Thomas Edison relocated his headquarters operations from New York City to the leafy climes of West Orange, N.J., in 1887. There, 25 miles west of the city, he purchased Glenmont, a 29-room Queen Anne–style mansion for his family, and built his third—and grandest—laboratory, his “Invention Factory,” where he pledged to create “something useful every week” and “a big idea every six months.”

Until his death in 1931, Edison earned more than half of his 1,093 patents at this lab, perfecting the phonograph, refining the process for making Portland cement, and inventing the kinetographic camera. He and his R&D staff of more than a hundred also conducted more than 50,000 experiments in pursuit of a new kind of storage battery.

It was the battery that drew me back to West Orange on something of a sentimental journey. More than 20 years ago, I reported on the effort to preserve the first “corporate” R&D lab in the world (BDCnetwork.com/EdisonLab). Happily, the beautifully restored Edison National Historical Park is prospering under the guardianship of the U.S. National Park Service. At West Orange Edison also built factories to produce his phonographs and other inventions. At one time, he employed 10,000 in the town, and claimed his workers could “build everything from a lady’s watch to a Locomotive.”

Three connected buildings adjacent to the lab housed the more than 800 men and women who manufactured the “A4,” the first nickel-iron alkaline storage battery, which was originally used to power delivery trucks. By the 1930s, the plant was producing a million such batteries a year. Production continued (under the Exide brand) as late as 1965.

But by 2003, the 400,000-sf property, known as the Thomas Edison Invention Factory and Commerce Center, had turned into an eyesore housing 25 mom-and-pop businesses and manufacturing operations. Desperate to remove the blight in its midst, West Orange designated 21 acres in and around the battery plant—the last vestige of Edison’s once-sprawling manufacturing complex—as a redevelopment site.

Left, a bedroom in the model for The Residences at Edison Lofts. Ceiling heights of 14 to 16 feet prevail in the 279 apartments and 21 penthouses. The 635-foot-long leg of the factory building can be seen through the window. Below, a typical kitchen/living room open floor plan in the model unit. Photos: Prism Capital Partners

Progress on redevelopment was glacial, to say the least. “The town had been trying to find a developer for five years,” said Edwin H. Cohen, Principal Partner, Prism Capital Partners. “Nobody wanted to take the plunge, and the town was reluctant to use eminent domain.”

Cohen and Principal Partner Eugene Diaz were already certified for other development work in the town. They approached the authorities with a plan to build new retail space and new residential units and convert the battery factory into condominiums. (At the time, West Orange would not approve rentals.) In late 2006, the town named Prism Capital Partners as developers for “Edison Village.” Cohen and Diaz bought the battery property and completed demolition and site work in 2008.

Then the housing market crashed.

REGROUPING AFTER THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

Flash forward to late 2012. With the Great Recession behind them, Cohen and Diaz were able to gain final approval from the town for a phased, mixed-use development, this time for apartments—only to be stalled by a lengthy but ultimately unsuccessful challenge by local taxpayers who objected to the use of $6.3 million in municipal bonds to cover the project’s infrastructure costs.

Finally, in early 2016, Prism, partnering with Dune Real Estate Partners and Greenfield Partners, secured a $70 million construction loan for the entire Edison Lofts project, starting with The Mews at Edison Lofts: 34 one- and two-bedroom apartments (746 to 1,336 sf), 18,400 sf of retail, and a 630-space garage—all new construction—which was completed in 2017.

Next came the renovation of the battery factory, three unadorned, reinforced cast-in-place concrete buildings of column and beam construction, designed by Edison’s draftsmen and built from 1909 to 1914. The style of the structures, described as “utilitarian in nature,” was much admired by European architects of the time for its very lack of ornamentation, as well as for the large, unadorned windows, which let in plenty of light for the workers. The complex was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.

Because the buildings were continuously occupied until 2006 and then closed in by Prism, they were in relatively good shape—no water damage, no infestation. Even the flake plating building, where “great vats of acid and other chemicals” were used, wasn’t too badly damaged. “Luckily, Edison was a neatness freak,” said Jonathan F. Hoff, CPM, RPA, Senior Vice President, Prism Property Services. The usual culprits, asbestos and lead, were easily subdued by Prism Construction Management, which self-performed all construction.

