In the “Glass Box Paradox,” Paladino and Company contend that there is a causal relationship between the performance of the façade of One Bryant Park (OBP) and the building’s overall energy use. This is a massive over-simplification of the building’s energy profile. Furthermore, the authors rely on the flawed methodology of “Site Energy Use Intensity (Site EUI)”, which penalizes the use of cutting-edge sustainability features such as Co-Generation and Ice Storage and, ironically, discourages density and the sharing of resources in the name of environmentalism. And, most importantly, it ignores that buildings are places which should promote the health, welfare and productivity of the people who work and live in them.

First and foremost, OBP is a building designed for people. Productivity, wellness, and providing optimal conditions for work to occur, were all drivers of the design of the building. The mechanical systems and envelope were designed to efficiently support those goals. The authors provide some good ideas for how to modify a façade to make it more energy efficient. Most of their recommendations were considered when the building was designed and many incorporated into the final constructed envelope, including:

-

High-performance glazing: The curtainwall at OBP features low-iron, insulated glazing with a ceramic frit pattern which cuts down on heat gain while still allowing for optimal views and an abundance of daylight,

-

Envelope details:

- Fritted glazing, insulated spandrel

- Overall R-value: 2.03

- Glazing Percentage: 62% vision glass

- Solar Heat Gain Coeffcient (SHGC): 0.4 for clear, 0.28 for fritted glazing

- Visual Transmittance: 74% for clear, 59% for fritted glazing

-

Envelope details:

It is true that OBP, consumes more energy compared with other buildings of its size. This is related to the level of the fenestration in the building, but not caused by it. Even if OBP featured a highly insulated exterior wall assembly with tiny porthole windows it would still have high energy use. It would also be a very unpleasant and unproductive place to work. OBP’s high energy use is primarily caused by the density of people who work in the building, the energy intensive work they do, and the delivery and conditioning of air at a high quality level. The three most significant factors that contribute to the building’s energy use are:

- Occupancy: 8,000 people work at OBP, and the building operates nearly 24-hours a day. There is significant energy required to provide adequate outside air to ventilate the space and the plug-load for that density of use is large.

- Intensity of Use: There are 350,000 square feet of extremely high-density trading operations and on-site data storage, which consume a lot of energy.

- Outside Air Delivery and Conditioning: Tempering the air in a building with that many inhabitants and a high percentage of glazing does use considerable energy, but the benefits of highly filtered outside air provided at above code required levels are substantial.

Even though OBP may consume more energy, it produces less Carbon Dioxide than similar buildings that use less energy directly from the grid. OBP only appears more inefficient because Site EUI, rather than Source EUI, is the metric used to compare energy use. Site EUI is perverse metric, which hides the inefficiencies of the grid and power plants. Instead of drawing most of its energy from power plants, OBP has an on-site 4.6-Megawatt combined heat and power (co-generation) plant that produces two thirds of the building’s energy at twice the efficiency of a conventional power plant. OBP also employs the use of an on-site Ice Storage plant as a thermal battery that shifts energy demand to off-peak hours, reducing the burden on New York City’s energy grid and carbon emissions. It also protects New York City’s air quality by reducing peak demand on the grid and keeping dirtier “peaker” plants offline. The cogeneration system converts natural gas into electric and heat energy at an efficiency that surpasses that of the utility. Yet, the energy conversion losses borne by the cogeneration plant, despite the overall reduction of carbon, are attributed to OBP and raise the overall site EUI. If Source EUI were used to compare buildings rather than Site EUI then OBP would excel compared to buildings of similar use and typology that procure energy from the existing inefficient grid and its power plants.

See Also: The glass box paradox

The authors argue that despite its design and Platinum LEED rating, the building earns an Energy Star D rating and incorrectly concludes that the building performs poorly. Local law 84, which relies on Energy Use Intensity as its metric, is a simplistic formula that compares total annual energy over the total square footage. It does not account for population density, hours of operation, building typology, specialized space types (within the office category) or any other variable. The Energy Star rating which uses the national CBECS database to calculate the score is more sophisticated than EUI alone, but the Energy Star metric does not accurately represent New York City buildings. Buildings over 1 million square feet are considered “outliers” in the Energy Star sample set and other population and operational data is truncated. Large, densely occupied, high-rise buildings in New York City are obviously very different in their energy profile than many buildings across the nation. Local law 97, penalizes buildings based on their calculated carbon footprint, which is superficially reasonable until you realize that higher density and all its environmental benefits are strongly related to a higher site EUI. New York City’s density which results in sharing of resources, decreased travel distances and the preservation of open space is, ironically, discouraged by Local Law 97.

The Durst Organization has built some of the highest performing and most environmentally advanced buildings in the world. We use energy and natural resources efficiently, but we also understand that buildings are for people and their health, wellness and productivity are equally important. A building without fenestration, no doubt, uses less energy than a building with a glass curtain wall, but we strive to make places where people flourish and thrive and natural light, fresh air and views are integral to this goal.

