The use of third parties to develop and own new medical real estate projects is increasingly viewed as an attractive option for health systems seeking ways to preserve and generate precious capital resources to fund acute care programs and market share growth. The right third-party developer can help health systems create medical facilities with market-competitive rental rates as well as provide several benefits, such as future flexibility for the hospital, avoidance of the legal exposure that may come with serving as a landlord to referring physicians, and a potential investment vehicle for physician-tenants.

However, the selection of a developer for a new project can create challenges for health system executives. To obtain the most competitive terms, hospitals usually issue a request for proposal (RFP) as part of the selection process. In addition to the time and effort dedicated to developing and managing the RFP, hospitals also may face challenges in keeping pace with the changing economics of the real estate development industry.

One of the biggest challenges health systems face when issuing a RFP is in maintaining maximum negotiating leverage for as long as possible when selecting a developer for a new project. Three critical steps can enhance the negotiating leverage of health systems when managing the developer selection process: understanding the risk-return profile of the equity backing the developer, establishing confidence in the developer's ability to achieve target value design, and diligently vetting all legal documentation associated with the project.

UNDERSTANDING THE EQUITY

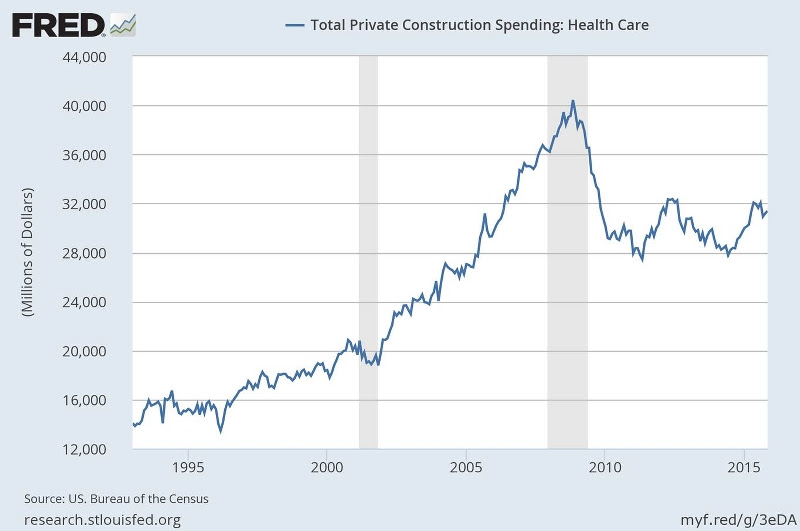

A health system increases its likelihood of negotiating the best terms for a new project by understanding the dynamic of the equity source behind a developer. Although the demand for healthcare development projects among equity sources has significantly increased in recent years, the number of opportunities to place the equity remains below prerecession levels. The healthcare development market peaked in 2008 with $40.4 billion in private U.S. healthcare construction spending, and it remains 23 percent below that, at $31 billion, as of November 2015.

Total Private Construction Spending: Health Care

Total Private Construction Spending: Health Care

In a market with limited opportunities to place capital, low interest rates, and an abundance of debt and equity that is pursuing healthcare real estate, developer yields continue to compress for the most competitive projects, to the point that healthcare developers are much less likely to fund new projects through investment from "friends and family." Instead, developers looking to compete are seeking the most aggressive sources of capital, which typically take the form of equity from pension funds and publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs).

Although pension funds have the lowest cost of capital in today's market, their commitments to new projects are closely tied to the geographic location of the project and the credit of the health system. The most active state pension funds with allocations to healthcare real estate, usually advised through investment managers, include those in Alaska, Arizona, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Wisconsin and

Texas. As public pensions shift their asset allocation toward the "endowment model," which historically has had higher allocations in alternative assets, we expect this capital source to correspondingly increase allocations to commercial real estate. Pension funds are primarily seeking real estate development opportunities, including through health systems that are in primary and secondary markets with backing by investment-grade credit. Although pension funds may have very specific criteria, they typically are able to offer greater flexibility regarding forward equity commitments, ground lease structuring, and purchase options by the hospital sponsor, and ownership models for physician tenants.

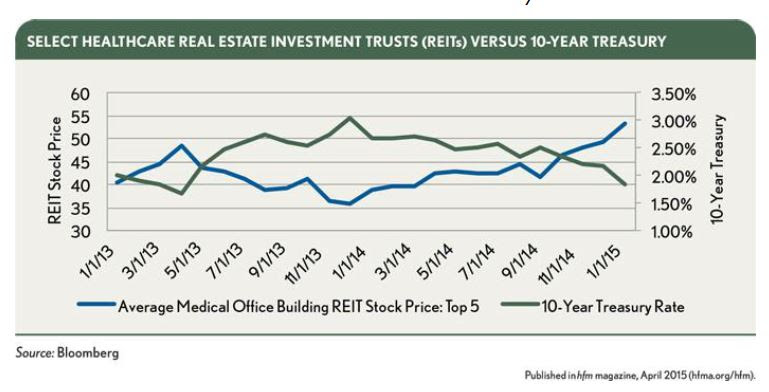

Although public REITs have less flexibility than pension fund equity, they typically offer longer term stability. REITs, as an asset class, generally do not sell their owned facilities because each asset in their portfolio provides rental income that supports the payout of dividends to their shareholders. As a potentially infinite holder of real estate, REITs historically have served as a preferred equity source for health systems. However, REITs are more interest-rate sensitive than any other equity source for developers, and generally are unable to offer a fixed forward equity commitment more than 12 months in advance for any project. REIT stock prices tend to move counter to fixed-income interest rates, such as the 10-year Treasury note. As interest rates decrease, stock prices for REITs tend to increase because they pay investor dividends, which typically float between 4 and 5 percent. Investors faced with rising interest rates tend to move away from dividend-generating stocks and toward options with higher yields.

