Like many design firms, DLR Group is working throughout North America, Asia, and Africa on large-scale projects to address the needs and pressures of urbanization. While we focus on designing organized and supportive architecture, much of urbanization is created through informal settlements: 90 percent of urbanization currently occurs in the developing world. In Africa, the urban population is expected to rise from 400 million to 1.2 billion in the next 30 years; and more than 60 percent of the current population lives in informal settlements.

This growth is creating a need for complex developments that accommodate demographics on opposite ends of the spectrum. Developments designed to account for lower income activities can help to avoid informal settlements that give rise to weak—and even dangerous—structures, and where fresh water and proper sanitation are only a faint shadow of what they should be.

When we evaluate a new project opportunity, and measure our investment of time and focus, there are a series of questions that we ask. Some are questions anyone investing in the project would ask, while others are related to urban and regional planning concerns. The most fundamental question one can ask for a new city project is: What does this location offer as a catalyst for a city? Historically, cities that develop organically tend to be at some type of crossroads or natural resource. They have a purpose, and a location, that make sense. In Africa and the American west, some of these cities formed during the construction of a railroad system that required supply depots every few hundred miles. Nairobi is an example of this driver of development. It was created as a supply depot for construction of the Uganda Railway, and the location was selected for its water supply, being roughly halfway between the port of Mombasa and Ugandan capital of Kampala.

Having a large piece of vacant land is not enough to make a place: Developers need a location with natural advantages. That singular feature can be the focus of a design around which that city operates as if it grew organically, because it is working with rather than againstthe natural forces around it.

Building Local Communities

I have visited a few informal settlements and have seen people displaced for high-value development. On a trip to Mumbai I visited a recent project that included a shiny new skyscraper and a series of very cheap five-to-seven-story walkups to rehouse previous inhabitants of the site. While this approach is better than outright displacement, it falls far short of sustaining the local community. To their credit, these new buildings provide critical sanitary infrastructure that is lacking in self-built communities, but they are soulless storage facilities for people. Self-built communities evolve, as any developed city, out of a set of organic rules that create natural boundaries for retail and residential zones, and reflect the scales of community that make a place and its people successful. Re-housing forces a great trade-off of infrastructure versus community. It would be a quantum leap forward to make both available at the same time.

As a counter point to the Mumbai approach, one of our projects in East Africa is a new city driven by the creation of a new seaport. Many of the tens of thousands of people who will move here to get employment will not all be able to afford developer built apartments. To this end, we are designing serviced plots that have the requisite infrastructure, but will allow residents to self-build their accommodations.

The success of new cities can also hinge on the approach to construction with an eye to building a local economy and skill base. A few years ago I visited a new city being developed in the West Bank, Rawabi. It is being used by the developer as a way of contributing to the long-term employment market rather than just during construction, by funding local entrepreneurs to create businesses that can serve the local construction market at large. One example is the creation of a window company, so that these large components can be built in Palestine rather than being imported.

We are also employing this technique in our work in Africa. For instance, in Mombasa, Kenya, we are building a mixed-use town center where the structures will be built from locally-quarried concrete and locally quarried petrified-coral for cladding. The office building in this development will be naturally ventilated so an all-encompassing solar shading system is required. The sun comes from all four sides in Kenya, so we are not importing a European brise soliel that would take money out of the country. Instead, we have designed a collection of smaller screens that can all be built by artisans from the neighborhood. Our general contractor will build the frame for all these screens as a sort of patchwork quilt that will become a legacy for the local community. This approach keeps foreign investment on site, rather than exporting it back to the country from which it came. It also eliminates unnecessary transport miles from the supply chain, thereby reducing our carbon footprint.

Wherever We Work

Working in locations with a pronounced divide between rich and poor teaches us about the issues that we need to grapple with, but these issues exist everywhere. In Seattle or Los Angeles, for example, a growing homeless population has created tent cities and RV neighborhoods. Just like in Africa, these are informal settlements, too. We need to abandon any sense of an inevitable Faustian bargain and identify opportunities to improve all aspects of the human experience through design.

Related Stories

Sustainability | Jan 30, 2019

Denmark to build nine industrial, energy-producing islands surrounded by a ‘nature belt’

The project will be located 10 km (6.2 miles) south of Copenhagen.

Urban Planning | Jan 25, 2019

Times are changing, and sustainable cities are taking notice

Two recent studies by Pew Research Center and WalletHub shined a light on where we are in the market transformation curve for environmentalism and sustainability.

