Throughout the world and especially in America, modern cities are operating from a mentality organized primarily around automobiles – not people. Since the introduction of Henry Ford’s automobile, the percentage of America’s population living in urban areas has jumped from 46% to upwards of 80%, global carbon emissions from fossil fuels have increased tenfold and income inequality has ballooned to an all-time high.

Therefore, it’s worth asking if there’s a better way to imagine our districts, neighborhoods and cities to reflect what we want the world of tomorrow to look like. If 20th century planning + design was defined by how we plan around the car, 21st century planning and design can be defined by how we plan around people and healthy communities. Here are five ideas as to how that could happen:

1. First, Look Beyond Our Shores

While we’re at the beginning of this journey in America, cities across Asia and Europe already demonstrate what re-envisioning cities and districts looks like. Forward-thinking mayors like Ann Hidalgo of Paris and Ada Colau of Barcelona shape their cities’ long-term thinking through movements like the 15-minute city (where all necessary day-to-day amenities and services are concentrated in walkable neighborhoods requiring fewer car trips) and superblocks (where concentrations of blocks become pedestrianized except for essential and emergency vehicles).

In Asia, ambitious commitments by cities and companies push the boundaries of car-free, human-centric planning. For example, we’re currently working with Chinese technology company Tencent on its new districtwide Net City project in Shenzhen as an urban lab for testing ideas that put people ahead of the car. The project is a tabula rasa site with one main public space and connected nodes, all centered around a pedestrian-friendly framework. While coming from a considerably different cultural, political and geographic context, there’s a lot to learn from these projects that can be applied here.

2. Make It Slightly Inconvenient (and Safer) To Drive

Convenience is a motivating factor for day-to-day choices. So if we want to pivot away from a car-dominant mentality, we need to encourage cities to make it at least slightly inconvenient to drive. And while it’s unrealistic to expect a wholesale shift away from automobiles in cities, there are a host of solutions we can explore to make it easier for people to opt for alternative modes of transportation.

For Tencent’s Net City, traffic engineers are exploring interventions such as streets with acute corners so cars can only turn certain directions, ensuring traffic routing and pacing in a way that privileges pedestrian mobility over car movement. By changing street and traffic patterns and reorganizing blocks and functions, it’s possible to repatch the city to force drivers to slow down – something that is safer for both pedestrians and those in the car. It also makes the city quieter, an added benefit.

And in Oslo, making walking, biking and public transit the more convenient transportation option has meant removing over 700 parking spots from the city’s Downtown.

Note that while we want to shift the mindset of private automobile use in metropolitan areas, we need to double down on inclusive design and ADA accessibility which offers a new opportunity when traffic congestion is reduced and the competition for the curbside seeks new activity patterns.

3. Consider the Benefits of Wide Roadways

In the U.S. we tend to veer away from wide street and road patterns that are more commonly found throughout Asia. But there’s actually a way that we can adapt this model for US cities to plan dynamic people-centered environments. For example, the Tencent Net City requires a wide roadway right-of-way to meet the current planning regulations. But micro mobility strategies are also layered side-by-side: pedestrian walkways, protected bike lanes, bus lanes and space for scooters, e-bikes and green infrastructure buffers. Designers must envision intermittent uses that flex over time to support community creation for city dwellers and small businesses.

In addition, right-of-way width of roadways preserves daylight exposure onto the streets and sidewalks and it allows the urban fabric to ventilate. These fundamental provisions date back to the public health performance of streets in history that remain paramount during the pandemic. A hot steamy summer in New York with piles of garbage bags sharing the sidewalks with people is a picture that convinces many to want to redesign street spaces. As cities densify, daylight exposure becomes a right as well. Wider streets means more ample sunshine for everyone and even the urban forest that survives all year long inhabiting the street. Even an accommodation of three more feet to expand tree and plant beds offers a more humane streetscape to offset carbon emissions in our cities.

We already see this happening in an informal way during the pandemic in both big and small cities throughout America, which have introduced outdoor seating on sidewalks, moved walkways into the street and turned medians into hangout areas. The wider roads can provide space for both temporary and tactical urbanism interventions and programming as well as more permanent adjustments. This also allows for spaces where greater intergenerational and social mixing can occur.

4. Transform Roadways to Pedestrian Ways Across Scales

Wherever possible, we should look for opportunities to transform roadways for cars into pedestrian ways that can accommodate recreation and active transportation. We’ve already seen the popularization of car-free streets, where multi-street corridors are turned into walking and biking zones.

But there is also an opportunity to look across scales – whether it’s at an individual block level or across entire districts and neighborhoods. With the Denny Substation in Seattle – a project that turns a public utility into a community park and amenity – walkability is improved with the inclusion of community space including a quarter-mile walkway lined with public artworks, a dog park and gallery space and areas for food trucks. We also see this at the district level with Dallas’ Arts District which seeks to turn one of the most notoriously car-centric cities in America into a walkable central hub for culture and recreation.

