The United Nations estimates that by 2050 nearly 10 billion people will inhabit the planet, including 6.5 billion living in cities. That would be double the number of urban dwellers today. This population explosion is going to require different modes for growing and distributing food, in terms of yield, land and water use, and nutritional value, because right now, “the field isn’t meeting the needs of the customer globally.”

That indictment comes from Matt Barnard, CEO of Plenty, an agriculture tech firm that is among a handful of companies operating “vertical farms.” These indoor facilities rely on artificial light and aeroponic technology in a controlled environment in place of fresh air, soil, and pesticides to grow leafy greens. They require only a fraction of the water used by a conventional outdoor farm to produce an exponentially higher yield per acre.

Vertical farms could be on the verge of having their moment in the sun at a time when urban farming in general is an emerging phenomenon that accounts for between 15% and 20% of the world’s food supply, according to U.N. estimates. Big outdoor farms, which represent only 3% of the two million farms in total, still account for 42% of the value of production. But several states have passed legislation that encourages a more localized approach to growing.

In 2009, Illinois set a goal that 20% of all food products purchased by state agencies and state-owned facilities be supplied by local farms by 2020. The District of Columbia allocated $400,000 in 2016, and $350,000 in each fiscal year thereafter, to implement the District’s Urban Farming and Gardens Program. In 2016, Minnesota proposed spending $20 million over two years for agricultural research that includes developing urban farms.

In November, U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur proposed the Urban Agriculture Production Act of 2017, which would provide more federal assistance to help city farms boost local food production in places like Toledo, Ohio, where the availability of nutritious produce has been lacking.

Vertical farms that grow leafy vegetables indoors are attracting more attention from the press, investors, and grocers. These 24/7 farms include Plenty, whose 50,000-sf, environment-controlled indoor farm in South San Francisco grows its plants from 20-foot-tall vertical poles through which water and nutrients are fed. LED fixtures across from the poles provide lighting. Courtesy Plenty.

Vertical farms that grow leafy vegetables indoors are attracting more attention from the press, investors, and grocers. These 24/7 farms include Plenty, whose 50,000-sf, environment-controlled indoor farm in South San Francisco grows its plants from 20-foot-tall vertical poles through which water and nutrients are fed. LED fixtures across from the poles provide lighting. Courtesy Plenty.

Tech makes INDOOR farming feasible

Technology has always played a role in farming, and the advent of urban farming is no different. In an article he wrote in 2016 for National Geographic, Caleb Harper, Director of MIT Media Lab’s Open Agriculture Initiative, said his team was developing digital farming through a “food computer,” which combines aeroponic technology with sensors to monitor a plant’s water, nutrient, and carbon needs to deliver optimal light wavelengths that help create climates that yield the best vegetable and fruit flavors.

“We are a tech company that is thinking about the future of food,” Irving Fain, CEO and Co-founder of Bowery Farming, told Forbes last summer. Bowery’s vertical farm in Kearney, N.J., uses proprietary software to analyze data points that might impact a plant’s growth rate and flavor. Bowery’s growing method focuses on large-scale volume and yields 100 times more than a conventional outdoor farm per acre, while using only 5% of the water.

So far, Bowery—whose customers include Whole Foods and Foragers Market in Brooklyn—has raised $27.5 million from investors. The company sees both domestic and overseas expansion opportunities.

Another expanding vertical farmer is Aerofarms, which got its start out of a kayak shop in Ithaca, N.Y., in 2004. The Newark, N.J.-based company, which reportedly has raised more than $100 million from investors, will open its 10th farm inside a 78,000-sf building in Camden, N.J., later this year. The company received an $11 million tax incentive for this redeveloment from the New Jersey Economic Development Authority. By 2020, Aerofarms plans to be operating more than 25 vertical farms.

At the company’s 69,000-sf vertical farm in Newark—which opened in 2016 and doubles as its headquarters—grow tables are stacked 12 layers tall to a height of 36 feet, in rows 80 feet long. This aeroponic system germinates seeds within 12 to 48 hours. Aerofarms claims its vertical farms use 95% less water than conventional farms, and yield 130 times more produce per acre. The Newark farm yields two million lb of greens per year.

