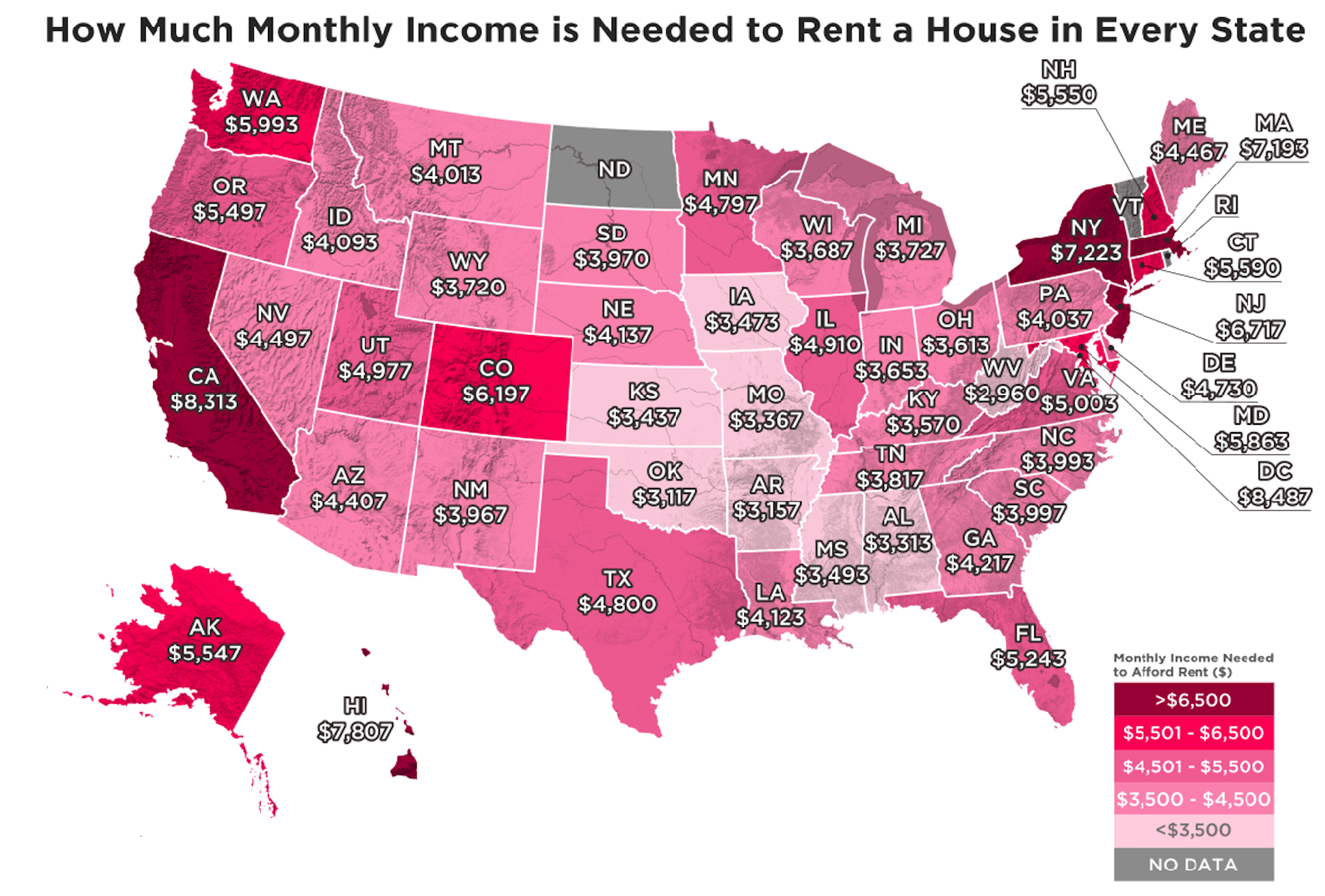

Recruitment is a growing issue for employers located in areas with a diminishing inventory of affordable housing. The world of higher education is no exception; institutions often struggle to pay staff the wages that make living near campus possible. When conversations begin with a future staff or faculty member, base pay and benefits packages are not the initial discussion. Rather, the goal is to establish the candidate’s desire to join the campus community. Giving that future employee a clear vision of how they will succeed as a part of the academic community, as well as how they can make their home within that community go hand in hand to build that desire. If they cannot find a home that supports their career near campus, they may be drawn to a more accommodating school.