Prism Construction also treated the spalling in the concrete façade and tested 50 colors to match the pinkish-tan original. (The International Concrete Repair Institute later honored this work with its “Repair Project of the Year” award.) “Our agreement with the town was to replicate what in theory the buildings looked like when Edison built them,” said Cohen.

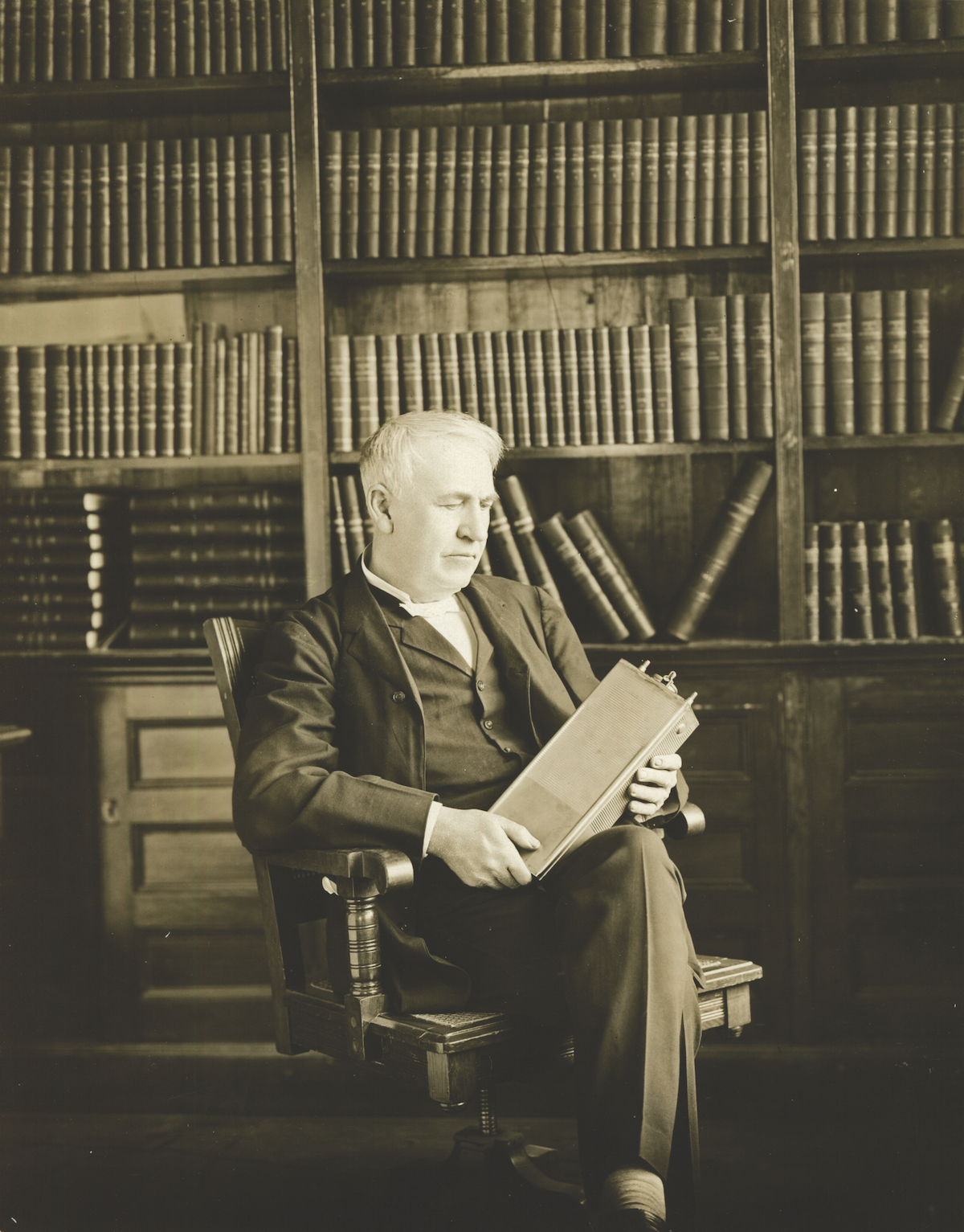

Edison with a Type A4 Edison cell, the nickel-iron alkaline storage battery produced at his factory in West Orange, N.J. Left,

