Between 100 million to 1 billion birds are estimated to die each year in the United States due to collision with glass according to the American Bird Conservancy. One third of all the bird species found in the United States have been documented as victims of these collisions.

Why do we care? Aside from the obvious—our ongoing struggle to live in harmony with nature—birds provide critical ecological functions. By consuming insects and controlling rodent populations, they reduce damage to crops and forests and help limit the transmission of diseases such as West Nile and Malaria. Birds also play an important role in regenerating habitats by pollinating plants and dispersing seeds as discussed in the American Bird Conservancy’s publication, Bird Friendly Building Design.

In the construction industry today, large expanses of glass have become common place. There’s a push for more natural daylight for occupants of buildings. The corporate sector has seen a shift to naturally-lit, open workspaces with low partitions and large expanses of glass are no longer reserved for the prestigious corner office. The education sector has also acknowledged the benefits of natural daylight on our ability to learn. Even large retail environments are incorporating skylights to allow natural light into their deep dark spaces to encourage spending. The benefits of natural daylight are obvious and undisputed.

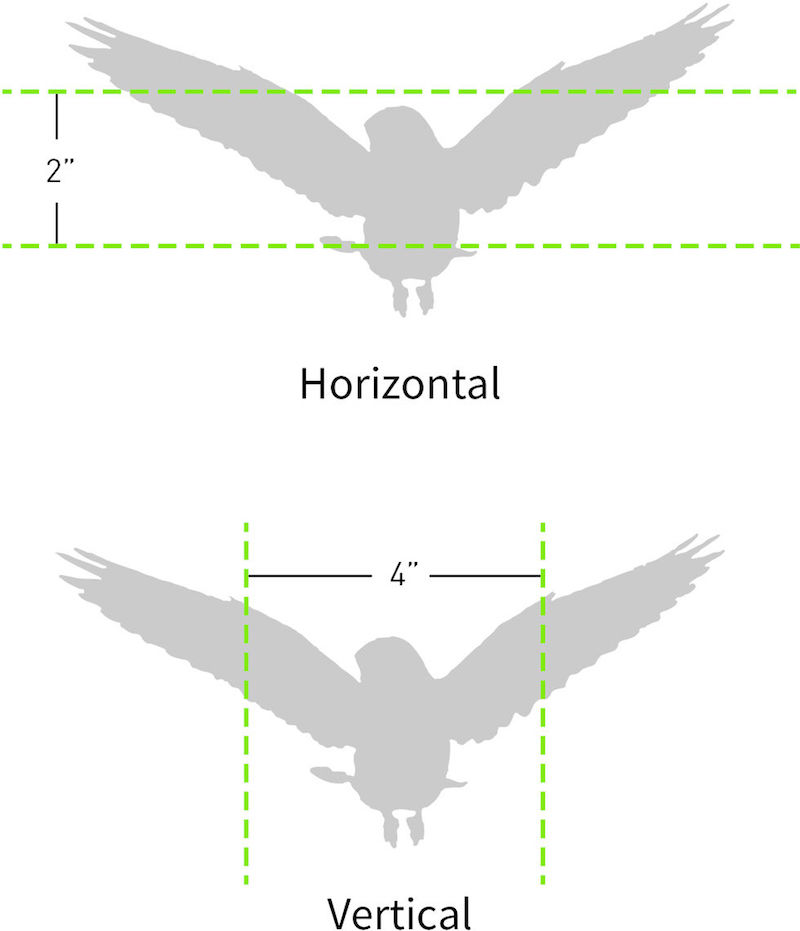

The Acopian Center for Ornithology at Muhlenberg College and The American Bird Conservancy are leading the research and testing of bird friendly glazing. Their testing has shown that most birds will not attempt to fly through horizontal spaces less than 2” high nor through vertical spaces 4” wide or less. This is widely referred to as the ‘2x4 rule.’ Research has found that patterns covering as little as 5% of the total glass surface can deter 90% of bird strikes. Stripe patterns are most common, however other patterns can be utilized if spacing is analyzed. There are several commercially available glazing products on the market that attempt to create a visible barrier to birds utilizing acid etching, ceramic frit, or UV. Patterns can be applied to glass surfaces to satisfy the 2x4 rule and create a visible barrier to birds. Research has shown that locating the pattern on the outer most surface of glass is most effective as documented by Daniel Klem in Landscape, Legal, andBiodiversity Threats that Windows Pose to Birds. This also allows for the inclusion of energy-efficient coatings to be incorporated on other glass surfaces.

In addition to specialty glass, netting, screens, grilles, or louvers, exterior shades can also be used to make glass more visible and reduce bird mortality. These solutions may offer the additional benefit of minimizing solar heat gain in a building. Overhangs, balconies, and angled glass have also been shown to minimize collisions as noted by the American Bird Conservancy.