At the same time, colleges and universities frequently have access to inexpensive land that they can hold for a long-term payback. They may also have the capital required to finance housing construction, or the capacity to work through private partnerships to have it built for them. They often have infrastructure in place to make housing part of a holistic solution of social and recreational amenities, or as part of a package of opportunities for employees. Housing has become a means of bridging the affordability gap, a primary marketing tool for the recruitment of valuable staff, and a way to encourage a balanced family lifestyle.

Faculty Desires: Affordability, Location, Community.

Faculty, like most of us, want to live in a neighborhood by choice, and the current trend is to live close to where they work. But the cost of housing continues to rise faster than wages, and available housing, especially in urban markets, continues to shrink while the demand increases. In many areas we are seeing an ever-increasing separation between people that can afford housing, and the remaining workforce that is pushed to the outer margins of the urban zone. That workforce is inclusive of our young professors and faculty who want an affordable place to live near their teaching and research, and desire to feel part of their community.

There is a dual necessity here: universities have a recruiting problem, and young faculty have an affordable housing problem. Institutions are feeling the need to leverage their strengths and are seeking a solution through developing housing. Typical multi-family housing projects require work and knowledge to be applied on several levels, including financial models, long range planning, construction methods and operations. Developing faculty housing also presents some unique social challenges to be addressed. Three examples are privacy, hierarchy, and community.

The Challenge: Creating Privacy, Hierarchy, and Supporting Family for Faculty within a Student-Dominated Community

The design process for staff and faculty housing must include visioning that is empathetic to their particular needs and aspirations. As this is a marketing tool for recruitment, affordability is key to helping employees begin their employment financially secure. The less they need to worry about their income covering the rent, the more they can focus on being successful in their work. However, it is also incumbent on the school to see the big picture, and develop housing where staff feel at ease and have the ability to separate their work from the rest of their life to the degree they choose.

For students, the choice to live on campus is about being part of a new social group, the support structure of the residence system, easy access to classes, and the convenience of dining halls. The desire to move off campus might include greater independence, a quieter environment, and increased privacy. For faculty, choosing to live on campus comes with the added complexity of having a home adjacent to their students and their employer. This can be a particularly strong need for faculty with partners and children.