‘WOOD WILL ROT, STONE WILL CHIP AND CRUMBLE, BRICKS DISINTEGRATE,

BUT A CEMENT AND IRON STRUCTURE IS APPARENTLY INDESTRUCTIBLE.’

—THOMAS A. EDISON, 1847–1931

The most nettlesome problems had to do with the structural geometries of the buildings, whose floor heights shifted as much as 12 feet from one side to the other. There was also the differences in ceiling heights—anywhere from 14 to 16 feet—for which the project architect, David J. Minno, AIA, PP, Principal of Minno & Wasko Architects and Planners, had to devise 40 different floor plans to create loft apartments suitable for the market.

The egress patterns for the existing stairs failed to meet state code, so all the stairs had to be relocated, a process that was complicated by the crazy changes in elevation. “They’re the hardest stairs I’ve ever built,” said Stephen Torell, PE, LEED AP, Senior Project Manager for Prism Construction. (Several times during our tour Hoff pointed out the windows in the stairwells, which provide daylighting and enhanced security. “That’s a feature you don’t see very often,” Hoff noted proudly.) Four new elevator shafts also had to be built and fitted with Schindler MRL (“machine room less”) elevators.

The business plan for the project called for 21 bi-level penthouses to be built atop the long leg of the main factory building, a six-story, L-shaped monolith longer than two football fields. “Rather than trying to mimic the original, we wanted to set the penthouses back from the building line to allow for terraces, as we had done at Parkway Lofts,” said Minno, referring to a 361-unit conversion of a General Electric warehouse in Bloomfield, N.J., which his firm had also designed for Prism. After extensive negotiations with the West Orange Historic Preservation Board, the concept was approved.

The penthouses had to be constructed over a vast space, 415 long and 60 wide. “The roof was sloped, so it took a maze of reinforced concrete beams and two to four feet of foam to fill the space between the beams and get a flat surface,” said Torell.

UPSCALE STYLE, CONVENIENT LOCATION

The reconstructed battery plant, known as The Residences at Edison Lofts, offers 21 penthouse units, plus 279 luxury studios and one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments (590 to 1,500 sf), renting from $1,750 to $4,500. The 34 units in “The Mews” are fully occupied, and leasing has been moving along “as planned” for the residences in the reconstructed battery factory, said Cohen. Rents are averaging $2.60/sf, a step up from most of the apartment stock in the area, said Hoff.

The complex is less than a 20-minute drive to Essex County College, Seton Hall University, New Jersey Institute of Technology, and the Newark campus and dental school of Rutgers University. It’s a 35- to 40-minute trip on NJ Transit to Penn Station in New York.

“The product offering in the units themselves is unique for this area, very upscale,” said Minno, who compared the interior style of the lofts, with their stratospheric ceiling heights and fully loaded amenities, to what might be found in a neighborhood like New York’s Tribeca.

