of interviewees said they didn’t conduct meetings on the third floor because none of the rooms could be closed off.)

In the final analysis, Perkins Eastman remains convinced that design, reinforced by programming, can support collaboration and employee engagement within a medical building. But the medical profession also needs to shift toward a more positive attitude about collaboration. “If users are uninformed about the potential uses of a space, it is difficult for a culture of collaboration to thrive.”

Related Stories

Healthcare Facilities | May 27, 2015

Rochester, Minn., looks to escape Twin Cities’ shadow with $6.5 billion biotech development

The 20-year plan would also be a boon to Mayo Clinic, this city’s best-known address.

Healthcare Facilities | Apr 28, 2015

10 things about Ebola from Eagleson Institute's infectious disease colloquium

Research institutions know how to handle life-threatening, highly contagious diseases like Ebola in the lab, but how do we handle them in healthcare settings?

Green | Apr 22, 2015

AIA Committee on the Environment recognizes Top 10 Green Projects

Seattle's Bullitt Center and the University Center at The New School are among AIA's top 10 green buildings for 2015.

Building Team Awards | Apr 10, 2015

14 projects that push AEC teaming to the limits

From Lean construction to tri-party IPD to advanced BIM/VDC coordination, these 14 Building Teams demonstrate the power of collaboration in delivering award-winning buildings. These are the 2015 Building Team Award winners.

Building Team Awards | Apr 10, 2015

Prefab saves the day for Denver hospital

Mortenson Construction and its partners completed the 831,000-sf, $623 million Saint Joseph Hospital well before the January 1, 2015, deadline, thanks largely to their extensive use of offsite prefabrication.

Building Team Awards | Apr 10, 2015

Virtual collaboration helps complete a hospital in 24 months

PinnacleHealth needed a new hospital STAT! This team delivered it in two years, start to finish.

Building Team Awards | Apr 9, 2015

Big D’s billion-dollar baby: New Parkland Hospital Tops the Chart | BD+C

Dallas’s new $1.27 billion public hospital preserves an important civic anchor, Texas-style.

Building Team Awards | Apr 9, 2015

‘Prudent, not opulent’ sets the tone for this Catholic hospital

This Building Team stuck with a project for seven years to get a new hospital built for a faithful client.

Healthcare Facilities | Apr 8, 2015

Designing for behavioral health: Balancing privacy and safety

Gensler's Jamie Huffcut discusses mental health in the U.S. and how design can affect behavioral health.

Building Team Awards | Apr 5, 2015

‘Project first’ philosophy shows team’s commitment to a true IPD on the San Carlos Center

Skanska and NBBJ join forces with Sutter Health on a medical center project where all three parties share the risk.