Example: Establishing Privacy

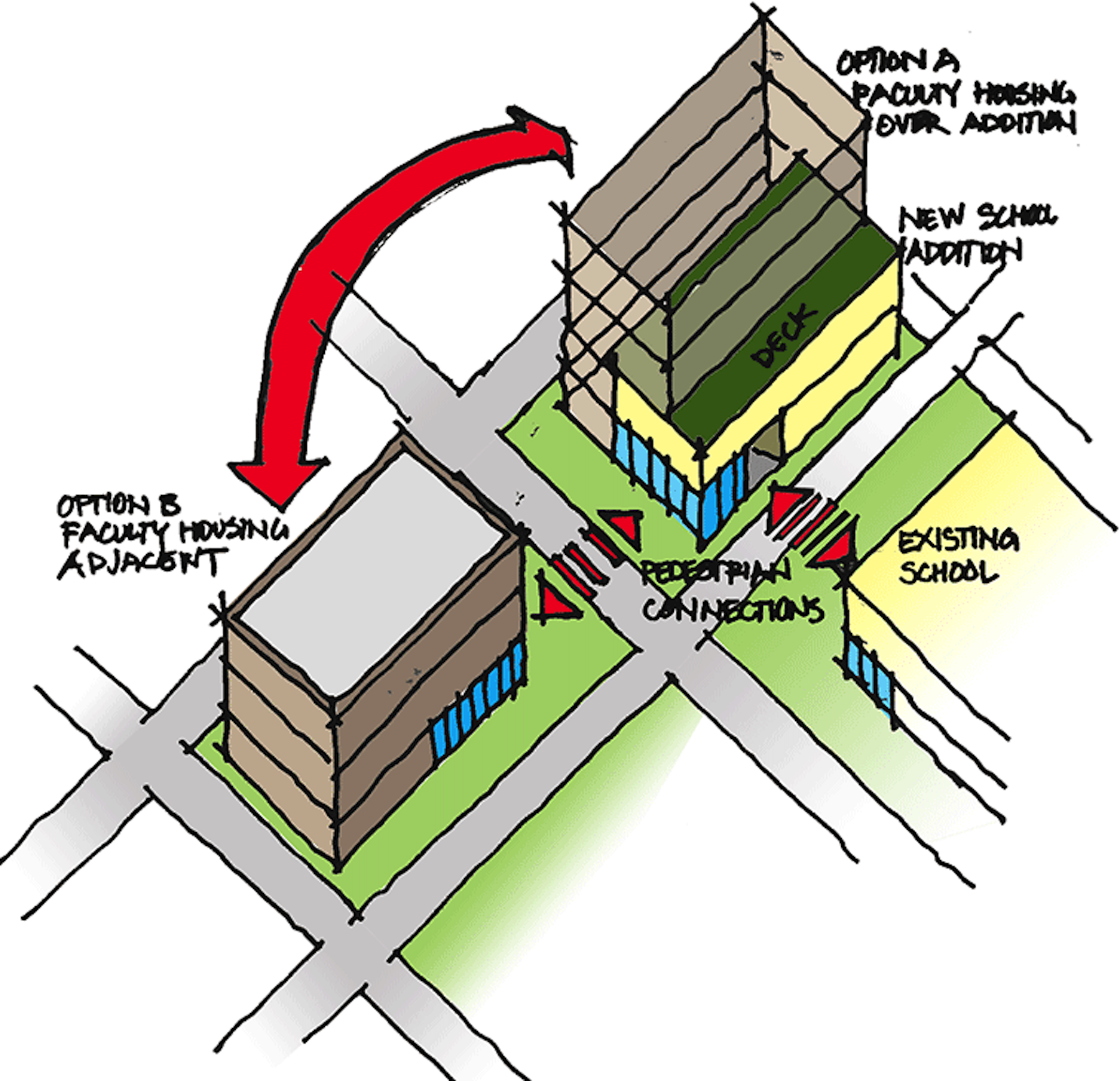

NAC is currently studying on-campus faculty housing options for a private school located on a very tight site in a transitioning urban setting. Students will be intensely activating the neighborhood throughout the day. The energy can be exciting, but it is imperative that faculty get downtime to recharge and separate from students and other staff. The first solution we studied created two buildings that divide the uses adjacent to each other on site, which also allowed for distinct fire ratings and construction sequencing. But in this case, the street presence and the cultural dynamics of the neighborhood lead us to another solution: a singular building that combines both academic programs and faculty housing. The density of the site encouraged a vertical solution, like a two-layered cake, that gave maximum expression of the school on the ground and a wholly unique building for staff above.

This separation is articulated with distinct entry points. One side of the building faces the campus and serves as the academic entrance while the more discrete faculty entrance is along a different street with an independent elevator and stair system. Amenity space is also critical to the overall design for privacy. For this project, shared amenities are limited to provide more space in each residential unit. A shared common area is available to staff and administration which can be used for scheduled private events.