Last year, Aerofarms entered into a partnership with Dell Technologies, and is using Dell’s software to track its plant performance from seed to packaging.

Bowery Farming’s vertical farm in Kearney, N.J., grows its plants in horizontal, stacked aeroponic trays. Photo: Courtesy Bowery Farming.

Bowery Farming’s vertical farm in Kearney, N.J., grows its plants in horizontal, stacked aeroponic trays. Photo: Courtesy Bowery Farming.

Vertical farms rise as LED costs drop

One of the main reasons why vertical farming makes financial sense today is the dramatic reduction in the cost of LED lighting, which is essential to providing the artificial light these farms need to grow plants.

“Seven years ago, it would have cost us 64 times more to buy the light capacity we need today,” says Plenty’s Barnard. His company’s 50,000-sf farm in South San Francisco relies on 7,500 infrared cameras and 35,000 sensors embedded among the greens that monitor the room’s temperature, humidity, and growing phases. The data generated by these tools helps Plenty adjust the indoor environment to improve productivity and food taste.

Plenty takes a different approach to growing than its competitors. It uses 20-foot-tall vertical poles, lined up a few inches from each other. Software controls the nutrients and water that are fed through these poles, and leafy greens grow out of them horizontally. LED lights across from the poles provide the lighting. All of this is happening inside a building that is practically clinical in its attention to removing dust and contaminants.

Plenty operates a smaller demonstration farm in Laramie, Wyo., which came to Plenty as part of its June 2017 acquisition of Bright Agrotech. Plenty recently signed a lease on a building in Kent, Wash., that it plans to convert into a 100,000-sf vertical farm by the end of next year. It claims that the Kent farm, on approximately 2.5 acres, would yield 4.5 million lb of lettuce annually, compared to 15,000 lb per acre from field production.

Barnard declined to identify any AEC firms his company is working with. He’s also reticent about revealing his company’s growth plans outside of Plenty’s general goal of eventually placing a farm of between 100,000 sf and 250,000 sf in every city in the world with at least one million people—some 500 farms worldwide.

Barnard needs no prompting to talk about why vertical farming is filling in the gaps of conventional farming. His argument goes like this: The U.S. represents 4% of the world’s population, but consumes between 25% and 30% of the fruits and vegetables the world produces. Domestic production isn’t keeping up with demand: growers outside of the country currently provide 35% of what Americans eat. Fruits and vegetables grown domestically (much of which in California and Arizona) are often shipped 2,000 miles or more to reach store shelves. Some produce, like carrots, sits in storage for nine months. This means vital nutrients are being lost, and a good portion of food is thrown away because it spoils. Barnard claims that 50% of the calories grown in the field gets tossed in the U.S.

Vertical farms, on the other hand, provide a more efficient, localized solution. Plenty claims its farms can yield 350 times that of a comparable field acre, but require only 1% of the water. Because of their controlled environments and proximity to customers, vertical farms can deliver a tastier, fresher, and more nutritious product.

Bowery’s ability to create ideal growing conditions in a small indoor space depends on an integrated technology system. Grocers that buy produce from Bowery include Whole Foods and Foragers Market. Photo: Courtesy Bowery Farming.

Bowery’s ability to create ideal growing conditions in a small indoor space depends on an integrated technology system. Grocers that buy produce from Bowery include Whole Foods and Foragers Market. Photo: Courtesy Bowery Farming.

Not a zero-sum game

Barnard’s pitch has won over investors that include funds controlled by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Google’s Eric Schmidt. Last July, Japan’s SoftBank Group invested a whopping $200 million in Plenty.

But the vertical farm arena has seen its share of busts. And those companies that have made it so far have yet to demonstrate they can grow anything other than leafy greens. (Barnard says Plenty has plans to explore growing strawberries and cucumbers by early 2018.)

While projected yields from vertical farms may be impressive, what remains to be seen is whether these companies can expand and make money. (Plenty has stated that it is ramping up to where it could build two to six farms per month.)

Some observers are also concerned that vertical farming will further minimize the need for human labor in an industry that, despite relentless automation, still accounts for 11% of U.S. jobs.

