Cities across the nation are proposing tax breaks and other financial incentives for developers to help revive central business districts by converting vacant office buildings into residential and mixed-use projects. In most cases, these office-to-residential incentives are necessary to offset the other economic forces at play, DC Managing Principal Barbara Mullenex says. “Office buildings are worth more” than residential as income generators, she explains. “Generally, the highest and best use for something is office, if there’s a market for it. That’s why downtowns are filled with offices.”

“If there’s a market for it” is the operative term, however, because office districts in major cities are under stress as they’ve emptied out in the wake of the pandemic, and many building owners are defaulting on loans, according to The New York Times. “These buildings cease to be worth as much as they traditionally have been once a collapse like this occurs,” Associate Principal Christian Calleri says. But viewed through the lens of smart urbanism, he says, “it’s the best thing that can happen to American cities in the long term. Zoned business districts cease to function after 6 p.m.” Eliminating single-use zoning so people can live throughout the city, where all of its districts thrive at all times, is a “net positive,” he says.

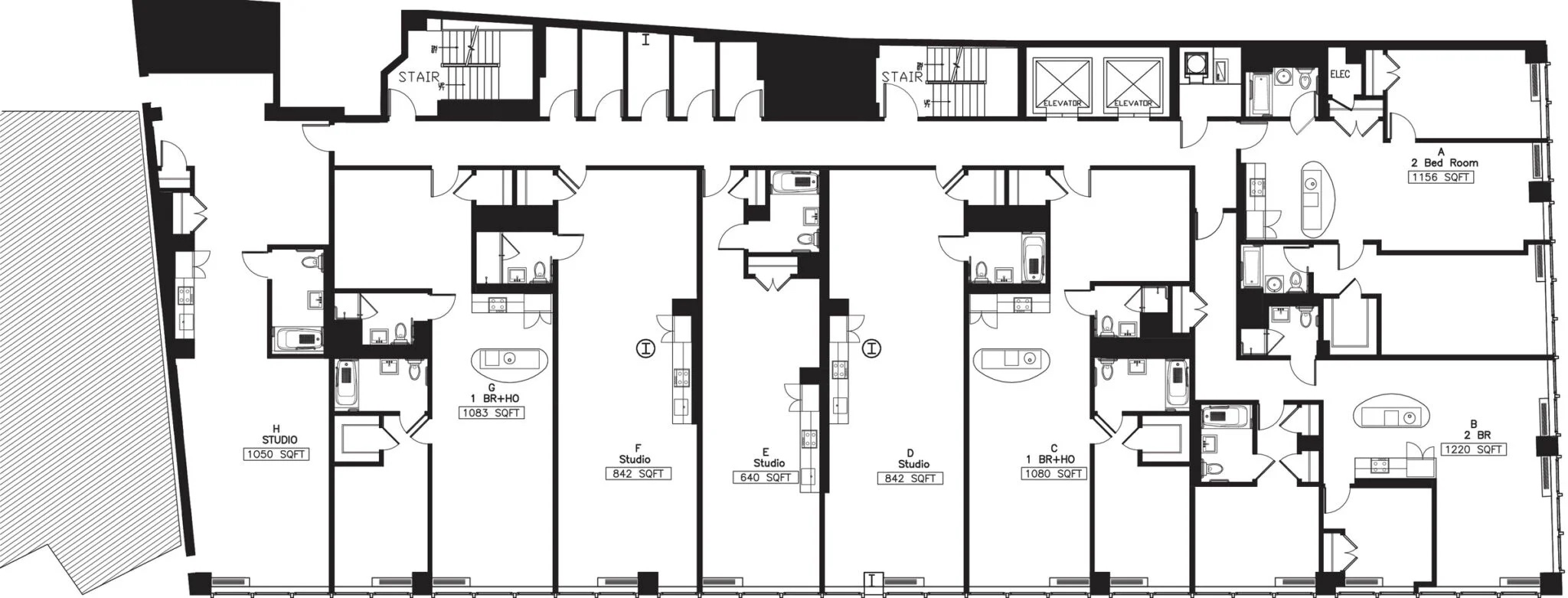

The cost and design challenges involved with conversions, however, can be daunting. Structures built since the mid-20th century generally feature large, deep floor plates whose cores are far from where natural light and fresh air could travel. This had become acceptable in office buildings in the latter half of the 20th century, but the laws governing residential buildings have “light and air” requirements mandating direct light and natural ventilation for living areas and bedrooms.

