The world’s forests absorb an estimated 16 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, or about double the 8.1 billion metric tons of CO2 that forests emit each year, according to research published earlier this year by Nature Climate Change.

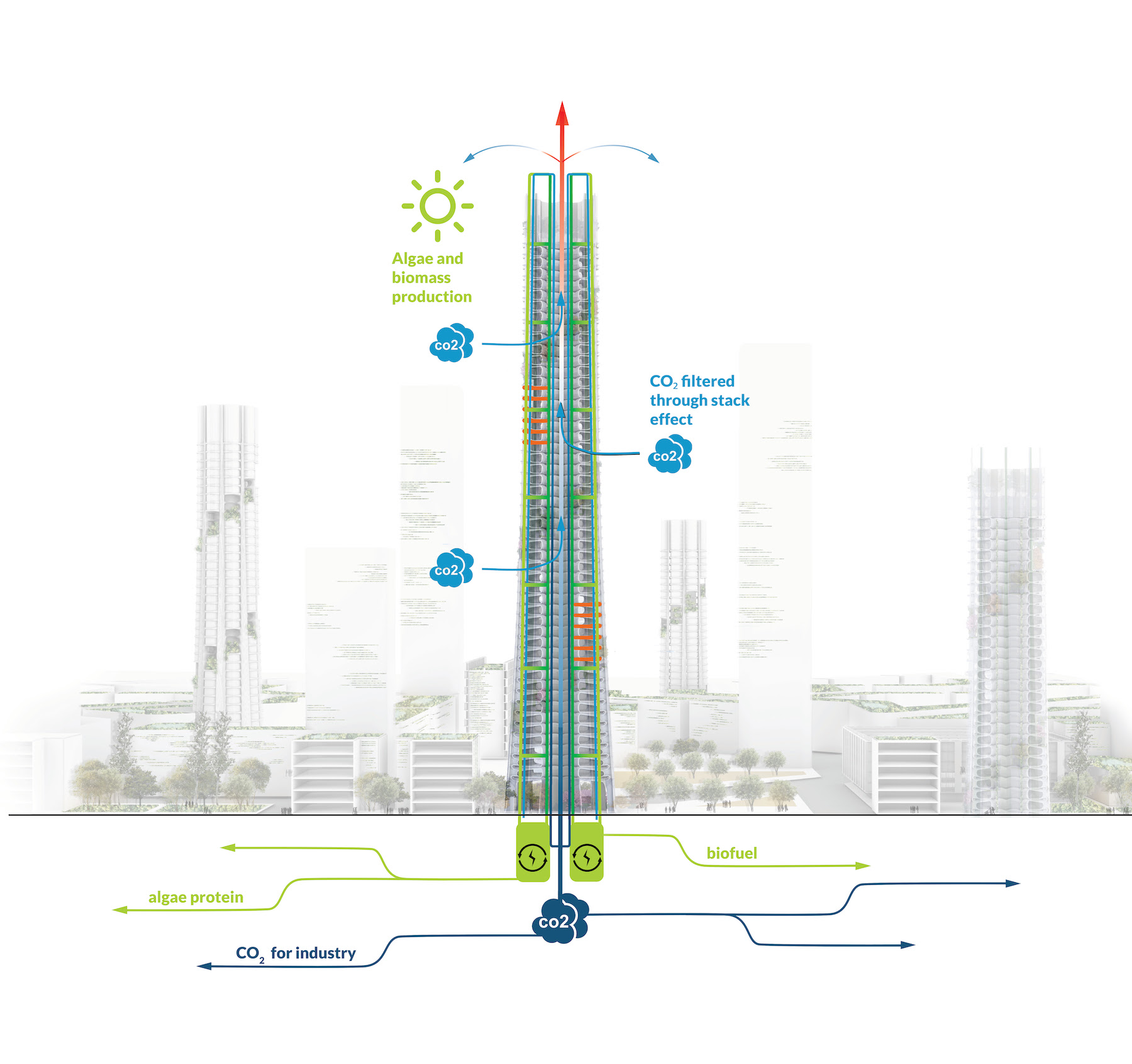

Could buildings—which generate, directly or indirectly, nearly two-fifths of CO2 emissions—act like trees to capture and absorb carbon and keep the air pure? The architecture, engineering, and urban planning firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill envisions that provocative suggestion in a concept it calls Urban Sequoia, which SOM presented during COP26, the 2021 UNN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

SOM pitched its concept at a time when urban population growth rates are dictating the need for an estimated additional 2.48 trillion sf of new buildings by 2060.

How would buildings absorb more carbon than they leak out? By designing and building them specifically to sequester emissions, says Chris Cooper, an SOM Partner. Kent Jackson, another SOM Partner who presented Urban Sequoia at COP26, adds that this concept could be applied and adapted for any metro area in the world, and to all sizes and types of buildings.