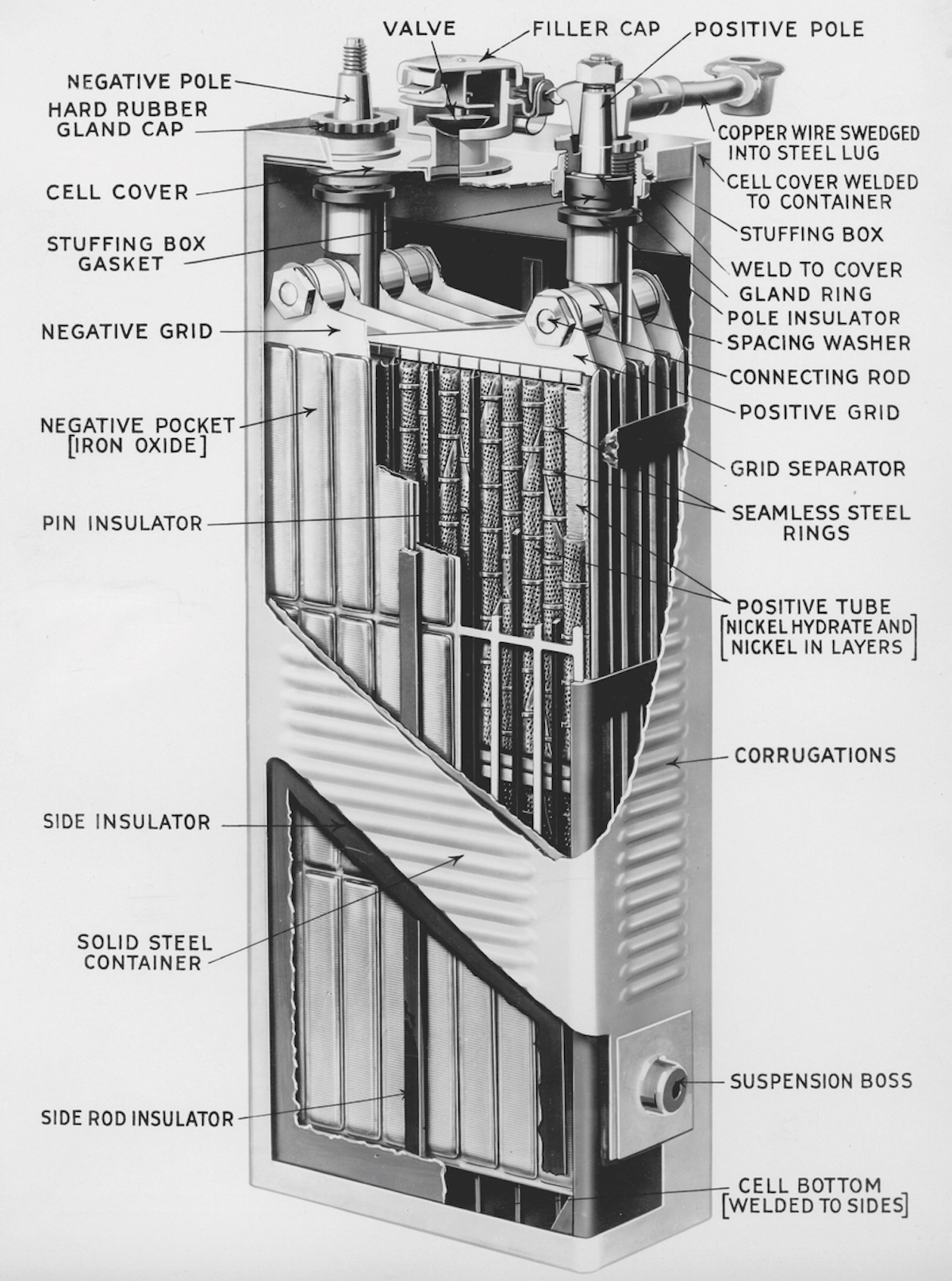

Top, the nickel-plating operation. Middle, the assembly room, where the "cells" were put together. Note the tall windows, which allowed a profusion of daylight to permeate the workers’ space. By the 1930s, the plant was producing more than a million A4s a year, and it became known as the “Million Cell Plant.” Bottom, schematic of the Edison A4 storage battery, which was manufactured in similar form until 1965.

The entire project was built to LEED standards, but Prism passed on certification. “We didn’t want to pay all that money for a plaque,” said Cohen. Energy-efficient double-pane windows from Graham Architectural Products—2,450 in total, 798 of which are 10 feet in height—were installed. Closed-cell spray foam insulation was applied to the interior of the exterior concrete walls to seal them and minimize air infiltration. Heat-recovery units and energy-recovery wheels were installed to save energy.

