The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance and urgency of designing learning environments to promote and protect health. Now, many are asking, what makes a healthy or health-promoting school? What defines healthy? What strategies should we target and prioritize to design healthy environments?

More than four decades of research confirms that school buildings are foundational to students’ success, affecting their health, thinking and performance. A Harvard Healthy Buildings study estimated that students will have spent more than 15,000 hours in school buildings by the time they graduate from high school. Providing a healthy environment for students may be as important as curating the appropriate curriculum to teach, the data suggests. “Research overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that a well-designed and well-maintained building supports students’ ability to learn as well as their ability to thrive,” said LPAred research manager Kimari Phillips.

In striving to achieve optimal results, it is important for designers and educators to consider how physical learning spaces impact young students’ mental well-being and physical health, especially their respiratory, nervous, endocrine and cardiovascular systems.

LPAred recently explored the existing research to focus on strategies that create real value and improve learning environments. The research provides guidance on how learning environments can promote and protect the health and well-being of all occupants throughout the life of the space.

The studies focused on a range of design and maintenance factors that influence health and performance. But three areas stood out as priorities.

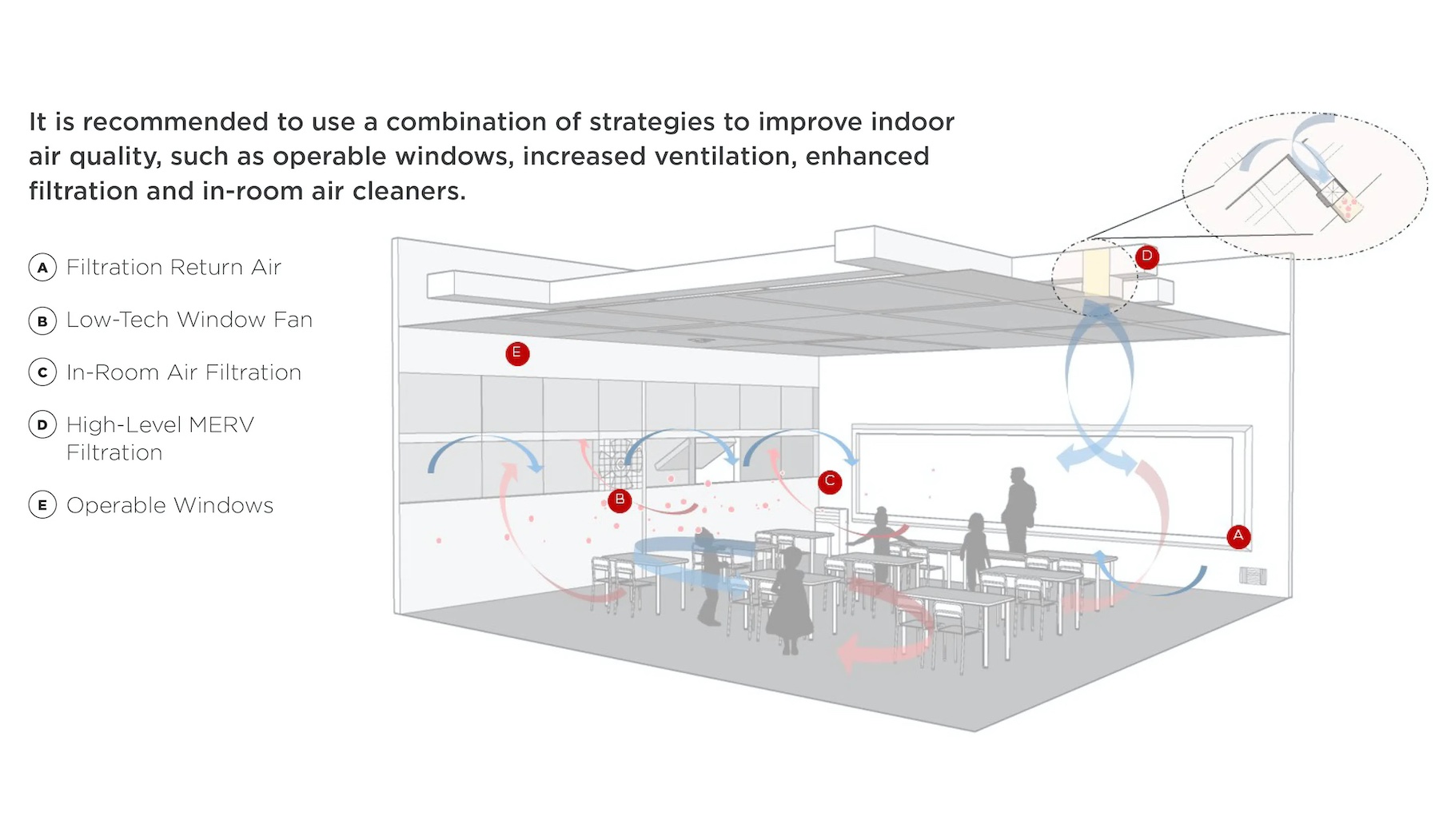

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation

According to a 2020 study, 90% of schools in the U.S. do not meet minimum ventilation standards, which can affect students’ physical health and cognitive performance. Furthermore, CO2 at certain levels begins to limit oxygen in a space, impacting occupants’ cognitive performance, awareness and reaction time. Furthermore, with high levels of CO2, occupants may also feel sleepy and have trouble concentrating. Poor ventilation can also be associated with asthma symptoms, absenteeism, reduced attention span and poorer performance on math and reading tests.