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE MATERIALS

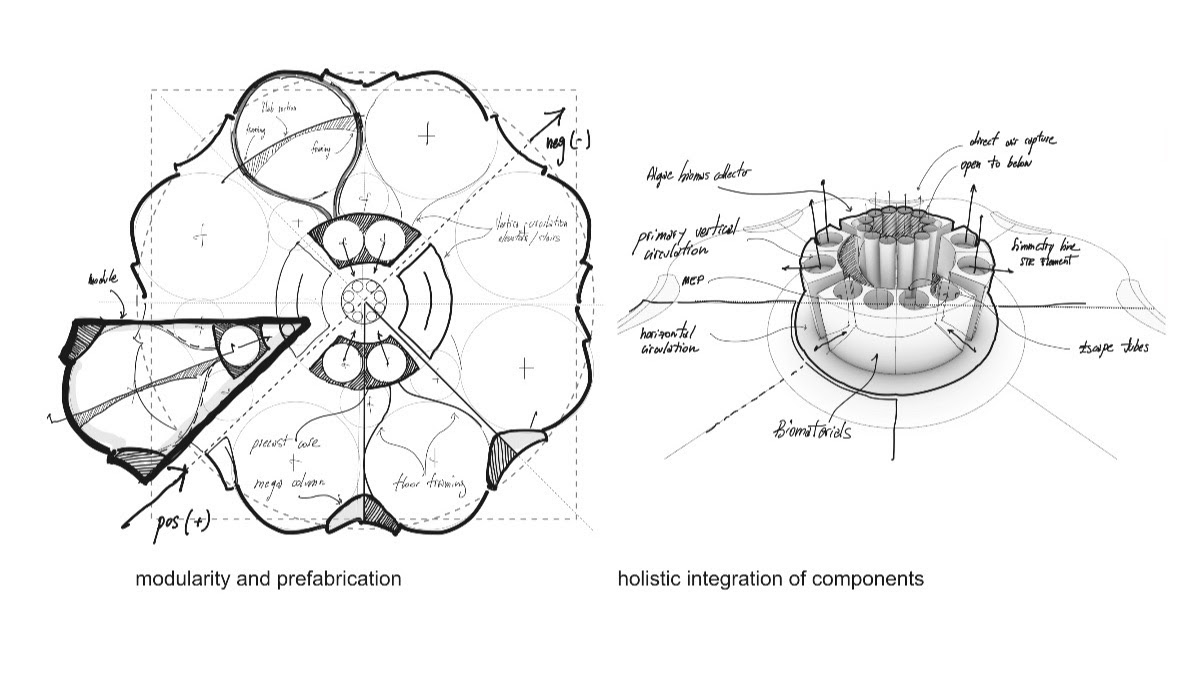

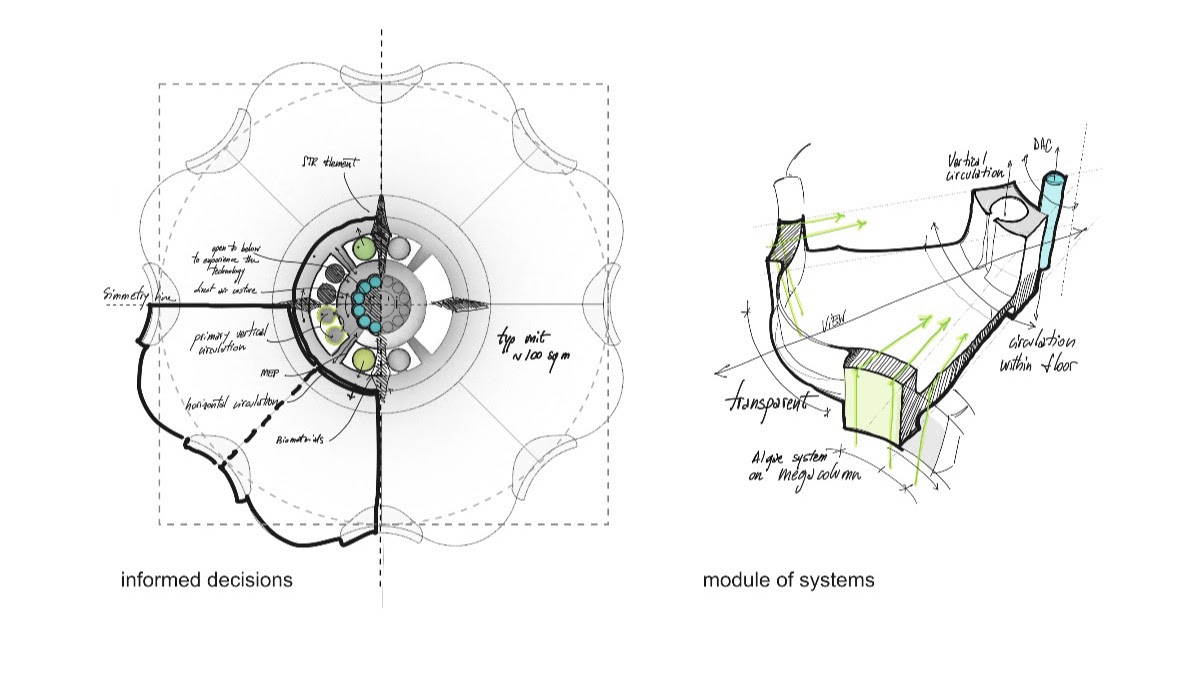

Urban Sequoia is an amalgam of the latest thinking about sustainable design coupled with emerging technologies. Carbon reductions can be achieved, SOM posits, by “holistically” optimizing building design, minimizing materials, and integrating biomaterials and advanced biomass.

To illustrate its concept, SOM’s prototype design is a high-rise building that, theoretically, could sequester up to 1,000 tons of carbon annually, or the absorption equivalent of 48,500 trees. The right combination of nature-based or environmentally friendlier materials—that might include hempcrete, bio-brick, timber, and so forth—could reduce the carbon impact of construction by anywhere from 50 to 95 percent compared to buildings made primarily with steel and concrete.

Over a 60-year lifespan, this prototype building would absorb up to 400 percent more CO2 than it would have emitted during construction, states SOM (which is a little vague about what “industrial applications” the captured carbon would be used for). And the use of bio-materials could turn the building into a biofuel source that would bring the building’s operations beyond net zero.

The goal, in essence, is to turn cities into carbon sinks. SOM contends that if every city around the world built Urban Sequoias, the built environment could remove up to 1.6 billion tons of carbon from the air every year. Such a strategy might also include converting urban hardscapes into gardens, designing intense carbon-absorbing landscapes, and retrofitting streets with additional carbon-capturing technology, former grey infrastructure can sequester up to 120 tons of carbon per square kilometer (0.38 miles). When replicating these strategies in parks and other greenspaces, up to 300 tons per square kilometer of carbon could be saved annually.

The goal, in essence, is to turn cities into carbon sinks. SOM contends that if every city around the world built Urban Sequoias, the built environment could remove up to 1.6 billion tons of carbon from the air every year. Such a strategy might also include converting urban hardscapes into gardens, designing intense carbon-absorbing landscapes, and retrofitting streets with additional carbon-capturing technology, former grey infrastructure can sequester up to 120 tons of carbon per square kilometer (0.38 miles). When replicating these strategies in parks and other greenspaces, up to 300 tons per square kilometer of carbon could be saved annually.