Each apartment has its own 95%-efficient split-system furnace and 16 SEER air-conditioner. Tenants pay for their own water, gas, and electricity. Metering each unit for electrical service was “pretty easy,” said Torell, but not so for the gas meters, which had to be ganged in three rooms in the lowest level.

LVT flooring was used throughout to save on maintenance and tenant turnover. “It’s great because I don’t have to recarpet every time I get a turn,” said Hoff.

WILL WONDERS NEVER CEASE?

Some finishing touches were still being contemplated during my visit last February. A plaza with fountain was being readied for spring installation. The commercial strip was just starting to be advertised for rental. Prism was in discussions with the museum to get a rotating display of Edison artifacts for the lobby.

Prism Capital Partners is already at work developing the remaining 20 or so acres across the way from Edison Lofts for 294 townhomes, 44 of which will be reserved as affordable units. That will bring the total budget for Edison Village to $230 million. The developer has also formed a partnership with Angelo, Gordon & Co. and Parkwood Development Corp. on the $120 million conversion of an 1909 Wonder Bread bakery (Wonder Bread’s slogan: “Builds strong bodies 12 ways”) in Hoboken that will yield 83 loft condominiums and six rentals.

PROJECT TEAM

THE RESIDENCES AT EDISON LOFTS, West Orange, New Jersey

OWNER/DEVELOPER Prism Capital Partners, in partnership with Dune Real Estate Partners and Greenfield Partners

PROPERTY MANAGER Prism Property Services

ARCHITECT Minno & Wasko Architects and Planners

CONSTRUCTION MANAGER/GC Prism Construction Management

NO SPARING THE AMENITIES

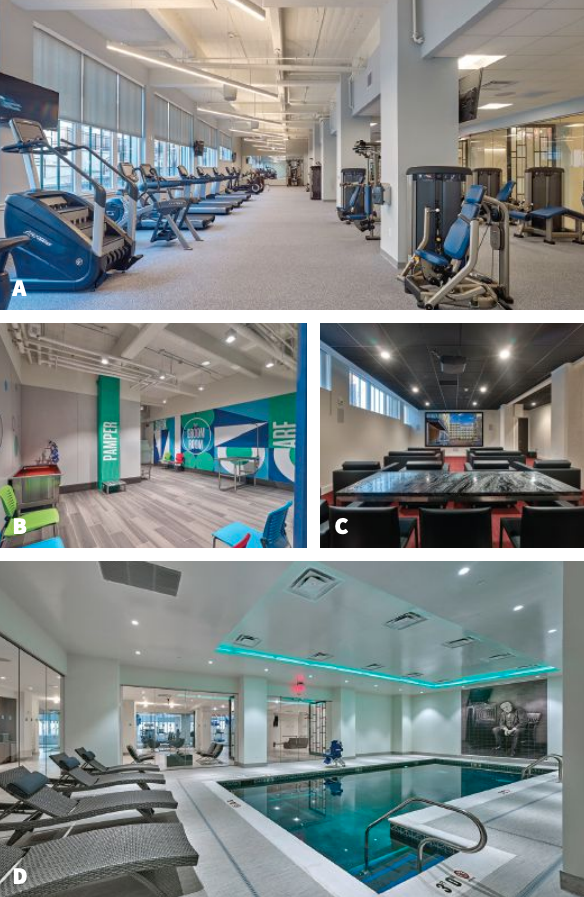

Prism Capital Partners’ Ed Cohen said the decision to switch from condo to rental meant there could be no sliding on the extras for Edison Lofts. “We knew from experience with Parkway Lofts [a previous project] that to successfully market the property, we had to offer a high level of finishes and amenitize it to hell.” Here’s how they did that:

• 7th-floor Sky Lounge (12,000 sf; capacity: 102) with fire pit, chamfered bar, refrigerators, ice machine, garage-door opening to the 5,000-sf deck, view of Manhattan skyline