When Aerofarms opened its indoor farm in Newark, it created 78 jobs. And Barnard predicts that, depending on the market and the size of the facility, Plenty’s farms would employ between 50 and 300 people.

Barnard wants to steer the conversation about vertical farms away from the perception that they threaten conventional outdoor farming. “This isn’t a zero-sum game,” he says. “We’re adding to capacity, not taking away from what’s being grown in the field.”

Related Stories

Game Changers | Jan 15, 2018

Innovation studio sparks AEC startups

Autodesk’s BUILD Space gives AEC firms and research teams free use of a robust collection of fabrication equipment and software expertise.

Game Changers | Jan 12, 2018

‘Kit of parts’ anchors university’s remake

Sasaki designs interchangeable spaces to support a major educational shift at Mexico’s largest university system.

Game Changers | Dec 20, 2017

Urban farms can help plant seeds for cities’ growth around them

Urban farms have been impacting cities’ agribusiness—and, on some cases, their redevelopment—for decades.

Mixed-Use | Aug 30, 2017

A 50-acre waterfront redevelopment gets under way in Tampa

Nine architects, three interior designers, and nine contractors are involved in this $3 billion project.

Projects | Jan 25, 2017

Trump prioritizes infrastructure projects, as rebuilding America is now a hot political potato

Both parties are talking about $1 trillion in spending over the next decade. How projects will be funded, though, remains unresolved.

Game Changers | Jan 19, 2017

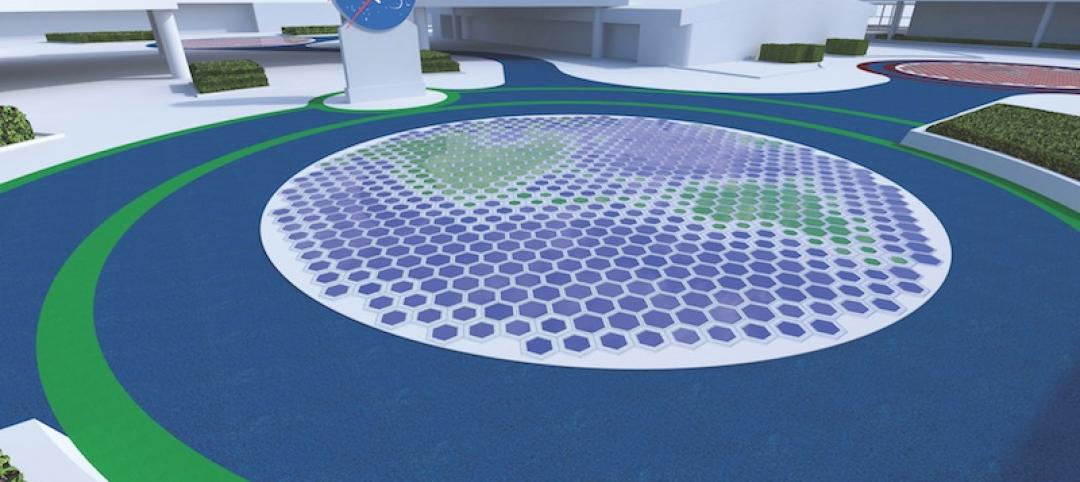

Piezoelectric hits the road

GTRI recently got the OK from the Georgia Department of Transportation to test embedded PZ material supplied by Tencate in a stretch of road and rest stop surfaces at West Point, Ga.

Game Changers | Jan 18, 2017

Turning friction into power

Research on piezoelectricity moves closer to practical applications for infrastructure and buildings.

Game Changers | Jan 13, 2017

Building from the neighborhood up

EcoDistricts is helping cities visualize a bigger picture that connects their communities.

Game Changers | Jan 12, 2017

Mass timber: From 'What the heck is that?' to 'Wow!'

The idea of using mass timber for tall buildings keeps gaining converts.

Game Changers | Feb 5, 2016

TIMELINE: 52 game-changing buildings through the years

From the E.V. Haughwout Building (first passenger elevator) to the Sackett-Wilhelms printing plant (first building with modern AC), BD+C editors present a timeline of the pacesetting projects from the past 170 years.