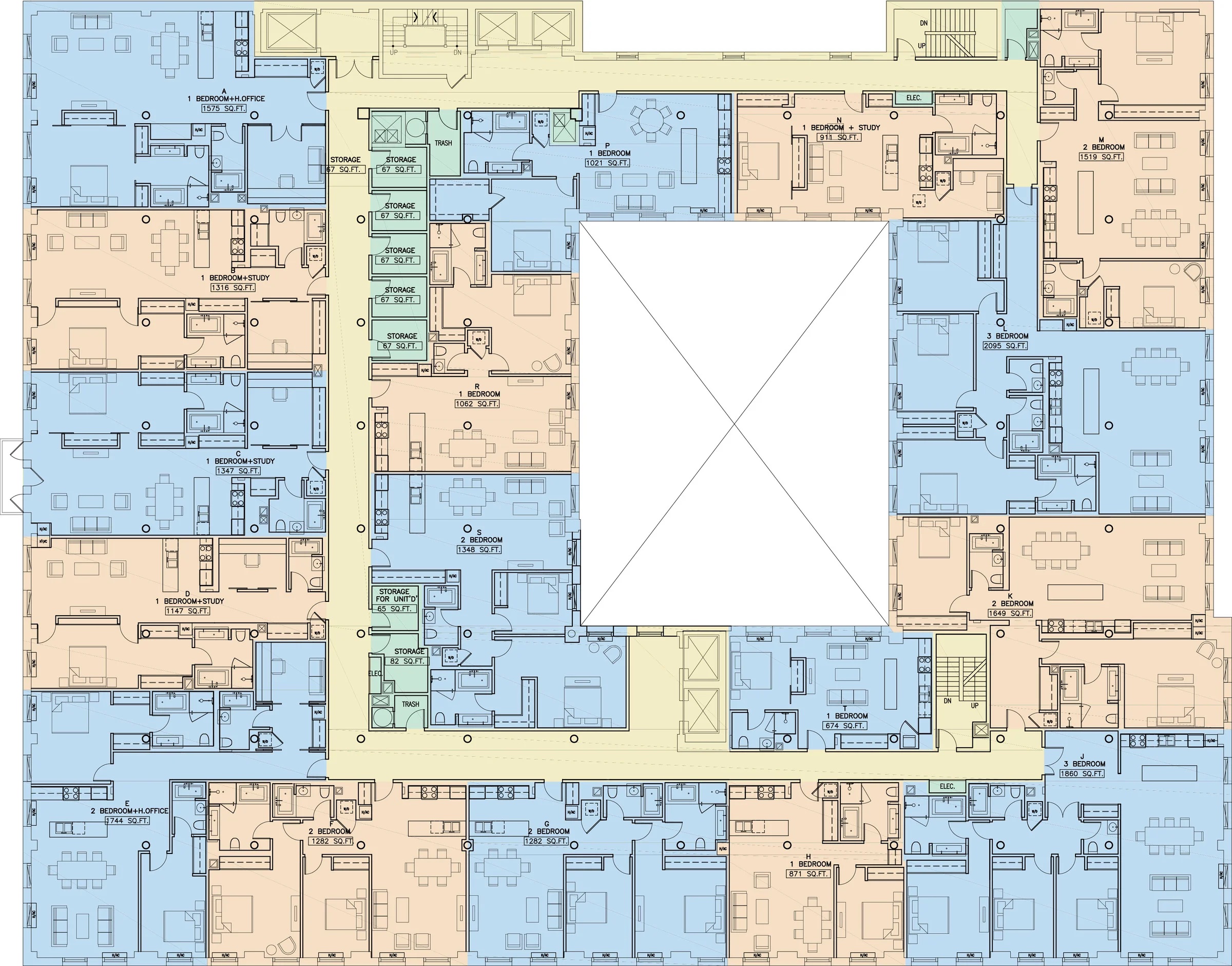

Adding to the complication is an office building’s inner core, which typically contains multiple elevators, public bathrooms, and mechanical rooms on every floor. Save for a couple of the elevators, it all needs to be repurposed for a residential conversion—and due to a lack of natural light and ventilation, designers need to devise creative uses to fully utilize the space.

Modern office buildings tend to have glass curtain walls, which typically do not have the operable windows required for residential uses, and they provide poor insulation under today’s energy-efficient standards, so developers would have to replace or retrofit them. A residential building also requires bathrooms, kitchens, and thermostats in each unit—all of which demand a massive overhaul to the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems.