5. Expand the Pool of Stakeholders Committed to This Work

The process of reshaping cities away from 100 years of car-dominant planning and design will take a wide and committed group of stakeholders. While this work has often been led by local government, a widening group of private and corporate firms – including a number of forward-thinking companies – are taking on this work, especially at a neighborhood and district level. These initiatives are even more impactful when new industry and local government work together in tandem to imagine, fund and maintain this work. And with city budgets constricted by the ongoing pandemic, it’s going to take additional vision and commitment by the private sector to move toward this vision.

In Summary

The reprioritization of city planning to focus first on humans and later on cars is central to the values we want to see – cities with a smaller carbon footprint and lesser climate change impact, healthy cities with cleaner air, less noise pollution, more opportunities for active transportation and more inclusive and equitable cities with quality transportation access for all. The challenge and task at hand is immense but it is achievable if the collective wisdom and commitment to bring together city planners, developers, corporations and the wider design community is realized.

More from Author

NBBJ | Oct 3, 2024

4 ways AI impacts building design beyond dramatic imagery

Kristen Forward, Design Technology Futures Leader, NBBJ, shows four ways the firm is using AI to generate value for its clients.

NBBJ | Jun 13, 2024

4 ways to transform old buildings into modern assets

As cities grow, their office inventories remain largely stagnant. Yet despite changes to the market—including the impact of hybrid work—opportunities still exist. Enter: “Midlife Metamorphosis.”

NBBJ | May 10, 2024

Nature as the city: Why it’s time for a new framework to guide development

NBBJ leaders Jonathan Ward and Margaret Montgomery explore five inspirational ideas they are actively integrating into projects to ensure more healthy, natural cities.

NBBJ | Oct 18, 2023

6 ways to integrate nature into the workplace

Integrating nature into the workplace is critical to the well-being of employees, teams and organizations. Yet despite its many benefits, incorporating nature in the built environment remains a challenge.

NBBJ | May 8, 2023

3 ways computational tools empower better decision-making

NBBJ explores three opportunities for the use of computational tools in urban planning projects.

NBBJ | Jan 17, 2023

Why the auto industry is key to designing healthier, more comfortable buildings

Peter Alspach of NBBJ shares how workplaces can benefit from a few automotive industry techniques.

NBBJ | Aug 4, 2022

To reduce disease and fight climate change, design buildings that breathe

Healthy air quality in buildings improves cognitive function and combats the spread of disease, but its implications for carbon reduction are perhaps the most important benefit.

NBBJ | Feb 11, 2022

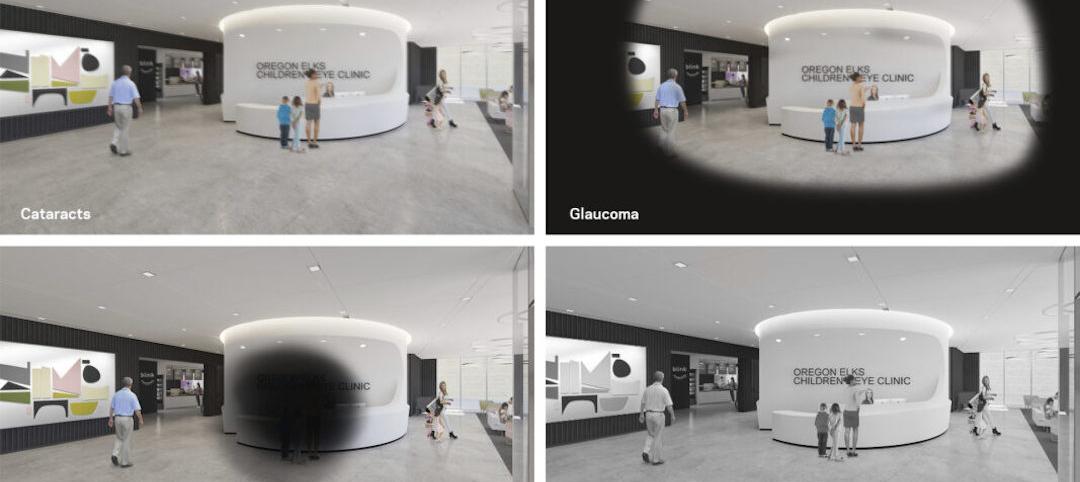

How computer simulations of vision loss create more empathetic buildings for the visually impaired

Here is a look at four challenges identified from our research and how the design responds accordingly.

NBBJ | Jan 7, 2022

Supporting hope and healing

Five research-driven design strategies for pediatric behavioral health environments.

NBBJ | Nov 23, 2021

Why vertical hospitals might be the next frontier in healthcare design

In this article, we’ll explore the opportunities and challenges of high-rise hospital design, as well as the main ideas and themes we considered when designing the new medical facility for the heart of London.