Beyond glazing, artificial light escaping from building interiors and exterior light fixtures can attract birds. Likewise, light pollution has been known to confuse and disorient migratory birds. Using automatic lighting controls to dim or turn off lights at night can help limit light pollution, as well as save energy. Selecting exterior luminaries with low up-light ratings can minimize the amount of light pollution while also protecting migratory birds.

In particular, nature center projects often present a high risk for collisions due to building locations—typically nature preserves or parks which are home to bird populations—and the desire for glazing to connect visitors with the unique landscape and views. Responsible design of glazing can limit bird collisions and support each center’s mission.

At The Nature Place in Reading, PA, an acid-etched glazing with a horizontal stripe pattern spaced 2” apart along with sunshades was utilized to make the entire façade a visible barrier to birds. While noticeable to the human eye the pattern is minimal, thus maintaining the sweeping wetland views. Patterned glass is a premium over typical transparent glazing, however, for Berks Nature, protecting nature is part of their mission and therefore the decision to include etched glazing was easy. Bird collisions were a regular occurrence at their previous facility, but since moving into the new building one year ago, Berks Nature has not witnessed a single collision. These bird friendly design features not only support their mission, but also provide a teaching tool for visitors.

Other examples include Robinson Nature Center in Columbia, MD where glazing with a decorative leaf pattern serves as a visible barrier while also complimenting the interior living tree exhibit. Dot pattern glazing was selected for Cahill Fitness and Wellness Center, which is nestled into Baltimore’s Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park, the second largest woodland park in the US. Even at an elevation of over 14,000 feet bird collisions are a consideration. For the new visitor center atop of Pikes Peak in Colorado, in addition to bird friendly glazing featuring vertical stripes, screening has been incorporated as an integral part of the building design to both serve as a visible barrier and protect the glazing from the extreme elements.

If you need even more of an incentive, USGBC introduced a LEED pilot credit worth one point in 2011, Pilot Credit 55: Bird Collision Deterrence. The pilot credit addresses the issue of bird collision from four aspects: the façade, interior lighting, exterior lighting, and performance monitoring. The pilot credit remains available today in LEED Version 4. Proof that bird friendly design does not have to be at the cost of natural daylight and views, The Nature Place was able to achieve this pilot credit along with the Daylighting and Views Indoor Environmental Quality credits.

While legislation that promotes bird-friendly design has been enacted in some cities across America, for the most part it remains largely unregulated. Until bird-friendly design practices are required nationwide, it’s up to designers and owners to consider the avian population. Responsible design of glazing and lighting can greatly reduce deadly bird collisions and help support biodiversity in the built environment.

More from Author

GWWO | Jan 8, 2024

Achieving an ideal visitor experience with the ADROIT approach

Alan Reed, FAIA, LEED AP, shares his strategy for crafting logical, significant visitor experiences: The ADROIT approach.

GWWO | Jan 18, 2023

Building memory: Why interpretive centers matter in an era of social change

The last few years have borne witness to some of the most rapid cultural shifts in our nation’s long history. If the experience has taught us anything, it is that we must find a way to keep our history in view, while also putting it in perspective.

GWWO | Aug 17, 2022

Focusing on building envelope design and commissioning

Building envelope design is constantly evolving as new products and assemblies are developed.

GWWO | Aug 5, 2022

A time and a place: Telling American stories through architecture

As the United States enters the year 2026, it will commence celebrating a cycle of Sestercentennials, or 250th anniversaries, of historic and cultural events across the land.

GWWO | Jul 6, 2017

Achieving an ideal visitor experience: The ADROIT approach

The most meaningful experiences are created through a close collaboration between architects, landscape architects, and exhibit designers.

GWWO | Mar 1, 2017

Intuitive wayfinding: An alternate approach to signage

Intuitive wayfinding is much like navigating via waypoints—moving from point to point to point.

GWWO | Sep 6, 2016

Letting your resource take center stage: A guide to thoughtful site selection for interpretive centers

Thoughtful site selection is never about one factor, but rather a confluence of several components that ultimately present trade-offs for the owner.

GWWO | Mar 13, 2014

Do you really 'always turn right'?

The first visitor center we designed was the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center for the Everglades National Park in 1993. I remember it well for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was the ongoing dialogue we had with our retail consultant. He insisted that the gift shop be located on the right as one exited the visitor center because people “always turn right.”

GWWO | Dec 19, 2013

Mastering the art of crowd control and visitor flow in interpretive facilities

To say that visitor facility planning and design is challenging is an understatement. There are many factors that determine the success of a facility. Unfortunately, visitor flow, the way people move and how the facility accommodates those movements, isn’t always specifically considered.

GWWO | Nov 7, 2013

Fitness center design: What do higher-ed students want?

Campus fitness centers are taking their place alongside student centers, science centers, and libraries as hallmark components of a student-life experience. Here are some tips for identifying the ideal design features for your next higher-ed fitness center project.