Think about some architectural or landscaping elements that can add to a building’s character. Are they columns at the top of wide, limestone steps? Maybe some shade trees that drape over the sidewalk? Or an open, industrial stairway that rises up through a lobby? They’re all lovely gestures for sure, but San Francisco architect Chris Downey would like us to “see” those things without our eyes.

Universal Design Insights

Downey is blind. That means columns without setbacks, for instance, pose a (painful) greeting at the top of those steps. Low-hanging tree branches impede his path, even when his cane suggests an open sidewalk. Same thing with the cool floating stairway if he’s approaching from the side—the cane goes underneath it while he walks right into its I-beam stringer.

Downey spoke to the Perkins Eastman staff, just ahead of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, which is recognized globally each year on December 3. Downey revealed to the firm his world as a blind architect—and his mission to help sighted professionals think about design in new ways to provide beauty without barriers. “We’re architects,” he said. “We’re trained not to shrug away from challenges. We revel in the unknown. We revel in the exploration.”

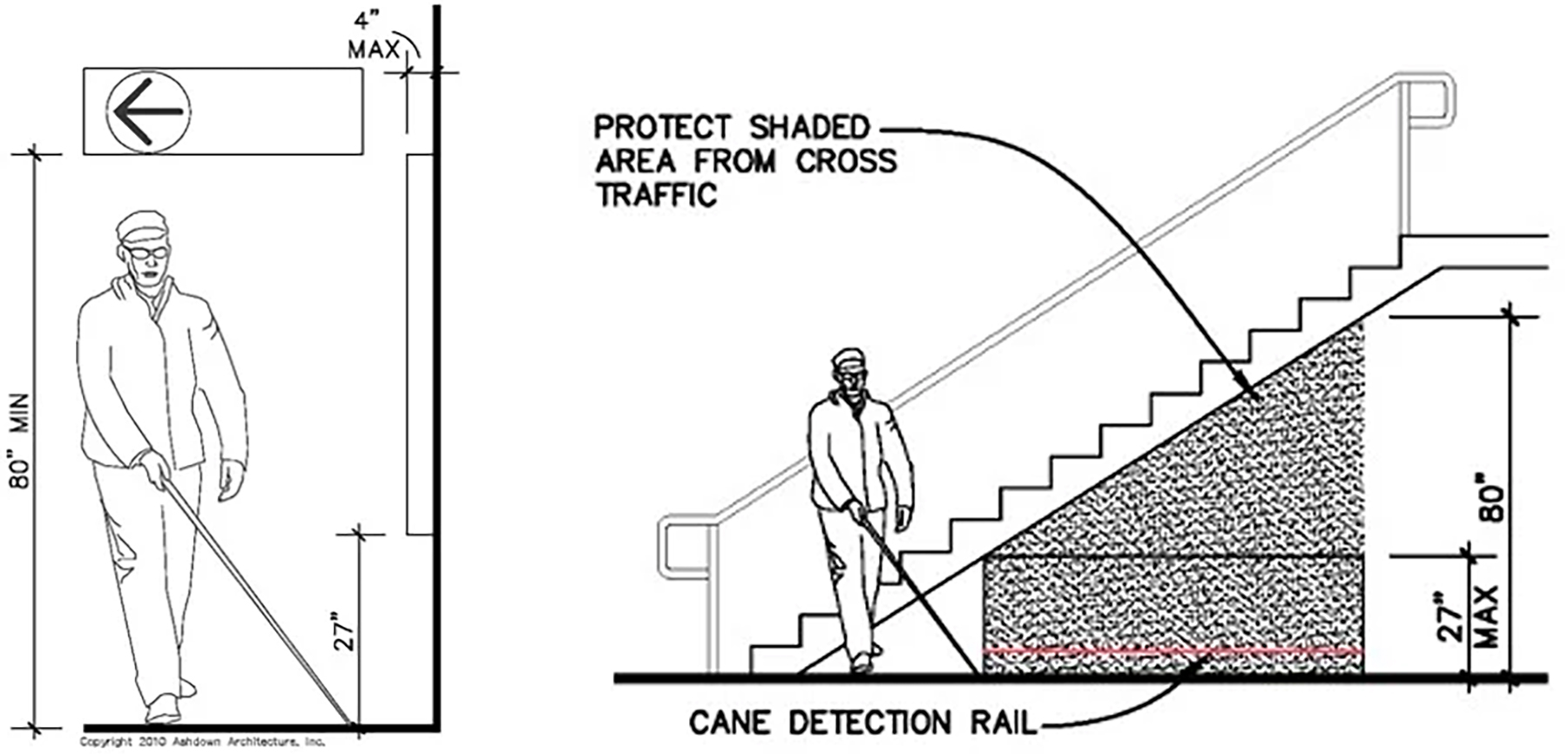