Related Stories

Urban Planning | Feb 26, 2018

A new way to approach community involvement for brownfield projects

A new community engagement program works with young adults to help the future of the neighborhood and get others involved.

Urban Planning | Feb 23, 2018

Paris car ban along the river Seine deemed illegal

Mayor Anne Hidalgo has appealed the decision.

Urban Planning | Feb 21, 2018

Leading communities in the Second Machine Age

What exactly is the Second Machine Age? The name refers to a book by MIT researchers Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee.

Urban Planning | Feb 14, 2018

6 urban design trends to watch in 2018

2017 saw the continuation of the evolution of expectations on the part of consumers, developers, office workers, and cities.

Urban Planning | Feb 12, 2018

Stormwater as an asset on urban campuses

While there is no single silver bullet to reverse the effects of climate change, designers can help to plan ahead for handling more water in our cities by working with private and public land-holders who promote more sustainable design and development.

Urban Planning | Jan 24, 2018

Vision Zero comes to Austin: An outside perspective

Aside from the roads being wider and the lack of infrastructure for bikes and pedestrians, there seemed to be some deeper unpredictability in the movement of people, vehicles, bikes, and buses.

Urban Planning | Jan 10, 2018

Keys to the city: Urban planning and our climate future

Corporate interests large and small are already focused on what the impact of climate change means to their business.

Urban Planning | Jan 2, 2018

The ethics of urbanization

While we focus on designing organized and supportive architecture, much of urbanization is created through informal settlements.

Urban Planning | Dec 5, 2017

A call for urban intensification

Rather than focus on urban “densification" perhaps we should consider urban “intensification.”

Urban Planning | Dec 4, 2017

Sports ‘districts’ are popping up all over America

In downtown Minneapolis, the city’s decision about where to build the new U.S. Bank Stadium coincided with an adjacent five-block redevelopment project.