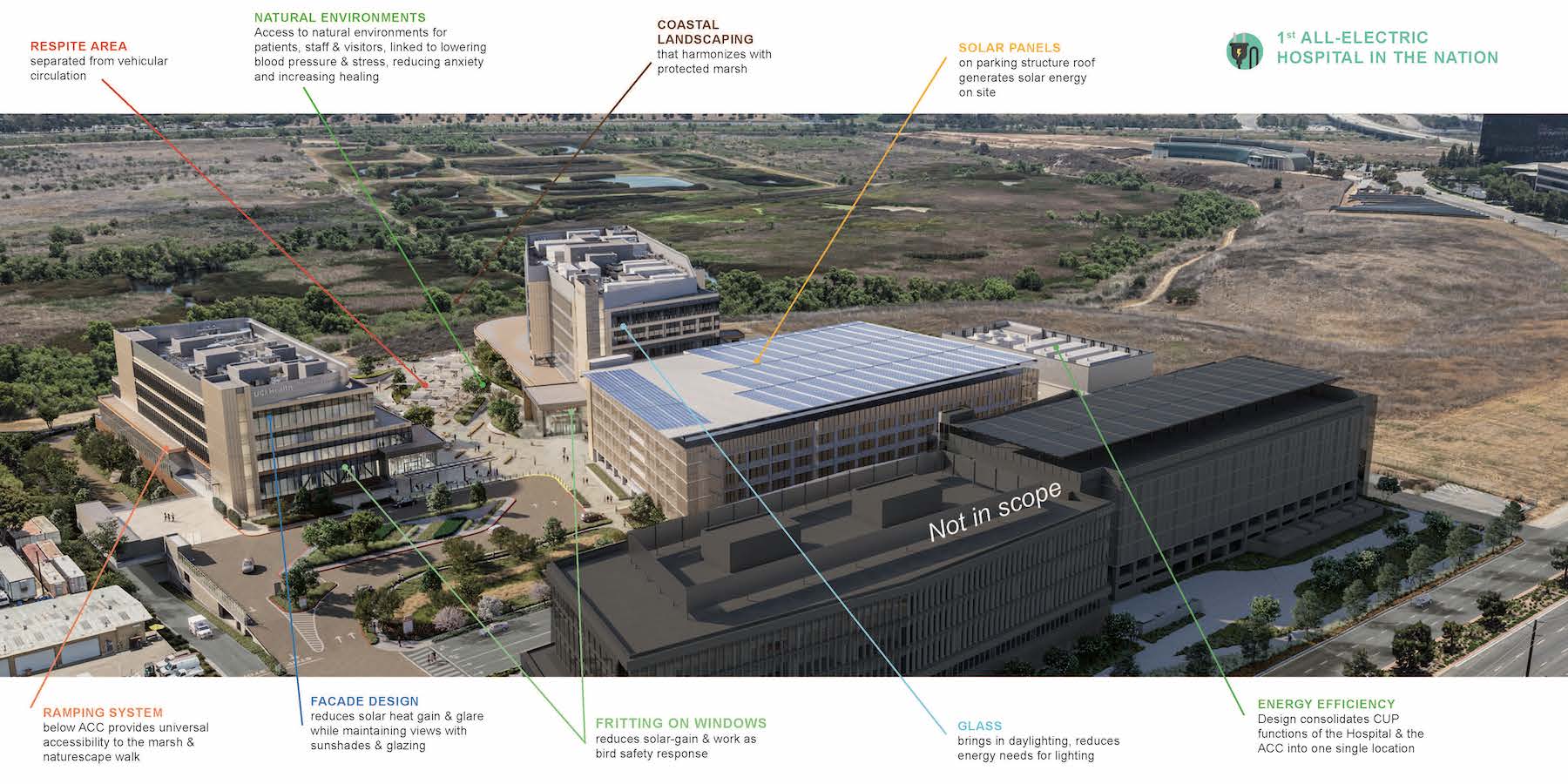

The University of California at Irvine (UCI) has a track record for sustainability. It recently received LEED Platinum certification for its 23rd campus building. Its under-construction UCI Medical Center is designed, positioned, and built to preserve the nearby San Joaquin Marsh Reserve, to reduce the facility’s solar gain by 85%, and to be the first medical center in the country to operate on an all-electric central plant.