Urban Planning | Oct 11, 2018

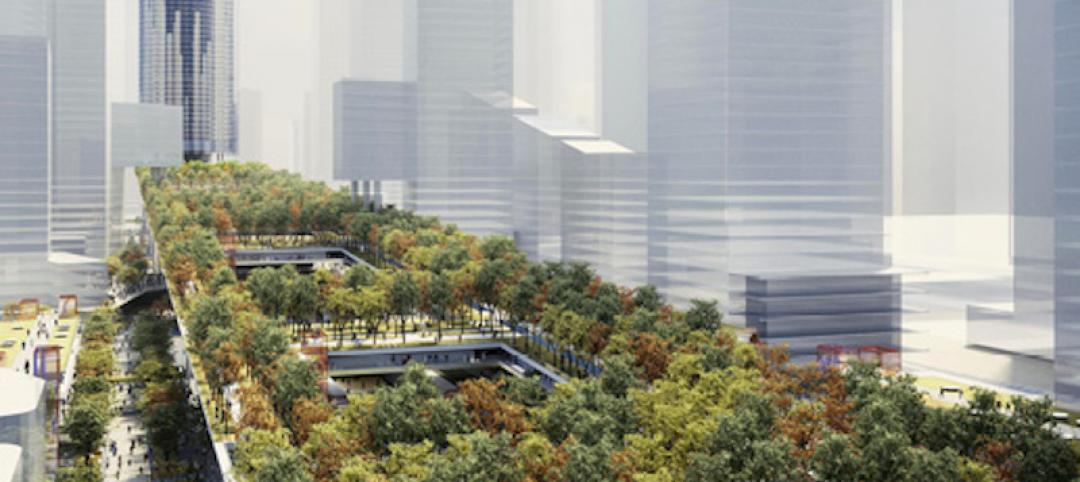

Shenzhen’s new ‘urban living room’

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners is designing the project.

Urban Planning | Sep 11, 2018

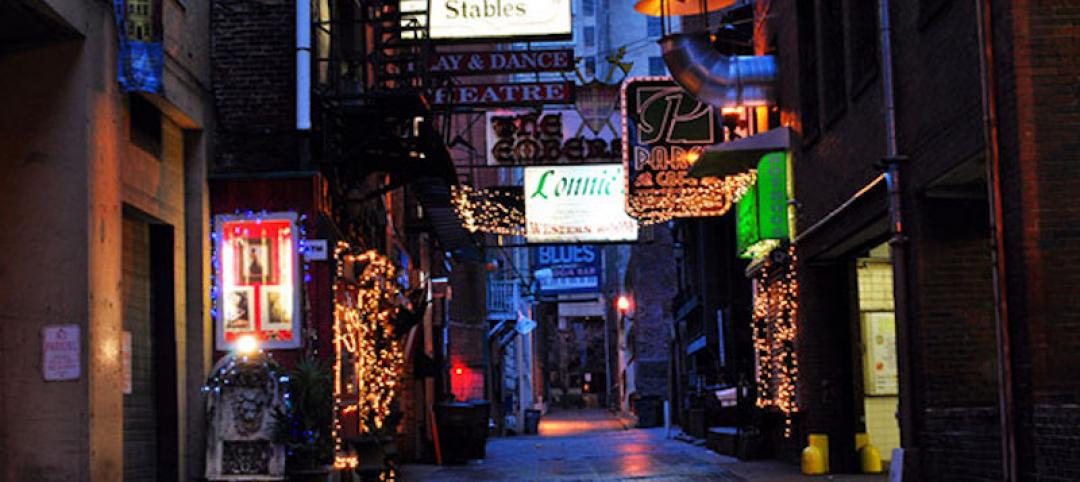

The advantages of alleys

Believe it or not, alleys started off as public spaces.

Urban Planning | Jul 24, 2018

Deregulation for denser development in Los Angeles moves forward

The aim is to reduce housing costs, traffic congestion.

Urban Planning | Jul 10, 2018

Autonomous vehicles and the city: The urgent need for human- and health-centric policies

Rather than allow for an “evolutionary” adaptation to AVs, we must set policies that frame and incentivize a quicker “revolutionary” transition that is driven by cities, not by auto and tech companies.

Urban Planning | Jul 6, 2018

This is Studio Gang's first design project in Canada

The building’s hexagonal façade will provide passive solar heating and cooling.

Urban Planning | Jun 18, 2018

In the battle of suburbs vs. cities, could both be winning?

Five years ago, experts were predicting continued urban rebound and suburban decline. What really happened?

Architects | May 3, 2018

Designing innovative solutions for chronic homelessness

What’s stopping us from creating more Permanent Supportive Housing?

Urban Planning | Mar 14, 2018

Zaha Hadid Architects selected to design Aljada’s Central Hub

The hub will be the centerpiece of ARADA’s masterplan in Sharjah, UAE.