Downey was used to following code requirements before he went blind, he told Perkins Eastman, but once he became the man in the diagram, they developed a whole new meaning:

Downey has been exploring these unknowns since 2008, when he became blind following an operation to remove a brain tumor that was near his optical nerve. His journey has led him to believe there’s a beautiful power in disability. “We have to get away from the deficit model of disability,” he told the Perkins Eastman staff. “It can be additive. You can find new values, new possibilities,” rather than feel lost in the notion that 'I can’t.'”

Architecture Beyond Sight

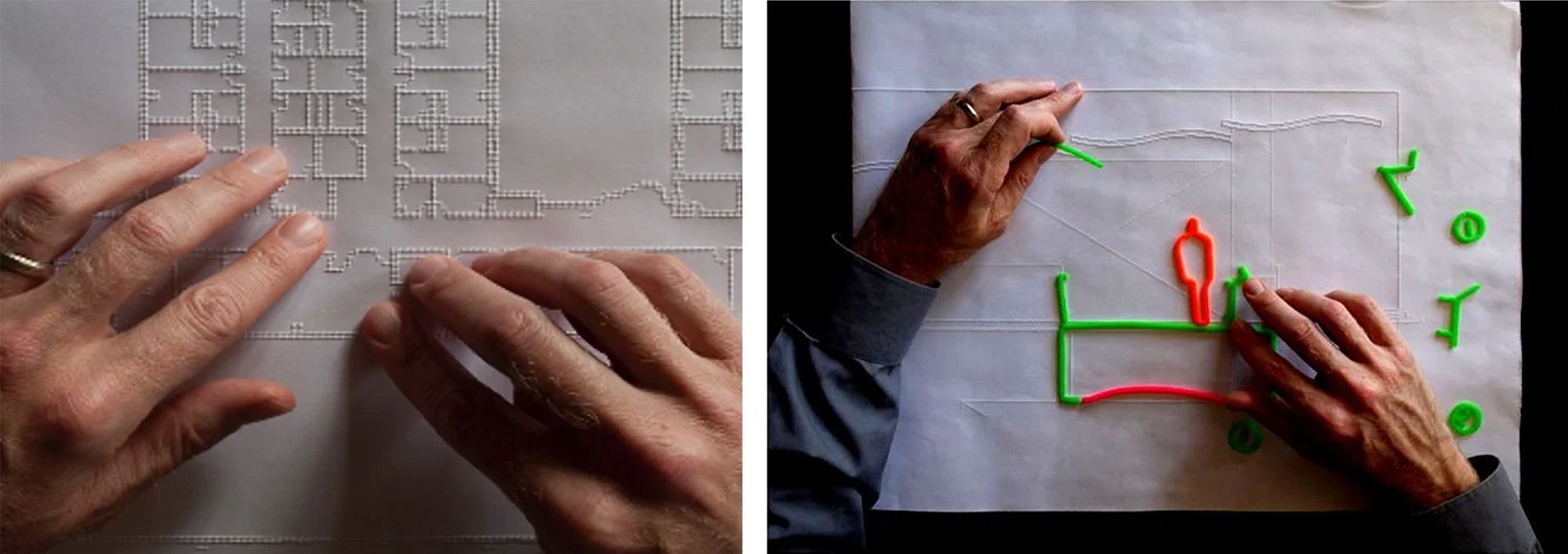

Downey found new tools for his job. He gets floor plans and elevations printed with embossed lines so he can “see” them by touch, and then uses children’s wax craft sticks to mold suggested changes on top “like a trace overlay on base drawings.”

He worked with the SoundLab at Arup, an international engineering firm, to develop an auditory design protocol where, based on a plan’s specifications for floors, walls, and ceilings, a program can generate the types of ambient soundscapes a user might experience when entering that space. Every material has its own haptic feedback, Downey noted, whether it’s brick, porcelain, rubber tile, asphalt, concrete, or carpet.