The University of California’s system favors sustainable solutions, including its requirement that new construction be all-electric. Instead of filing for a waiver, UCI determined that it could meet that requirement “at only a modest premium,” says Brian Pratt, UCI Campus Architect and Associate Vice Chancellor. (The premium would be around $2.5 million on a project whose construction cost is $770 million and all-in cost will be over $1 billion.)

UCI Medical Center will consist of a four-story, 357,000-sf hospital with 144 beds, operating rooms, 20 Emergency Department beds, and 16 acute observation beds; a 223,000-sf Comprehensive Cancer and Ambulatory Care Center with 36 exam rooms, outpatient surgery, labs, and a pharmacy; a 35,000-sf central plant; and a parking structure with 1,340 spaces.

The parking structure was completed last year, and the outpatient building and central plant are scheduled for completion next year. The hospital should be done in 2025. To meet California and national code requirements, the power system will be backed up by diesel fuel generators (see Editor's note below).

Electrification without compromise

The decision to go all-electric was made early in the design process, recalls Khristina Stone, Preconstruction Manager for the GC Hensel Phelps, which with CO Architects leads the Progressive Design-Build team on this project. Nick Spady, Hensel Phelps’ Operations Manager, says that installing the buildings’ electrical infrastructure and emergency generators pose the greatest challenges in an all-electric environment.

The bridging documents actually described an electric heating system that allowed for the use of natural gas for steam. But ultimately the design-build team and the university decided to dispense with steam boilers altogether, says Roger Carter, CEO and Senior Principal of tk1sc, the project’s MEP engineer.

Carter notes that state codes now require hospital rooms to have constant air volume, which can impact the heating system’s’ load. An all-electric system will allow UCI’s hospital to leverage the central plant’s heat-recovery chillers to manage the building’s energy performance. Indeed, going all-electric is not expected to compromise the medical center’s operations, whose universal design allows for all patient rooms to be converted to intensive care units.

UCI Medical Center is being built under a Progressive Design-Build contract, which Pratt says has been the university’s bid-out preference for decades. He notes that hospital projects are complicated with many stakeholders, and a Progressive Design-Build agreement “allows for expert feedback earlier in the project.”

He notes, parenthetically, that prior to construction UCI had worked with the architect HOK for a year on the medical center’s programming. “This put up guardrails on the project, but with enough room for flexibility.” Gina Chang, CO Architects’ Principal and Healthcare Team Lead, says there was also a program alignment period, during which the team could receive comment and suggestions from UCI and the hospital’s users.

“The bridging documents weren’t overly heavy, so the contract set up a more positive relationship [with UCI] for flexibility and creativity,” says Stone.

The rest of the Progressive Design-Build team includes Degenkolb (SE), Stantec (CE), Ridge Landscape Architects (LA), Newson Brown Acoustics (acoustical engineer), and Colin Gordon Associates (acoustical vibration).

Indoor and outdoor wellness

Aside from its electrification, UCI Medical Center features other sustainable elements. For example, the choice of brace framing, which Pratt says was “rooted in resilience,” reduces the project’s measurable embodied carbon by 20 percent. CO’s Chang further explains: “We implemented the lightest structural system possible (BRBF buckling restrained braced frame) to reduce the embodied carbon footprint. Though we sought for carbon reduction also with the concrete design, the site had high levels of methane and other greenhouse gasses that needed to be contained, so a larger, mat footing was utilized to mitigate that problem.”

After conducting several frit and shading studies, the design team optimized the building’s envelope to reduce its solar gain by 85 percent, and to minimize bird strikes.

The medical center will also tap into the city of Irvine’s robust recycled water infrastructure.

Chang says the marsh—which is managed by UCI biologists—drove the massing and position of the buildings. “We took seriously being a good neighbor to the marsh,” adds Pratt. The construction site includes a turtle fence. And the biologists said that runoff from the site was fine as long as it was treated.