“It’s not as simple as putting units in a box,” Mullenex says. Yet under the right conditions, Perkins Eastman has been helping clients achieve success. “Our track record provides insights into the numerous creative approaches we can take when it comes to converting commercial to residential,” says Perkins Eastman Associate Principal Mathew Hart,

Finding the Right Office-to-Residential Conversion

The first residents started moving into the Sinclaire on Seminary last December, populating a 212-unit apartment complex that began life as a spec-construction office building in the 1980s. The Perkins Eastman-designed conversion in Alexandria, Va., represents the ideal potential for dated commercial properties as both office vacancies and residential demands soar in urban areas across the country. And while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the flight away from offices as more hybrid and work-from-home models took hold, the pattern was already in place.

Perkins Eastman received the Sinclaire commission after its developers toured WeWork: WeLive in nearby Crystal City, Va., which inhabits a converted 1960s-era office building with co-living apartments and common workspace amenities. (WeWork: WeLive has since come under new management as the Common at National Landing.)

“It was ideally positioned,” Mullenex says, because it wasn’t in a high-rent, downtown district, it was beyond its useful life as an office, and it was in an area surrounded by other residential buildings—not to mention being close to bus and rail lines, and minutes from Reagan National Airport. “Most important,” she adds, “it was the right shape. It had the right core-to-exterior dimensions.”