• 7th-floor private dining room with kitchenette, view of NYC skyline

• Quartz countertops and backsplashes in all kitchens

• AyA cabinetry, LVT flooring throughout

• Bosch, Samsung appliances

• 5,000-sf fitness center with Peleton, spin bikes, yoga space, Life Fitness gym equipment (A)

• Dog spa (“The Groom Room”) (B)

• 21-seat soundproof media room (C)

• 11-seat soundproof theater room

• 4½-foot-deep indoor pool and sauna (D)

• All units prewired for fiber-optic service (Xfinity and AT&T)

• 60 storage units for tenant rental (4x5 to 9x6 feet)

• Laundry room with heavy-duty appliances (for bedding, throw rugs, coats, etc.)

• Refuse room with green recycling carts

• Secure indoor bicycle storage

• Library/reading area

Related Stories

Multifamily Housing | Mar 15, 2017

Amenity-packed residential building is Zaha Hadid’s only NYC project

The building sits adjacent to New York’s popular High Line park and includes a $50 million penthouse.

Sponsored | Multifamily Housing | Mar 10, 2017

Bathroom ergonomics and design for a shifting demographic

Multifamily Housing | Feb 24, 2017

121 East 22nd Street will be the first OMA-designed residential building in NYC

The building will offer 133 units across its 18 stories.

Multifamily Housing | Jan 15, 2017

Multifamily sector expected to stay strong in 2017

Market watchers expect some moderation from record highs, but not much.

Game Changers | Jan 13, 2017

Building from the neighborhood up

EcoDistricts is helping cities visualize a bigger picture that connects their communities.

Multifamily Housing | Jan 11, 2017

Istanbul’s Valens Archway could be rejuvenated with “floating” housing concept

Superspace’s proposal would create a natural promenade atop the ancient stone structure.

University Buildings | Jan 9, 2017

Massive student housing project in Texas will be ready this Fall

Developers hope the early opening of some units sets the tone for the community and future rentals.

Multifamily Housing | Dec 22, 2016

Multifamily green financing programs grew rapidly in 2016

Multifamily green financing programs boomed in 2016, and are likely to continue to grow in 2017, according to the president of Partner Energy.

Market Data | Dec 21, 2016

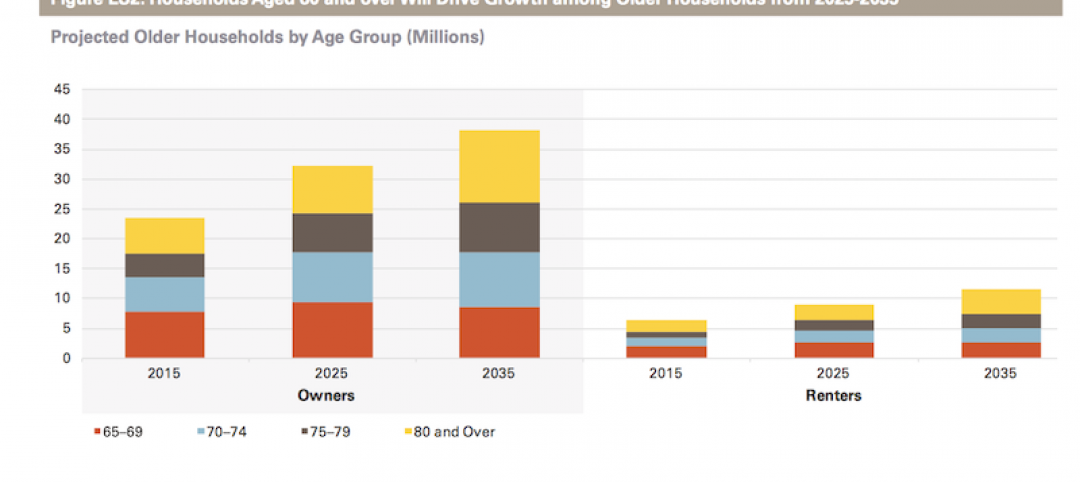

Will housing adjust to an aging population?

New Joint Center report projects 66% increase in senior heads of households by 2035.