Related Stories

Sponsored | | May 3, 2014

Fire-rated glass floor system captures light in science and engineering infill

In implementing Northwestern University’s Engineering Life Sciences infill design, Flad Architects faced the challenge of ensuring adequate, balanced light given the adjacent, existing building wings. To allow for light penetration from the fifth floor to the ground floor, the design team desired a large, central atrium. One potential setback with drawing light through the atrium was meeting fire and life safety codes.

| Apr 25, 2014

Recent NFPA 80 updates clarify fire rated applications

Code confusion has led to misapplications of fire rated glass and framing, which can have dangerous and/or expensive results. Two recent NFPA 80 revisions help clarify the confusion. SPONSORED CONTENT

Sponsored | | Apr 23, 2014

Ridgewood High satisfies privacy, daylight and code requirements with fire rated glass

For a recent renovation of a stairwell and exit corridors at Ridgewood High School in Norridge, Ill., the design team specified SuperLite II-XL 60 in GPX Framing for its optical clarity, storefront-like appearance, and high STC ratings.

| Apr 8, 2014

Fire resistive curtain wall helps The Kensington meet property line requirements

The majority of fire rated glazing applications occur inside a building to allow occupants to exit the building safely or provide an area of refuge during a fire. But what happens when the threat of fire comes from the outside? This was the case for The Kensington, a mixed-use residential building in Boston.

| Apr 2, 2014

8 tips for avoiding thermal bridges in window applications

Aligning thermal breaks and applying air barriers are among the top design and installation tricks recommended by building enclosure experts.

Sponsored | | Mar 30, 2014

Ontario Leisure Centre stays ahead of the curve with channel glass

The new Bradford West Gwillimbury Leisure Centre features a 1,400-sf serpentine channel glass wall that delivers dramatic visual appeal for its residents.

| Mar 13, 2014

Austria's tallest tower shimmers with striking 'folded façade' [slideshow]

The 58-story DC Tower 1 is the first of two high-rises designed by Dominique Perrault Architecture for Vienna's skyline.

| Mar 7, 2014

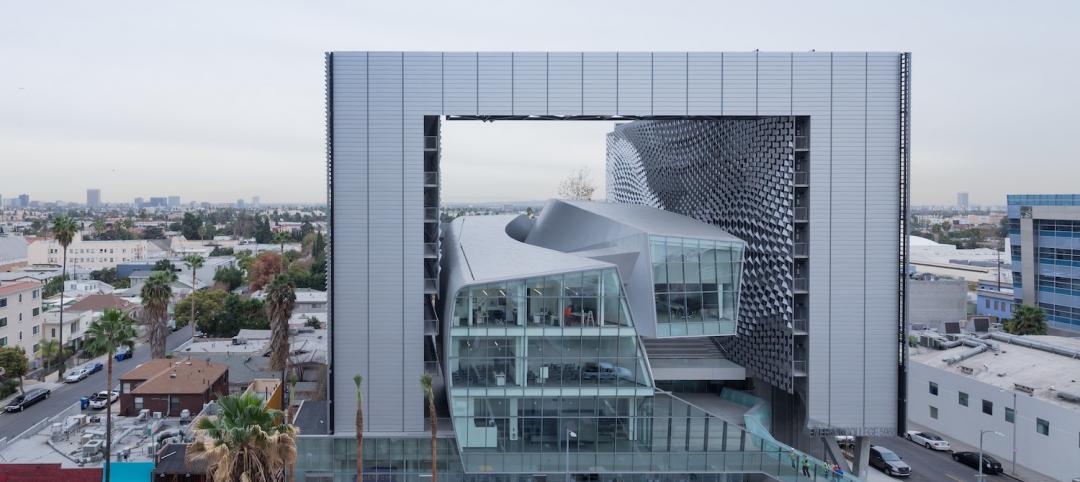

Thom Mayne's high-tech Emerson College LA campus opens in Hollywood [slideshow]

The $85 million, 10-story vertical campus takes the shape of a massive, shimmering aircraft hangar, housing a sculptural, glass-and-aluminum base building.

| Feb 27, 2014

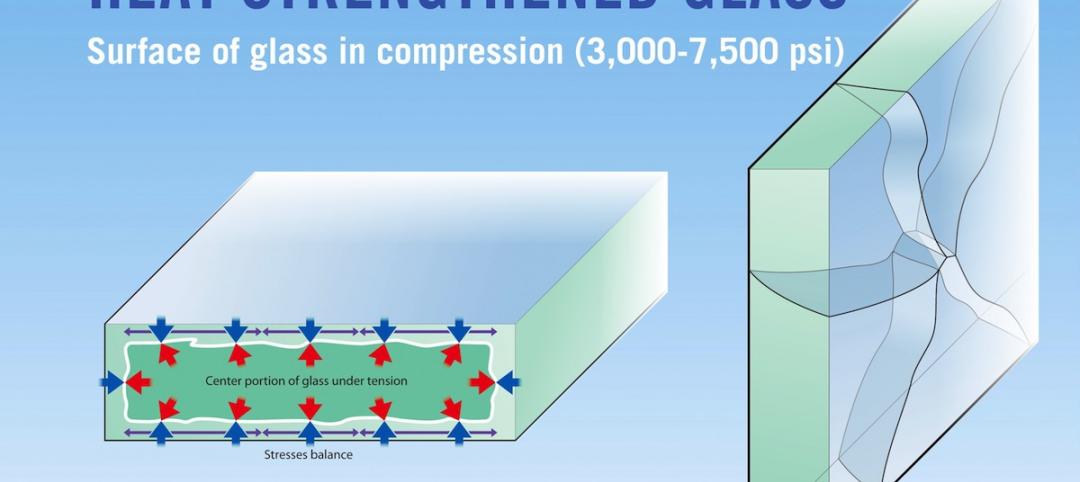

12 facts about heat-treated glass: Why stronger isn’t always better

Glass is heat-treated for two reasons: the first is to increase its strength to resist external stresses such as wind and snow loads, or thermal loads caused by the sun’s energy. The second is to temper glass so that it meets safety glazing requirements defined by applicable codes or federal standards.

| Feb 27, 2014

PPG earns DOE funding to develop dynamically responsive IR window coating Technology aims to maintain daylighting, control solar heat gain

PPG Industries’ flat glass business has received $312,000 from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to develop a dynamically responsive infrared (IR) window coating that will block heat in the summer to reduce air-conditioning costs and transmit solar heat in the winter to reduce heating costs.