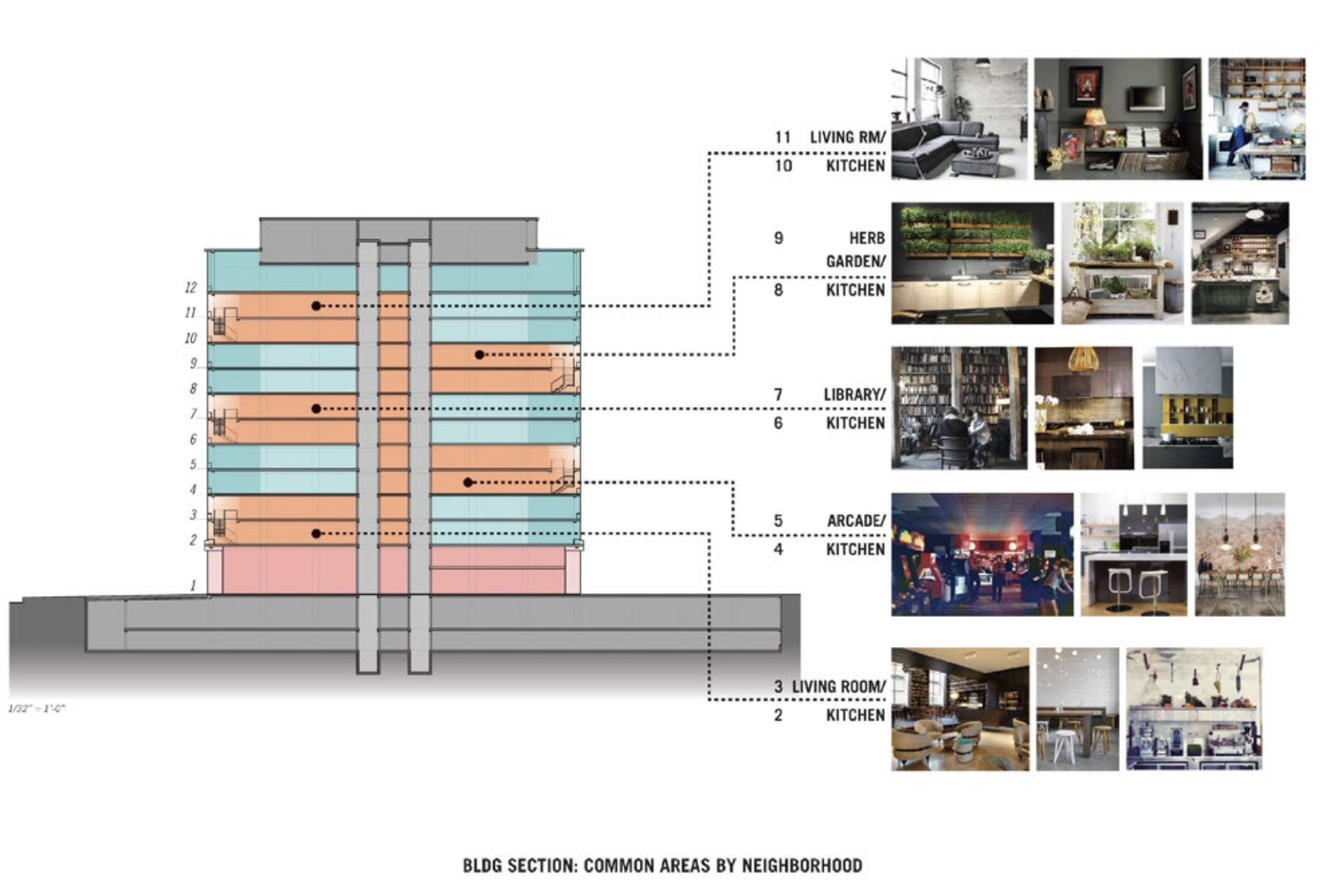

WeWork: WeLive was designed for “car-free millennials,” Associate Principal Takehiro Nakamura explains. The existing ceiling heights were relatively low compared to the nine- and 10-foot ceilings in luxury residential properties. The client wanted to keep change to a minimum, so the building was positioned at a more affordable price point. It consists of small units centered around multi-floor “neighborhoods,” connected by open, daylit stairs, that contain communal kitchens, TV lounges, and an arcade, among other features. “They had a whole new vision of how people could live,” Mullenex says, by creating community among residents via these shared amenities.

Hart and his colleagues have delivered presentations for developers exploring how to treat the problematic core space in office buildings with larger floor plates. In new construction, developers typically prefer to locate their amenities in one or two locations—the main level and rooftop, for example. But with an office-to-residential conversion, they’re looking at amenities in the center of every floor to fill the inner space they can’t allocate to apartments or condos. “There are operational challenges to having distributed amenity spaces, so one of the things we’ve done this year is develop the concept of an urban garage,” Hart says. Instead of creating a common amenity, it could be leasable space for a tenant who wants an extension of their apartment—“a man cave or she-shed,” Hart offers, or a Zoom room or maker space—anything that doesn’t require direct light and natural ventilation. Such spaces could generate more revenue than basic storage rooms, he says.

The Older, the Better

Cities such as DC, Philadelphia, and New York also have a significant share of older, prewar office buildings that were constructed before modern HVAC systems allowed acres of interior space that’s artificially lit and mechanically ventilated. These older buildings have slimmer profiles as a result, making them more amenable to residential use. That may be why Philadelphia converted more units from office to residential than any other major US city in 2020 and 2021, according to a report by RentCafé (followed by DC, with New York rounding out the top ten).

BLTa—A Perkins Eastman Studio—is among Philadelphia’s leaders in residential conversions. It helped the developer Alterra Property Group take advantage of the city’s significant tax abatements for conversions to resurrect the circa-1899 United Gas and Improvement Company building, which had more recently been occupied by the City of Philadelphia. The new, award-winning One City is a market-rate apartment building with 323 units, just one block from Philadelphia’s historic City Hall, and it opened in 2020.

“Instead of the units being deep and narrow, they’re wide and shallow, creating bright apartments with more access to daylight than a comparable new apartment building would have,” BLTa Senior Associate Nate Sunderhaus says. “These old buildings are not going to be easier” than new construction, he points out, “but they can be a little bit more conducive to apartment layouts than the big office buildings.”

The work also involved a new secondary structure over a portion of the roof that couldn’t support the load of amenity space and a large rooftop lounge with broad views across Center City. The team dismantled layers of interior fit out and security infrastructure from the previous tenants, uncovering and restoring the building’s original architectural elements that have proven to be a major draw for new residents.

Perkins Eastman was also gifted with beautiful historic architecture in New York when the firm designed a conversion at 225 Fifth Avenue—a circa 1907 building overlooking Madison Park that once was home to wholesale gift vendors, but now houses 194 luxury condominium apartments.

New York City has favorable zoning laws that encourage conversions on buildings built in or before 1961 in certain areas of the city. Conversions allow developers advantages not available under current zoning; they can convert existing floor area that exceeds the maximum otherwise permitted, provide rear yards as shallow as 10 feet in lieu of the 30 feet currently required, and create deeper apartments with interior, mechanically ventilated, and windowless rooms. “For owners, conversion presents many challenges for economic viability,” says Perkins Eastman Principal Robert Marino, who was the principal in charge for the project. “This zoning provides opportunities to create a profitable development.”