Extended exposure to breathing in particulate-matter pollution can have particularly adverse effects on people with underlying conditions, children and older adults, and such exposure is of disproportionate concern in nonwhite populations. To receive a good Air Quality Index Category rating (AQI), the safe range of PM2.5 (particulate matter) in an average of 24 hours is 12.0 micrograms or below.

A combination of strategies can improve indoor air quality. These include operable windows, increased ventilation, enhanced filtration and in-room air cleaners. Many of these strategies overlap with other healthy design strategies, such as increased natural daylight, views to nature and indoor-outdoor connection, providing further benefits to be discussed in the following section. Augmenting the number of air exchanges, ensuring the air is filtered properly, can produce measurable benefits. Additionally, displacement ventilation systems, which supply cool air at a low level, can efficiently deliver fresh air and remove contaminants.

Daylighting and Views

Proper daylighting and access to views of nature can create a positive domino effect resulting in multiple cognitive, health and well-being improvements. One study concluded that natural sunlight — also known as blue-enriched white light — enhances student alertness, concentration, cognitive processing speed and test performance. A similar report supported by the California Board for Energy Efficiency found that proper daylighting significantly improves students’ academic performance, particularly on standardized math and reading tests. Students in classrooms with the most daylighting progressed 20% faster on math tests and 26% faster on reading tests.

Higher illuminance levels in classrooms from increased access to natural daylight have also been shown to contribute to students’ health, such as improving their quality of sleep and reducing symptoms of headaches, depression, nearsightedness and eyestrain.

Lastly, designing school spaces with access to outdoor views of ample landscaping and vegetation can produce significant results relating to decreased stress and improved moods and cognitive performance. In addition to ample windows, roll-up or cantina doors, skylights, clerestories and solar tubes, as well as surface finishes that enhance natural light, can further improve access to daylight for all school occupants.

Acoustics and Noise Reduction

The acoustic environment of a space has immense influence on the ability to teach and learn. By definition, “noise” is any unwanted sound. If a classroom becomes too noisy or distracting, it is likely to lead to increased stress and fatigue in students who try to block out the unwanted sounds to hear or concentrate. Environmental noise exposure has also been linked to increased irritability, emotional symptoms, behavioral conduct problems, increased hyperactivity, higher blood pressure and lower well-being among students.

Children younger than 15 have been shown to be more sensitive to poor acoustics that fail to mitigate noise because they are still developing mature language skills. Additionally, poor acoustics in schools showed that test scores were five and a half points lower for each 10dB increase in noise level over the recommended 50dB preferred for a classroom setting.

Primary target goals for treating acoustics in classroom spaces include controlling or reducing HVAC background noise, reverberation time in the space and transmission of noise from room to room or from outside to inside the learning space. Reducing the reverberation time in spaces that have an echo or many hard surfaces involves selecting appropriate materials as well as proper maintenance of HVAC systems, since a poorly maintained system creates noisy distractions, as well as poor air quality.

References + Additional Information

Allen, et al. (2017). The 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building.

Allen & Macomber (2020). Healthy Buildings: How Indoor Spaces Drive Performance and Productivity.Eitland, et al. (2017).

Schools for Health: Foundations for Student Success. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021).

EPA Air Quality Standards - www.epa.govKeis, et al. (2014).

Influence of Blue-Enriched Classroom Lighting on Students’ Cognitive Performance. Heschong, et al. (2002).

Daylighting Impacts on Human Performance in School. Harvard C-Change (2021).

Healthy Schools.Pujol, et al. (2014).

Association Between Ambient Noise Exposure and School Performance of Children Living in an Urban Area.

More from Author

LPA | Aug 26, 2024

Windows in K-12 classrooms provide opportunities, not distractions

On a knee-jerk level, a window seems like a built-in distraction, guaranteed to promote wandering minds in any classroom or workspace. Yet, a steady stream of studies has found the opposite to be true.

LPA | May 13, 2024

S.M.A.R.T. campus combines 3 schools on one site

From the start of the design process for Santa Clara Unified School District’s new preK-12 campus, discussions moved beyond brick-and-mortar to focus on envisioning the future of education in Silicon Valley.

LPA | Mar 28, 2024

Workplace campus design philosophy: People are the new amenity

Nick Arambarri, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, NCARB, Director of Commercial, LPA, underscores the value of providing rich, human-focused environments for the return-to-office workforce.

LPA | Feb 8, 2024

LPA President Dan Heinfeld announced retirement

LPA Design Studios announced the upcoming retirement of longtime president Dan Heinfeld, who led the firm’s growth from a small, commercial development-focused architecture studio into a nation-leading integrated design practice setting new standards for performance and design excellence.

LPA | Mar 2, 2023

The next steps for a sustainable, decarbonized future

For building owners and developers, the push to net zero energy and carbon neutrality is no longer an academic discussion.

LPA | Dec 20, 2022

Designing an inspiring, net zero early childhood learning center

LPA's design for a new learning center in San Bernardino provides a model for a facility that prepares children for learning and supports the community.

LPA | Aug 22, 2022

Less bad is no longer good enough

As we enter the next phase of our fight against climate change, I am cautiously optimistic about our sustainable future and the design industry’s ability to affect what the American Institute of Architects (AIA) calls the biggest challenge of our generation.

LPA | Jul 6, 2022

The power of contextual housing development

Creating urban villages and vibrant communities starts with a better understanding of place, writes LPA's Matthew Porreca.

LPA | Mar 21, 2022

Finding the ROI for biophilic design

It takes more than big windows and a few plants to create an effective biophilic design.

LPA | Apr 28, 2021

Did the campus design work?

A post-occupancy evaluation of the eSTEM Academy provides valuable lessons for future campuses.