As economically booming cities such as Boston, New York, San Francisco and London struggle with housing their growing populations, there is an increasing fixation on the micro-unit in the name of increasing residential provision. Also referred to as the compact unit, architects and developers are bringing ingenuity and investment to creating spaces that have pared domestic life down to its minimalist essentials. These small units have catalyzed a new relationship with the public realm.

Looking to Europe one can see a long tradition of using the city as one’s living and dining room, where urban middle-income units are small in relation to North American dwellings. In the United States, however, it is relatively recent that Americans are choosing to live in city centers. Part of the appeal of the suburbs was the generous indoor and outdoor private space. The move downtown, where the offer is generally a smaller dwelling, has meant less private space. And so our new city dwellers are venturing out of their homes to pursue their social lives. This is good for our cities. This is good for our local economies.

But who are these micro-units for? On the face of it this “progress” is meant to help address both the accommodation of sheer numbers of people and the affordability of living in the city. However, it is impossible not to question how tiny units truly answer this need.

It has become apparent that we are creating city centers that cater to a thin slice of the population: pre-nesters and empty-nesters. The problem is threefold: the units being built are, even if not micro, rarely larger than 2-bedrooms (and a tight 2-bedroom at that); secondly, only a very small percentage are “affordable,” not to mention that the definition of “affordable” means many lower-middle-income people do not qualify for support; and, thirdly, the city’s amenities and services are often unaffordable as they cater to the affluence of those who can afford the newly built units.

It has become apparent that we are creating city centers that cater to a thin slice of the population: pre-nesters and empty-nesters.

For the millennials currently sharing a dwelling unit, they are forced out of the urban center to the suburbs when they want to have families. Even if housing and services affordability is not the barrier, there are few homes catering to households requiring 3-bedrooms or more. People are left little choice but to join the swathes of commuters emitting carbon, undoubtedly against their better judgement.

There is a further related concern. Thanks to policy and design guidance, many condominium buildings are designed to accommodate retail or food & beverage on the ground floor. However, despite the fact that people may be looking to the city to fulfill their entertainment needs, we find increasing numbers of empty shopfronts on our main streets and city centers. In this era of on-line shopping and food delivery, it is acutely obvious that we can no longer rely only on shops, cafes, bars and restaurants to activate our streets. Meanwhile, competing for market share, developers provide their condo buildings with gyms, meeting spaces, makers’ spaces and indoor dog runs. It is time these amenities are literally brought down to the ground. Let’s redistribute the activity.

As learning and making become more widely accessible and less institutionalized, one can imagine these sorts of uses occupying ground floors and attracting public interaction. Boston’s downtown was boosted when Suffolk and Emerson Universities came to occupy both bespoke and existing buildings. As students do not lead a nine-to-five lifestyle, ground floor activity and “eyes on the street” have improved round-the-clock.

Similarly the contemporary public library can become a space that projects and attracts vibrancy. The Idea Store in London is a good example of this. Community infrastructure — from gathering space to recreation to cultural events — provides clues as to the sorts of uses that co-exist well with the public realm. This may call for revisions to existing zoning to allow for diverse ground-floor uses — indeed, redefining “active frontage.”

The concept of the Business Improvement District (BID) has been a fantastic mechanism in many city centers, improving the safety, cleanliness and temporary events in many downtowns. However, it may also be time to redefine the scope of the BID, enforcing ground-floor activity even if that means providing space to a tenant that is not a commercial enterprise, such as a cultural institution or community use. Positive, or negative, incentives to lease empty shopfronts may be required.

It is time to promote — even demand — building types that accommodate larger households and instigate mechanisms that facilitate the distribution of amenities and services across the scale of not just a building but an urban block or blocks. This entails exploiting the trend to blur the distinction between dwelling, working, leisure and learning. In this way those people living in micro-units — as it is unrealistic, nor even desirable, that they all disappear — as well as larger multi-generation households, will have a more interesting city to venture into.