Now known as the Grand Madison, the building benefited from an existing courtyard, which Marino and his team expanded into a larger rectangle that provides light and air to the inner units. Also under city rules, they relocated the floor area eliminated by the courtyard expansion and added new penthouse apartments and additional amenities on the roof, thus greatly adding to its profitability. Because of the high cost associated with conversions, Marino notes, most in New York City are condominiums as opposed to rental apartments where there’s generally a limit on the rent tenants are willing to pay.

Addressing New Stock

The city is considering expanding the zoning allowance to include properties built more recently, Marino says, which would make it easier for developers to convert those larger, more problematic buildings. A recent Perkins Eastman study, for example, determined it wouldn’t be feasible for a developer client to transform a 50-story, 1980s office building in Long Island City into residential. Despite tall ceiling heights, dramatic views of the Manhattan skyline, and a growing neighborhood of new residential buildings around it, “what the market told us at the end of the study was that [those attractive features] couldn’t pay for the fact that the middle third of the building was underutilized,” says Principal Christopher Ernst, who conducted the study with Marino. That, and the fact that current zoning prohibits residential conversions in newer buildings with larger floor plates, making redevelopment even more challenging.

For now, Perkins Eastman continues to help clients identify properties that can still be profitable within the challenging economic parameters that conversions present. The circa-1967 building at 90 William Street is in the city’s financial district, an area where the pre-1961 zoning allowance was already expanded to include newer buildings in lower Manhattan following a glut of vacant office space that proliferated there in the 1970s and ’80s.

For that reason, Marino and his team took advantage of the attached building, where stairs and elevators could be preserved because they were on its windowless side. And because the building is fairly slim, they could stretch units in a single layer across each floor—and build new penthouse units and amenities on the top.

A March study by the commercial real estate firm CBRE reported that while multifamily housing demand has sprung back from its COVID-19 slump, office demand still lags. “But despite the perfect cocktail of multifamily/office vacancy rates, the rate of office-to-multifamily [conversions] is little changed over the past 10 years,” the report said, naming the same financial reasons Perkins Eastman leaders have cited. The Retail practice is staying busy with conversions nevertheless, having gained years of experience recognizing what makes the best return on investment. “As architects, we can design some fabulous buildings. Give us any Rubik’s Cube and we’ll solve it,” Marino says. “We can design anything. It’s just a matter of finding creative solutions to make it work financially.”

More from Author

Perkins Eastman | Jul 23, 2024

The growing importance of cultural representation in senior living communities

Perkins Eastman architect Mwanzaa Brown reflects on the ties between architecture, interior design, and the history and heritage of a senior living community’s population.

Perkins Eastman | Jun 24, 2024

Not your grandparents’ senior living community: Redefining aging in place

Perkins Eastman’s Senior Living and Residential teams are putting a new face on home for seniors who don’t want to move away in retirement.

Perkins Eastman | Oct 20, 2023

Cracking the code of affordable housing

Perkins Eastman's affordable housing projects show how designers can help to advance the conversation of affordable housing.

Perkins Eastman | Sep 25, 2023

3 affordable housing projects that serve as social catalysts

Trish Donnally, Associate Principal, Perkins Eastman, shares insights from three transformative affordable housing projects.

Perkins Eastman | May 25, 2023

From net zero to net positive in K-12 schools

Perkins Eastman’s pursuit of healthy, net positive schools goes beyond environmental health; it targets all who work, teach, and learn inside them.

Perkins Eastman | Apr 27, 2023

Blind Ambition: Insights from a blind architect on universal design

Blind architect Chris Downey shares his message to designers that universal design goes much further than simply meeting a code to make everything accessible.

Perkins Eastman | Jan 27, 2023

Enhancing our M.O.O.D. through augmented reality therapy rooms

Perkins Eastman’s M.O.O.D. Space aims to make mental healthcare more accessible—and mental health more achievable.

Perkins Eastman | Sep 21, 2022

Architecture that invites everyone to dance

If “diversity” is being invited to the party in education facilities, “inclusivity” is being asked to dance, writes Emily Pierson-Brown, People Culture Manager with Perkins Eastman.

Perkins Eastman | Aug 29, 2022

What does school safety mean?

The familiar headlines followed close after nineteen children and two teachers died in a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, on May 24, many of them blaming school infrastructure for the gunman’s ability to attack.