Example: Creating Hierarchy

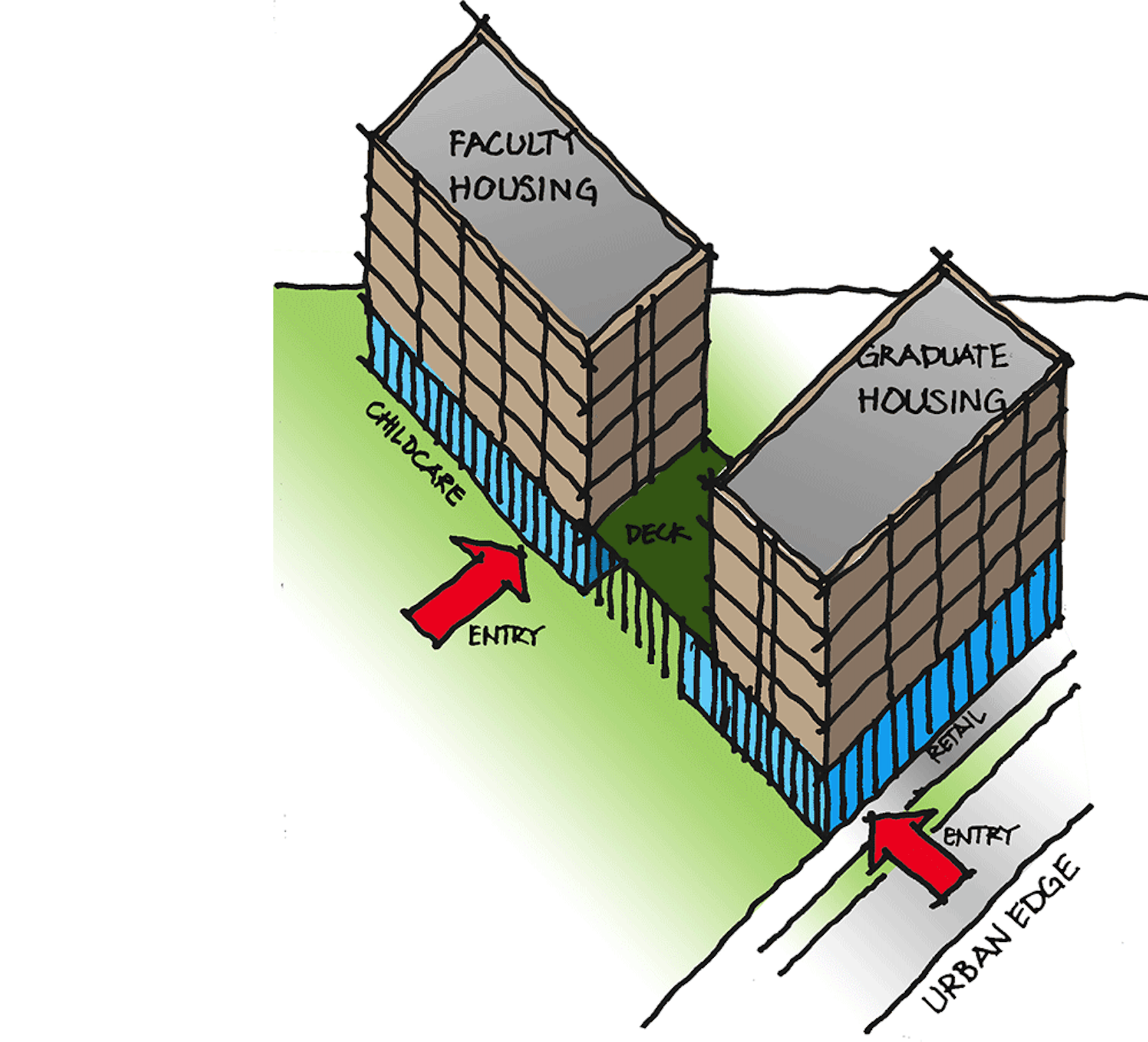

For another project, we are designing a building that combines housing for graduate students and faculty. This comes with its own issues, primarily that the close proximity in age of these residents more closely resembles a peer group than a staff/student relationship. Regardless of what level a faculty member chooses to connect with their students, they all need respite, a means of creating separation on their terms. Having the ability to set and maintain office hours, enjoy personal activities and hobbies, and to know that their home is their safe space allows them to sustain a necessary hierarchy between staff members and students.