Select Healthcare REITs Versus 10-Year Treasury

Select Healthcare REITs Versus 10-Year Treasury

BALANCING COSTS WITH DESIGN

During the developer proposal selection process, health systems should beware that the lowest yield does not always produce the lowest lease rate. Health systems typically emphasize the lease constant or developer yield, but pay less attention to the other variables in the equation, such as the cost of construction or miscellaneous fees.

A key question health systems should ask is whether the developer is experienced in achieving target value design (TVD) while delivering a state-of-the art facility. TVD delivers value to the health system through the design process while recognizing the importance of constraints such as construction costs. TVD was a target-costing practice popularized in Japan during the economically turbulent 1990s to create high-quality, cost-efficient facilities. The process aims to push the developer, architect, and general contractor to excel and innovate through the exclusion of standard approaches to design and construction. The use of financial targets and consideration of the expected value to the health system can drive creativity and problem solving. Developers often do not select their architect or general contractor before submitting their proposal to ensure that the hospital helps in the selection process for those positions and supports them. Hospitals can enhance their standard role in the selection process by reviewing a short list of the developer's proposed architects and general contractors to help gauge their historical success in achieving TVD.

As part of the selection process, health systems can go beyond simply analyzing the developer's fee by comparing miscellaneous fees, such as those for feasibility studies, project management, leasing, and financing. When miscellaneous fees surface after the developer is selected, the overall budget is increased, leaving the health system to ultimately grapple with a higher rental rate.

INVOLVING LEGAL EXPERTISE EARLY

Before beginning the developer selection process, health systems should determine their priorities. A memorandum of understanding should clearly state preferences regarding issues such as future options to purchase the facility, rights of first refusal to lease the space, specific ground-lease control provisions, and physician ownership models. The health system should share this document with the short list of developers in the final round of the selection process, and should request redline comments from the developer's legal counsel. At this point in the selection process, the involved parties generally are provided with key legal documents, such as the developer agreement, ground lease (if applicable), and space lease, to make a final selection. Although the developer may formally present the proposal, the legal documents often are provided for comment to the equity source backing the developer. A critical step is for the health system to review redline comments while it still has leverage, to bolster its negotiating position if the equity source responds with any comments that conflict with the health system's goals.

CONCLUSION

By running a detailed and competitive process from the beginning while in a position of leverage, a health system can benefit from a more streamlined process and from minimized risk after selecting a developer for a new project.

Footnote

a. Lease Constant: The developer and tenant agree on a factor (called a lease constant or developer yield) to be multiplied by the total development cost of the project to determine the initial annual rent. For example, if the lease constant/developer yield is 9 percent and the project cost for a 75,000-square-foot medical office building is $20 million, then the initial rent would be $1.8 million, or $24 per square foot.

About the Author: Chris Bodnar joined CBRE in 2003 and is an Executive Vice President of the Investment Properties division and co-leads the CBRE Healthcare Capital Markets Group with his business partner Lee Asher. Disciplined in the specialty of Investment Sales, Mr. Bodnar has been involved in the disposition of over 10 million square feet of commercial assets, exceeding a total value of $3 billion dollars on behalf of his clients since 2010.

Related Stories

| Oct 30, 2014

CannonDesign releases guide for specifying flooring in healthcare settings

The new report, "Flooring Applications in Healthcare Settings," compares and contrasts different flooring types in the context of parameters such as health and safety impact, design and operational issues, environmental considerations, economics, and product options.

| Oct 30, 2014

Perkins Eastman and Lee, Burkhart, Liu to merge practices

The merger will significantly build upon the established practices—particularly healthcare—of both firms and diversify their combined expertise, particularly on the West Coast.

| Oct 21, 2014

Passive House concept gains momentum in apartment design

Passive House, an ultra-efficient building standard that originated in Germany, has been used for single-family homes since its inception in 1990. Only recently has the concept made its way into the U.S. commercial buildings market.

| Oct 21, 2014

Hartford Hospital plans $150 million expansion for Bone and Joint Institute

The bright-white structures will feature a curvilinear form, mimicking bones and ligament.

| Oct 16, 2014

Perkins+Will white paper examines alternatives to flame retardant building materials

The white paper includes a list of 193 flame retardants, including 29 discovered in building and household products, 50 found in the indoor environment, and 33 in human blood, milk, and tissues.

| Oct 15, 2014

Harvard launches ‘design-centric’ center for green buildings and cities

The impetus behind Harvard's Center for Green Buildings and Cities is what the design school’s dean, Mohsen Mostafavi, describes as a “rapidly urbanizing global economy,” in which cities are building new structures “on a massive scale.”

| Oct 13, 2014

Debunking the 5 myths of health data and sustainable design

The path to more extensive use of health data in green building is blocked by certain myths that have to be debunked before such data can be successfully incorporated into the project delivery process.

| Oct 12, 2014

AIA 2030 commitment: Five years on, are we any closer to net-zero?

This year marks the fifth anniversary of the American Institute of Architects’ effort to have architecture firms voluntarily pledge net-zero energy design for all their buildings by 2030.

| Oct 8, 2014

Massive ‘healthcare village’ in Nevada touted as world’s largest healthcare project

The $1.2 billion Union Village project is expected to create 12,000 permanent jobs when completed by 2024.

| Oct 3, 2014

Designing for women's health: Helping patients survive and thrive

In their quest for total wellness, women today are more savvy healthcare consumers than ever before. They expect personalized, top-notch clinical care with seamless coordination at a reasonable cost, and in a convenient location. Is that too much to ask?