Like most healthcare facilities, UCI Medical Center is placing a premium on wellness. It has multiple areas for gathering outdoors, including walkable pathways and so-called healing gardens that offer views of the landscaping. (The outside plaza between the hospital and outpatient buildings brushes up against the edge of the marsh.)

“The landscape design and plant palette matter,” says Pratt. “And the marsh in the differentiator.” Indoors are numerous terraces, and other places of respite that include “lavender” rooms where staff members under stress can retreat.

________

Editor's note: After this story was posted, Ray Swartz, an engineer and Senior Principal with tk1sc, the project's MEP engineer, responded to a reader's question about the Medical Center's backup power source in the event of an electrical outage:

Swartz said that California's Department of Health Care Access and Information enforces a minimum of 72 hours of fuel storage for a new NPC-5 building, not the 96 hours required by NFPA 110. However, NFPA 110 requires the main fuel tank(s) to have a minimum capacity of at least 133 percent of the quantity needed by CEC 700.12 (B) (2) Exception 1 or 2. Therefore, for NPC-5 buildings, the minimum capacity requirement is 133 percent of the 72-hour fuel supply, equating to 96 hours.

The UCI Medical Center project includes four 3,000-kW generators operating in parallel. The capacity is adequate to service the campus in a 100 percent business-as-usual format. The generators are diesel fuel type, and the campus has an underground fuel storage capacity of 65,000 gallons. If, in an emergency, refueling the tanks is feasible, the campus could operate continuously under generator power.

Related Stories

Giants 400 | Aug 6, 2015

HEALTHCARE AEC GIANTS: Hospital and medical office construction facing a slow but steady recovery

Construction of hospitals and medical offices is expected to shake off its lethargy in 2015 and recover modestly over the next several years, according to BD+C's 2015 Giants 300 report.

Contractors | Jul 29, 2015

Consensus Construction Forecast: Double-digit growth expected for commercial sector in 2015, 2016

Despite the adverse weather conditions that curtailed design and construction activity in the first quarter of the year, the overall construction market has performed extremely well to date, according to AIA's latest Consensus Construction Forecast.

Healthcare Facilities | Jul 23, 2015

David Adjaye unveils design for pediatric cancer treatment center in Rwanda

The metallic, geometric façade is based on the region’s traditional Imigongo art.

Healthcare Facilities | Jul 22, 2015

Best of healthcare design: 8 projects win AIA National Healthcare Design Awards

Montalba Architects' prototype mobile dental unit and Westlake Reed Leskosky's modern addition to the Cleveland Clinic Brunswick Family Health Center highlight the winning projects.

Healthcare Facilities | Jul 8, 2015

From Subway to Walgreens, healthcare campuses embrace retail chains in the name of patient convenience

Most retail in healthcare discussions today are focused on integrating ambulatory care into traditional retail settings. Another trend that is not as well noted is the migration of retailers onto acute care campuses, writes CBRE Healthcare's Craig Beam.

Healthcare Facilities | Jul 6, 2015

The main noisemakers in healthcare facilities: behavior and technology

Over the past few decades, numerous research studies have concluded that noise in hospitals can have a deleterious effect on patient care and recovery.

University Buildings | Jun 29, 2015

Ensuring today’s medical education facilities fit tomorrow’s healthcare

Through thought-leading design, medical schools have the unique opportunity to meet the needs of today’s medical students and more fully prepare them for their future healthcare careers. Perkins+Will’s Heidi Costello offers five key design factors to improve and influence medical education.

Sponsored | Healthcare Facilities | Jun 23, 2015

Texas eye surgery center captures attention in commercial neighborhood

The team wanted to build an eye surgery center in an already established area but provide something clean and fresh compared to neighboring buildings.

Healthcare Facilities | Jun 16, 2015

Heatherwick’s design for cancer center branch has ‘healing power’

The architect describes it as “a collection of stepped planter elements”

Healthcare Facilities | May 27, 2015

Roadmap for creating an effective sustainability program in healthcare environments

With a constant drive for operational efficiencies and reduction of costs under an outcome-based healthcare environment, there are increasing pressures to ensure that sustainability initiatives are not only cost effective, but socially and environmentally responsible. CBRE's Dyann Hamilton offers tips on establishing a strong program.