The SoundLab generates an audio demonstration of how Downey’s cane tapping the ground might sound in that space so he can make material selections and form decisions based on the most pleasing and effective acoustic experience. Material variety also helps with navigation—hardwood walkways versus carpeted seating areas, for example, or desks and counter colors that contrast sharply against flooring so those with low vision can discern where they are.

Downey has become a sought-after consultant to help design environments for the visually impaired, and he’s come to realize that his design-development tools help his clients as well as himself. He told the Perkins Eastman staff a story about one client, blind like him, who could go over embossed plans and formulate her own opinions of a proposed layout, rather than listening to someone describe it. “I was able to share them directly with her, giving her agency so she could make her own decisions and not rely on others,” he said.

Fourteen years of practicing “architecture beyond sight” thus far have underscored an imperative for Downey that his sighted peers might forget amidst the industry’s reliance on computer programs that can generate hyper-realistic plans and renderings. “It’s about designing for more than just the eye,” he said. “It’s not just your eyeballs going on a tour. They’re going there with your whole body.” That’s the approach Downey had to take at LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco—the organization that trained him to adapt when he was newly blind, and where he later served as its board president and an architectural consultant during the outfitting of its new facility on Market Street.

He helped specify a luxurious Brazilian-hardwood handrail for the organization’s central stair that extends through the heart of the three floors it occupies in its building—“molded to feel warm and welcoming in the hand and physically connect visitors to the space through touch and scale,” according to a profile in Architectural Record. Such details “convey that sense of delight, that joy of design, even when you can’t see it,” Downey said.

Downey’s overall message to designers at Perkins Eastman was that universal design—or “universal delight” as he likes to call it—goes much further than simply meeting a code to make everything accessible. As former LightHouse CEO Bryan Bashin once told him, “We don’t necessarily need more codes in regard to blindness. We just need better design.” Bashin nailed it, Downey explained. Losing your sight doesn’t mean losing your inspiration, or losing all the years of architectural training and sighted experience that are still firmly in his head. “The creative process—that’s the essence. That’s really what I wanted to remain a part of. It’s an intellectual process. It’s not a visual process. Your pencil doesn’t know what to draw—you do.”

More from Author

Perkins Eastman | Jul 23, 2024

The growing importance of cultural representation in senior living communities

Perkins Eastman architect Mwanzaa Brown reflects on the ties between architecture, interior design, and the history and heritage of a senior living community’s population.

Perkins Eastman | Jun 24, 2024

Not your grandparents’ senior living community: Redefining aging in place

Perkins Eastman’s Senior Living and Residential teams are putting a new face on home for seniors who don’t want to move away in retirement.

Perkins Eastman | Oct 20, 2023

Cracking the code of affordable housing

Perkins Eastman's affordable housing projects show how designers can help to advance the conversation of affordable housing.

Perkins Eastman | Sep 25, 2023

3 affordable housing projects that serve as social catalysts

Trish Donnally, Associate Principal, Perkins Eastman, shares insights from three transformative affordable housing projects.

Perkins Eastman | Jun 28, 2023

When office-to-residential conversion works

The cost and design challenges involved with office-to-residential conversions can be daunting; designers need to devise creative uses to fully utilize the space.

Perkins Eastman | May 25, 2023

From net zero to net positive in K-12 schools

Perkins Eastman’s pursuit of healthy, net positive schools goes beyond environmental health; it targets all who work, teach, and learn inside them.

Perkins Eastman | Jan 27, 2023

Enhancing our M.O.O.D. through augmented reality therapy rooms

Perkins Eastman’s M.O.O.D. Space aims to make mental healthcare more accessible—and mental health more achievable.

Perkins Eastman | Sep 21, 2022

Architecture that invites everyone to dance

If “diversity” is being invited to the party in education facilities, “inclusivity” is being asked to dance, writes Emily Pierson-Brown, People Culture Manager with Perkins Eastman.

Perkins Eastman | Aug 29, 2022

What does school safety mean?

The familiar headlines followed close after nineteen children and two teachers died in a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, on May 24, many of them blaming school infrastructure for the gunman’s ability to attack.