For this project, the strategy of two separate residential buildings created the greatest ability for faculty to define their own space. Each tower has a distinct entrance, elevator system, and ground-level amenities. The graduate student building will face a quadrant of campus consisting of other student housing, a heavily utilized through-street, and contain student-focused first floor retail. The faculty building will focus on a quieter, more secluded area of campus and include a ground-floor childcare center. Additional shared amenities will create a model similar to co-working spaces, allowing faculty members to socialize, work in small groups, cook, dine, and celebrate together, creating an oasis for faculty in the midst of a vibrant campus.

Example: Supporting Family and Creating Community

At the University of Washington, an old WWII army barracks site was converted to a 400-unit faculty and graduate family housing community. The goal was to de-institutionalize the feel of the project, and emphasize family and community. The program doubled the density of apartments, and increased parking, while maintaining a family-oriented, parklike setting. All significant trees on the site were preserved, and the residences are organized into smaller neighborhoods of 30-40 homes situated around inner courtyards and green spaces. This creates safe areas for families and children to play and interact. Each neighborhood is connected by bike and pedestrian paths, and parking occurs in small “islands” interspersed around the peripheral of the site. The units themselves were designed to support faculty, graduate students, and their families equally; each features a living/dining space oriented to face the greens, with a special study loft for the students and faculty members that allow privacy from family when needed.

Conclusion

By being sympathetic to faculty needs of privacy, hierarchy, and supporting families, we can create an environment for successfully addressing the two drivers of recruitment: creating affordability and desire. While the physical approach from campus to campus may change, there are commonalities that smart planning can account for. The net result is a live, work and play environment that suits both current cultural trends, and long-standing integrated campus traditions.

More from Author

NAC Architecture | Apr 11, 2024

The just cause in behavioral health design: Make it right

NAC Architecture shares strategies for approaching behavioral health design collaboratively and thoughtfully, rather than simply applying a set of blanket rules.

NAC Architecture | Jan 26, 2023

6 ways 'choice architecture' enhances student well-being in residence halls

The environments we build and inhabit shape our lives and the choices we make. NAC Architecture's Lauren Scranton shares six strategies for enhancing well-being in residence halls.

NAC Architecture | Feb 24, 2020

Design for educational equity

Can architecture not only shape lives, but contribute to a more equitable and just society for marginalized people?

NAC Architecture | Aug 22, 2019

Holistic wellness: What we can learn from Native American healthcare practices

Are there existing organizations that have already addressed some of these issues that we can study and learn from?

NAC Architecture | Dec 7, 2018

Planning and constructing a hybrid operating room: Lessons learned

A Hybrid operating room (OR) is an OR that is outfitted with advanced imaging equipment that allows surgeons, radiologists, and other providers to use real-time images for guidance and assessment while performing complex surgeries.

NAC Architecture | Nov 7, 2018

Designing environments for memory care residents

How can architecture decrease frustration, increase the feeling of self-worth, and increase the ability to re-connect?

NAC Architecture | Oct 8, 2018

One size doesn't fit all: Student housing is not a pair of socks

While the programming and design for these buildings all kept a holistic living/learning experience at the core, they also had amazingly different outcomes.

NAC Architecture | Sep 12, 2018

Security vs. 21st century learning: We shouldn’t have to choose

In order to effectively talk about school design, we need to start by understanding what a school is designed to do.

NAC Architecture | Jul 6, 2018

Building for growth: Supporting gender-specific needs in middle school design

Today, efforts toward equity in education encompass a wide spectrum of considerations including sex, gender identity, socio-economic background, and ethnicity to name a few.

NAC Architecture | May 29, 2018

Will telemedicine change the face of healthcare architecture?

Telemedicine is a broad term that covers many aspects and mediums of care, but primarily it refers to the use of video monitors to allow a virtual face to face consultation to take place.