More from Author

NBBJ | Oct 3, 2024

4 ways AI impacts building design beyond dramatic imagery

Kristen Forward, Design Technology Futures Leader, NBBJ, shows four ways the firm is using AI to generate value for its clients.

NBBJ | Jun 13, 2024

4 ways to transform old buildings into modern assets

As cities grow, their office inventories remain largely stagnant. Yet despite changes to the market—including the impact of hybrid work—opportunities still exist. Enter: “Midlife Metamorphosis.”

NBBJ | May 10, 2024

Nature as the city: Why it’s time for a new framework to guide development

NBBJ leaders Jonathan Ward and Margaret Montgomery explore five inspirational ideas they are actively integrating into projects to ensure more healthy, natural cities.

NBBJ | Oct 18, 2023

6 ways to integrate nature into the workplace

Integrating nature into the workplace is critical to the well-being of employees, teams and organizations. Yet despite its many benefits, incorporating nature in the built environment remains a challenge.

NBBJ | May 8, 2023

3 ways computational tools empower better decision-making

NBBJ explores three opportunities for the use of computational tools in urban planning projects.

NBBJ | Jan 17, 2023

Why the auto industry is key to designing healthier, more comfortable buildings

Peter Alspach of NBBJ shares how workplaces can benefit from a few automotive industry techniques.

NBBJ | Aug 4, 2022

To reduce disease and fight climate change, design buildings that breathe

Healthy air quality in buildings improves cognitive function and combats the spread of disease, but its implications for carbon reduction are perhaps the most important benefit.

NBBJ | Feb 11, 2022

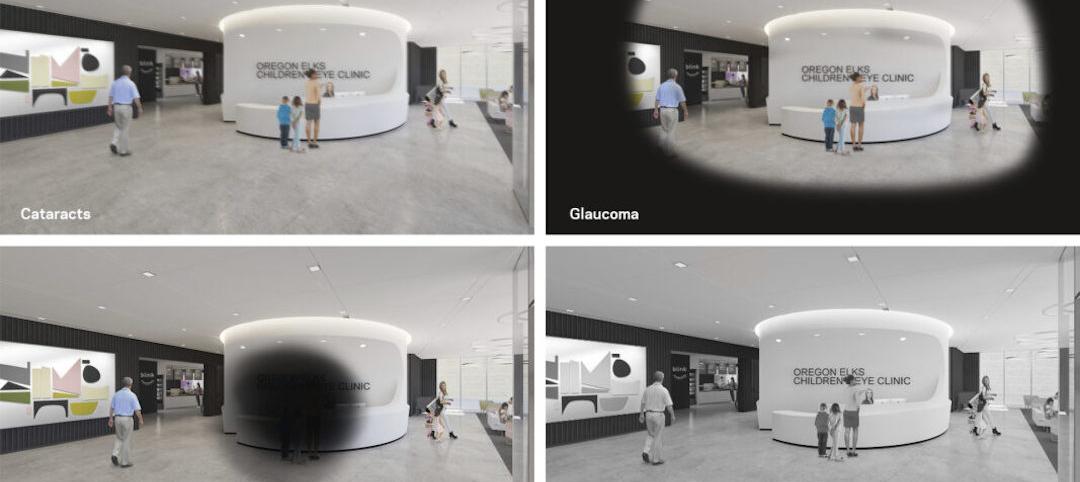

How computer simulations of vision loss create more empathetic buildings for the visually impaired

Here is a look at four challenges identified from our research and how the design responds accordingly.

NBBJ | Jan 7, 2022

Supporting hope and healing

Five research-driven design strategies for pediatric behavioral health environments.

NBBJ | Nov 23, 2021

Why vertical hospitals might be the next frontier in healthcare design

In this article, we’ll explore the opportunities and challenges of high-rise hospital design, as well as the main ideas and themes we considered when designing the new medical facility for the heart of London.